Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh: Impressions of Landscape at the Van Gogh

Museum to 29 Jan 2017

|

| Charles-François Daubigny: Sunset near Villerville, 1874 |

This is the third iteration of an exhibition which

has arrived from Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati via the Scottish National

Gallery in Edinburgh. It’s easy enough to imagine the conversations as it

was planned. Who’s going to turn up to see why the apparently conventional

landscapes of Charles-François Daubigny (1817-78), a member

of the Barbizon school who was rich and famous in the nineteenth century but

little-recognised now, should return to the artistic summit? Not many: we’d

better include some other artists – perhaps the most bankable possible. How about the title? ‘Daubigny in his Times’? I guess not. ‘Daubigny, Monet, Van Gogh: Impressions of

Landscape’? That will

do nicely…

Yet, even if there were any such opportunism, it doesn’t

undermine this show in the slightest. First, because Daubigny is a figure worth

reviving. Second, because the connections made are elegantly demonstrated and

far from spurious.

|

| Daubigny: Banks of the Oise, 1859 |

Looking at a typical Daubigny from when he first found

success in the 1850’s, it is hard to see why he proved a divisive figure, with

factions claiming him both as the ultimate realist and as radical slipshod who failed to finish his paintings properly – so

that he gave, it was said as early as 1864, only ‘an

impression’ of the view. To our eyes, Daubigny’s grounding in the actuality of

nature is as clear as the artfulness with which he leaves his technique

visible: pallet knife on clouds, a blurred drag of reflections, various precise

abbreviations which keep the surface lively and the viewer’s eye active in

moving between what is depicted and how.

And though he remained true to the principle of painting only what he

saw, it’s apparent that he didn’t paint it all, editing for composition (as

well as to exclude most aspects of modern life). Moreover, Daubigny’s

preference for a panoramic format twice as long as high – such as the 88 x

182cm Banks of the Oise, 1859 - adds drama. The 38 Daubigny paintings in

Amsterdam include several such, for this is itself a highly edited account of Daubigny.

He produced thousands of paintings over a prolific forty year career, many of

them on the small scale suitable for sale to collectors, often painted at the more conservative end of his

style to suit the market. What we see are mainly the showpieces Daubigny

produced with the Salon in mind, hoping for state and institutional sales.

The case to be made here, then, is that Daubigny deserves to

be considered alongside Courbet, Corot and Millet – as, indeed, he was at the

time. Daubigny recognised kindred spirits and embraced the new artists: he was

an influential member of the jury which selected several the next

generation for the 1866 Salon before

Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, 1872,

ushered in ‘impressionism’ as a recognised movement. His example mattered

to the impressionists, and now their ideas began to inform his work, which gets

brighter and looser, though always within the bounds of classically balanced composition.

The exhibition aligns paintings most effectively to demonstrate the to and fro

of influence.

|

| Daubigny, Cliffs at Villerville-sur-Mer, 1872 |

On the ground floor, we see Monet (and also Pissarro)

through the lenses of their awareness of Daubigny. There is read-across from the

older artist in terms of subject matter and approach as their views of the same

places – notably Villerville on the Normandy costs - are hung side by side. Daubigny

was also a practical forerunner: Monet is famous for using a studio boat to

enable him to paint comfortably in plein

air and depict the riverscape as from mid-stream.

|

| Monet: Monet's studio-boat, 1874 |

Daubigny was there earlier, one

of the first to paint outside (exploiting the new availability of paint in

tubes) and using a bigger boat – its dimensions are reconstructed in the exhibition

– with a similar idea.

|

| Daubigny: Apple Blossoms, 1873 |

|

| Monet: Spring (Fruit Trees in Bloom), 1873 |

|

| van Gogh: The white orchard, 1888 |

Later the influence was mutual. Daubigny was first with the subject of orchards in blossom, which he painted regularly from 1857. His take is juxtaposed with Monet and Van Gogh’s, both of which push the floral intensity quite a bit further. Another telling comparison is of fields of poppies, in which an 1874 Daubigny gives Monet a fair run for his money. Daubigny’s late style could be bold and broad, focused on the emotional impact of a landscape and on meteorological variation rather than the precise delineation of its forms.

|

| Daubigny: Moonrise at Auvers, 1877 |

In the words of the great champion of the impressionists, Zola, the ‘limpid grandeur’ of Moonrise at Auvers, 1877,

is ‘far from the classical style, which lacks anything personal’.

|

van Gogh: Wheatfield under Thunderclouds, 1890

|

Daubigny died before Van Gogh became an artist, so that

influence operates only one way. Van Gogh’s letters mention his

admiration of Daubigny, he adopted his subjects, and he spent the last days of

his life in Auvers. Van Gogh moved there for Dr Gachet’s care, but the fact that

Daubigny’s house was in the town was a bonus which led to paintings of his

garden and – the curators argue – Van Gogh’s adoption of ta wide horizontal format

for his last paintings, such Crows over a Cornfield, 1890. There’s a clear link as the show unfolds

between the three principals: all have a passion for nature, and seek to

express it, the difference being the degree to which they allow their

engagement to come to the surface: from Daubigny to Monet to Van Gogh

represents an escalation of intensity, but a similarity of intent.

To keep it in perspective: Daubigny isn’t going to blow you

away from across the room the way Monet and Van Gogh can. And it would be going

too far to present him as a proto-impressionist in the 1850’s, because his

theoretical framework was different: Daubigny wasn’t painting the sensation of

light as his primary reality, just painting objects in an undogmatic way.

|

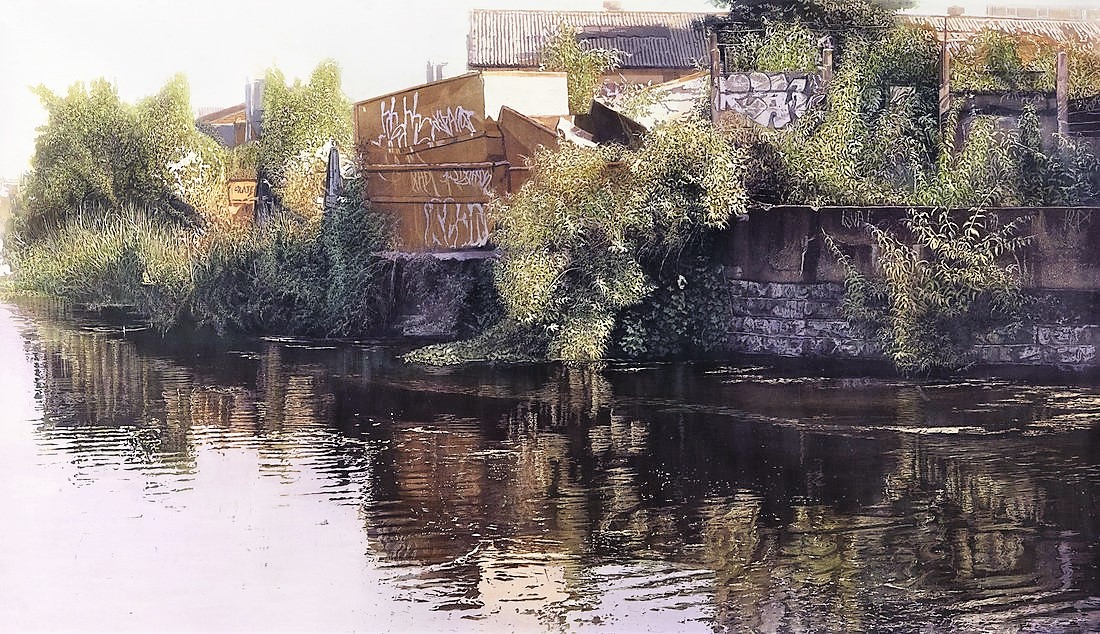

| Installation shot - ground floor |

The Amsterdam leg comes with three features additional to

its previous presentations. First, unsurprisingly, more paintings by Van Gogh.

Second, a gimmicky-sounding exhibition design which is actually implemented sensitively

enough not to intrude: there are wall-sized videos of contemporary river

scenes; the ground floor walls are painted in gloss and matt blues which

suggest a waterline such that the paintings – as well as the boat - could be

afloat; and the upstairs floor walls are coloured to suggest a sunset, in line

with another subject covered by all three artists. Third, there’s a bonus

room bringing together the Van Gogh Museum’s choice of French landscape

drawings from its extensive collection, putting the famous three in a broader

context.

Overall, then, in terms of the work shown and the story

told, this is a very fine exhibition. If

you haven’t seen it elsewhere it would certainly make a good focus for a trip

to Amsterdam. In which case, you might ask, what other art might I see there

now?

Up Now In Amsterdam

Two days is enough to see all the contemporary art in

Amsterdam without feeling rushed: that’s maybe 20 commercial galleries and 10

institutions, and, even without that narrow range, patterns began to emerge (and quality was good - I've listed close to half of what I saw below):

|

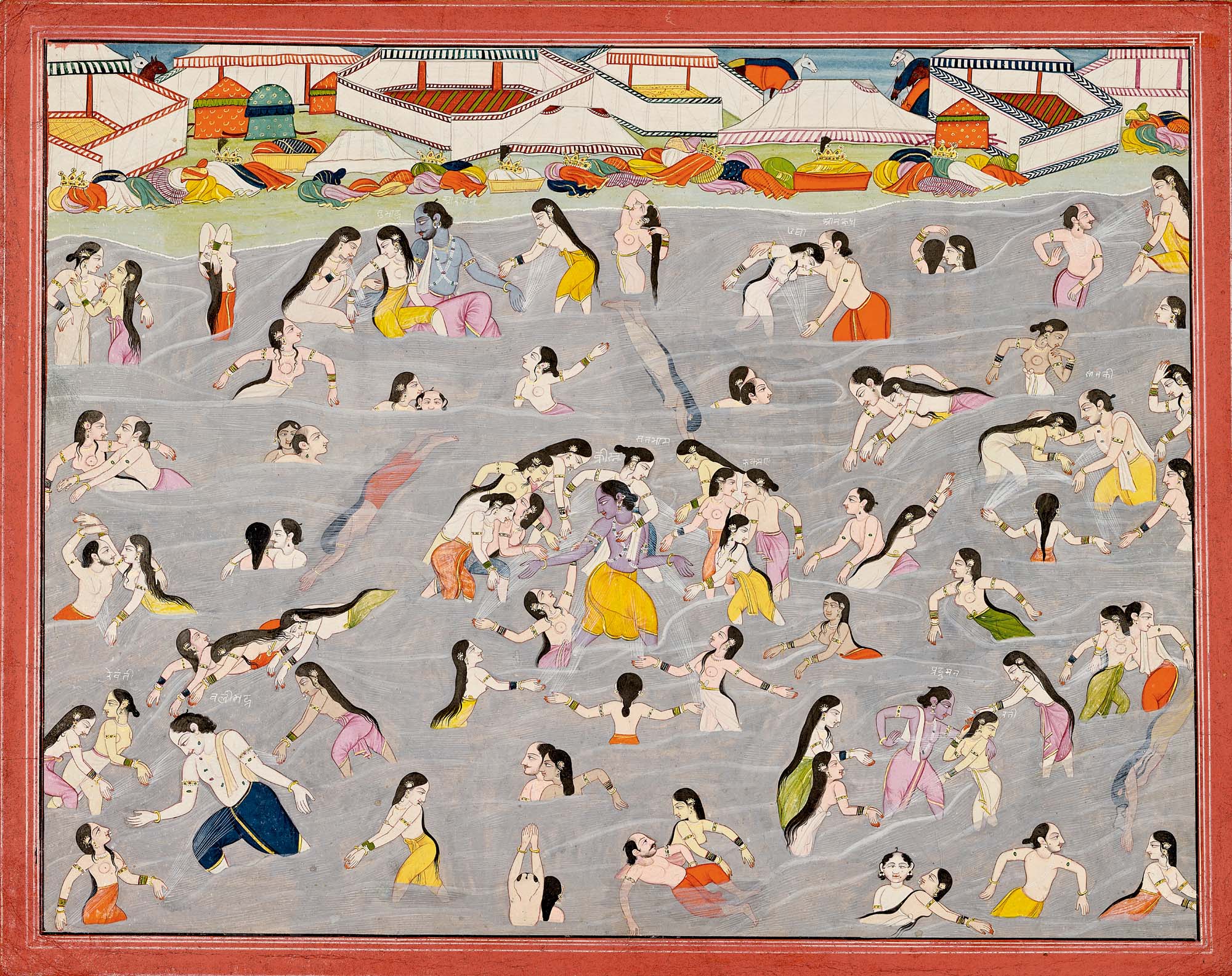

Still from Melanie Bonajo: Night Soil – Economy of Love, 2016 - 23 mins

|

A strand of Dutch post-feminist surrealism could be posited

from three fascinating shows: Scarlett Hooft Graafland at the beautiful classic

townhouse of Huis Marseille Museum for Photography; the three semi-documentary films

of Melanie Bonajo’s ‘Night Soil’ sequence at Foam, which look at modern

alternative rituals around drugs, sex and food (she rather dominated Foam’s

headliner, AI Wei Wei); and Femmy Otten’s fantastical tales of the sea at Fons

Welters. Those three together would make for an intriguing and popular show at,

say, Camden Arts Centre…

|

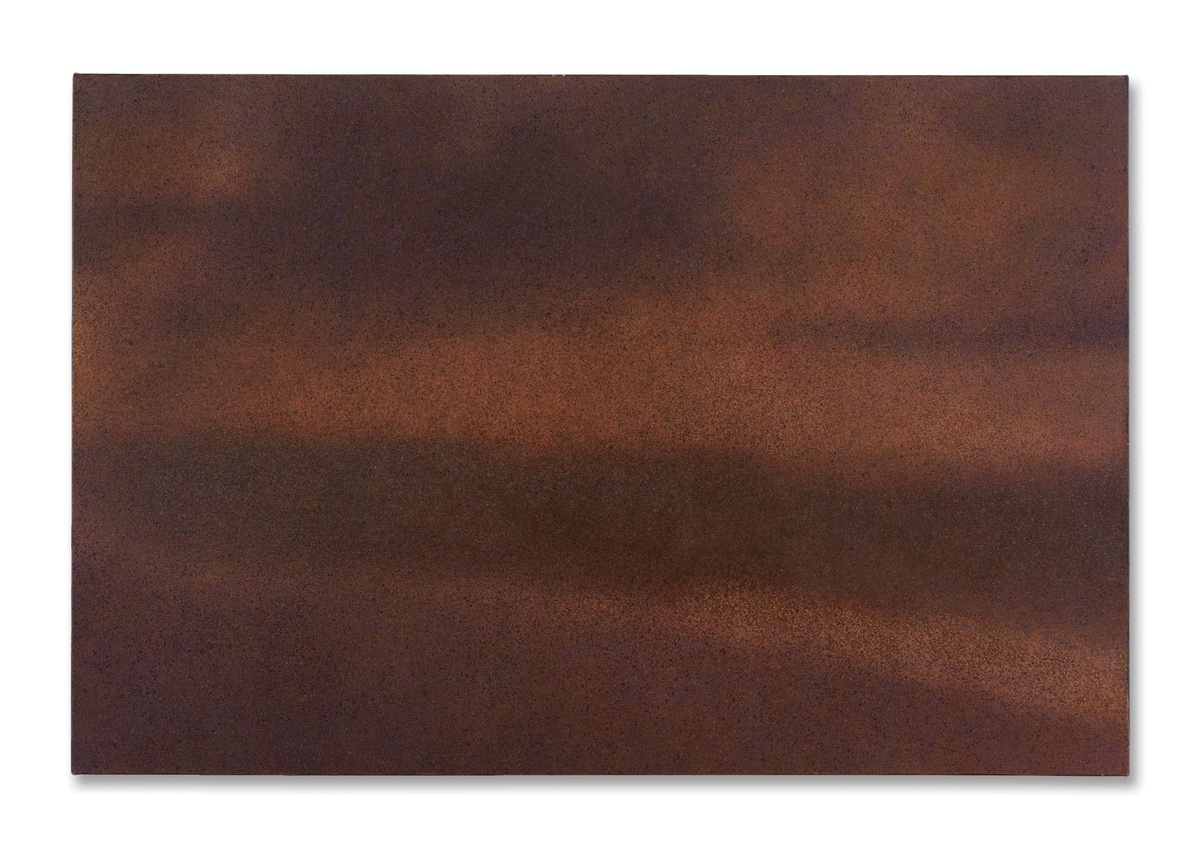

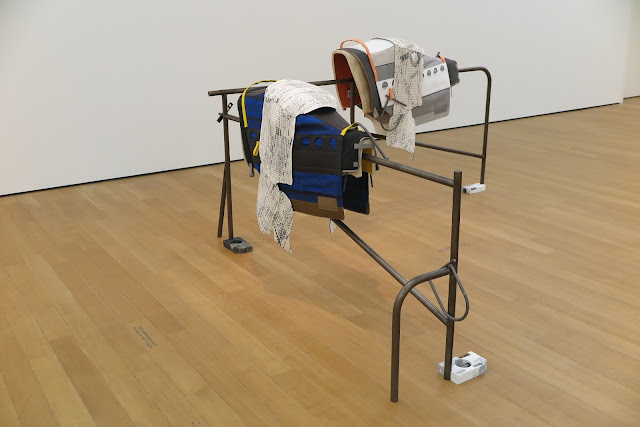

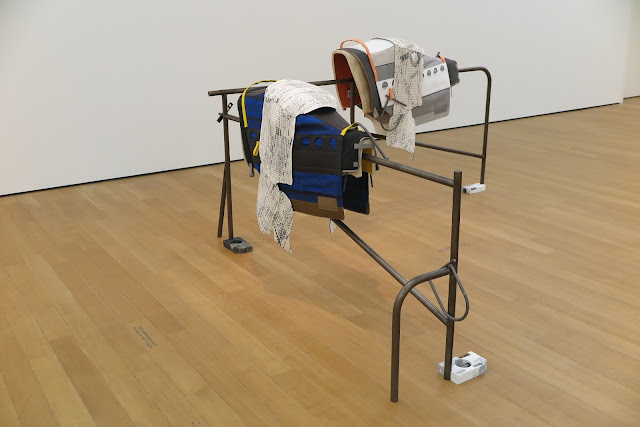

| Magali Reus: Toucan-brow, 2016 |

London-based Dutch artist Magali Reus had a wonderful room of new work at the Stedelijk (where the big show was of Jean Tinguely). I wasn’t so impressed by Hanae Wilke at Ornis A, apart from how close she was to being the better known Hannah Wilke. Her aesthetic seems to relate to Reus’s, though - then I noticed she, too, is from The Hague…

|

| Maria Banas: The Planet O, 2016 |

The Tinguely show was also upstaged. On the one hand it went through the motions well enough – on the other, there was hardly any actual mechanical motion, which is his essence. That left the coast clear for a most engaging dry-ice speech-bubble poetry machine by Maria Barnas at Annet Gelink, which set off its effects as it meditated on the possible materiality of the letter ‘o’.

|

| Gabriel Lester: still from Murmur |

De Appel had riotously imaginative show by Gabriel Lester

and collaborators, albeit ‘Unresolved’ by both title and nature (deliberately

so, to reflect De Appel’s own parlous state). The big hit for me was his film

‘Murmur’, in which a string quartet plays behind the wall of a gallery as they argue cattily among themselves about the rights and wrings of the art world.

|

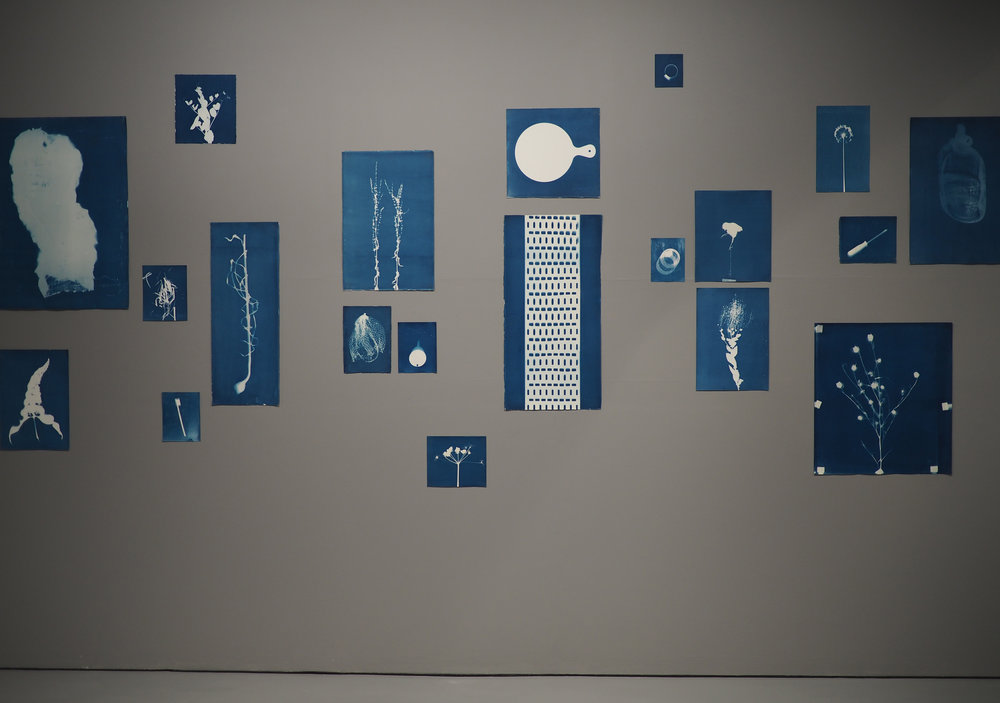

| Eva Stenram installation shot |

Two other shows, both in the fresh and breezy northern part

of Amsterdam, examined particular languages with conviction. Eva Stenram is

known for repurposing vintage glamour photographs, and at the Ravestijn Gallery

(which is in the office of a creative agency) she showed them with textile

installations taken from the textiles in the images – even down to the effect

of foreshortening – so that the conditions of image reception were complicated

and foregrounded. The film museum EYE has impressive exhibition spaces, which

did justice to what may remain the definitive examination of the endgame of

celluloid as a photo-sculptural practice.

|

| Levi van Veluw installation view |

Stigter Van Doesburg provided a nice complement to the Van Gogh Museum: Saskia Olde Wolbers’ film voiced by the house in which Vincent lived in Brixton in 1873-74, originating from Artangel in London. It was good to see the Amsterdam iteration of Levi van

Veluw’s outstanding The Monolith – closely related to his London show (at Rosenfeld Porcini

to 26 Nov) in overall impact, but with two immersive environments, one of them

watery. Both derive from his mother of all installations at Maastrict, which you can get a feel for at http://levivanveluw.com/work/relativity-matter-film-0.

Another prior favourite was at Ellen de Brujna Projects, and watching

it in better conditions than before leads me to emphasise that if you get

the chance to watch Erkka Nissinen’s animation What Is Community?, you should take it!

|

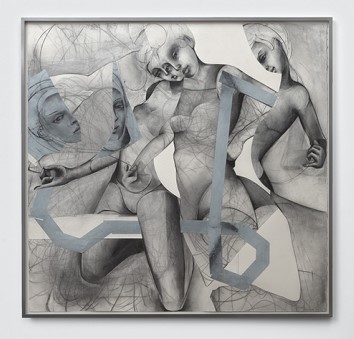

| Lenz Geerk: Lotion, 2016 |

That leaves only a couple of shows I liked which

didn’t really fit with anthing else: Gerhardt Hoofland had German painter Lenz

Geerk’s brilliant use of looking at the soles of one’s feet as ‘a metaphor for

the operation of self-reflection and self-profling’ by way of thick paintings

on wool of people contortedly attempting just that, shown (a little unnecessarily) with foot lotion dispenser and towel. And young Slovak Aljaz

Celarc set up a self-sustaining world of ice at DSC & H Gallery in the

complex environmentally resonant ‘A Stagmite for Sisyphus’, which certainly

took my 'best show title' title.