Richard

Diebenkorn at the Royal Academy (to 7 June): Six Painters on a Painters’ Painter

With Michael Stubbs, DJ Simpson, Katrina Blannin, Claudia Carr, Christina Niederberger and Dolly Thompsett

AN EDITED VERSION OF THIS DISCUSSION APPEARS AT THE EXCELLENT AMERICAN ONLINE MAGAZINE ARTCRITICAL AT

www.artcritical.com/2015/05/04/paul-carey-kent-richard-diebenkorn/

With Michael Stubbs, DJ Simpson, Katrina Blannin, Claudia Carr, Christina Niederberger and Dolly Thompsett

AN EDITED VERSION OF THIS DISCUSSION APPEARS AT THE EXCELLENT AMERICAN ONLINE MAGAZINE ARTCRITICAL AT

www.artcritical.com/2015/05/04/paul-carey-kent-richard-diebenkorn/

|

| Ocean Park #27, 1970 |

The Royal Academy's Richard Diebenkorn show operates (to 7 June) on the basis that if he is known at all in Britain - and the publicity for and reviews of the show tended to assume that he isn’t - then it’s for his late Ocean Park series (all Diebenkorn’s serial work is identified by the studio in which it was produced). Accordingly, curator Sarah C Bancroft sets out to challenge that narrow view by stressing the historical and geographic narrative of how Diebenkorn (1922-93) moved from the early abstract phase in room 1 (Albuquerque, New Mexico and Urbana, Illinois 1950-56) to a surprising figurative turn in room 2 (Berkeley, near San Francisco, 1956-66) to the Ocean Park paintings in room 3 (Santa Monica, on the Californian cost, 1967-88). The show has 20, 25 and 15 works respectively from those three periods, including drawings from each and 5 of the 145 large paintings in the Ocean Park series.

|

| From left: Claudia Carr, Katrina Blannin, Michael Stubbs, Christina Niederberger, Dolly Thompsett and DJ Simpson outside the RA - see below for examples of their work |

Ahead of the Royal Academy’s efforts, then,

Diebenkorn’s British reputation lay mainly with painters rather than the

general public, so it made sense to take six well established painters to

the show and seek their opinions on it. They split pretty much 50-50,

with Michael Stubbs, DJ Simpson and Katrina

Blannin persuaded of the importance of at least the Santa Monica

years, but Claudia Carr, Christina Niederberger and Dolly

Thompsett finding little to praise in Diebenkorn’s whole oeuvre. The

artists tackled several questions. Was Diebenkorn shown to advantage? What were

the continuities between his three phases? Is the pre-Santa Monica work

successful in its own right? And just how good is the late work?

|

| Berkely #57, 1955 |

There was some criticism of the hang. Simpson felt

that the crowded early rooms left far too little space between paintings. Carr

agreed, finding that the experience became ‘colourful, rather than about

colour’ – as it wasn't optically possible to isolate the colour relationships within

a given painting from those of its neighbouring paintings. The third room did

give somewhat more space to the work, but the Sackler Rooms on the Royal

Academy's third floor have no natural light, and everyone felt that Ocean Park

paintings would have benefited greatly from that: ‘the artificial lighting

overemphasises the yellow tones’, said Blannin. The consensus was that these

paintings deserved to be hung in one of the RA’s larger galleries. Would it,

failing that, have been better to drop 1950-66 entirely, and spread the late

work only around all three rooms to ensure a spacious presentation of big

paintings concerned with spaciousness? Blannin and Stubbs tended that way…

|

| Urbana # 6, 1953 |

Looking at the first room, Stubbs emphasised the historical context: the paintings were ‘typical of the early fifties in developing a cubist space into more fluid forms which value spontaneous gestures, and which simultaneously construct and contradict the space’. Affinities were noted with English painters in the fifties: Heron, Lanyon, and Hitchens. Niederberger, too, felt that Diebenkorn's paintings are very much of their time, making them harder to access today in a way which she saw as problematic, as 'they lack, say, Mondrian's aspect of universal/eternal validity'. That stems, she believed, from 'Diebenkorn's abstract marks and choices of colour often appearing arbitrary'. A venerable question arose: how did Diebenkorn know that a work was finished? Stubbs felt little judgement was in evidence: he had tended to 'throw everything at the picture until he decided to throw in the towel as well’. Simpson was more persuaded by Diebenkorn’s instincts. Quoting one-liner summaries of the instinctual decisions involved, he thought he’d judged ‘when there's enough push and not enough pull’, or when he’d achieved ‘the right kind of wrongness’. Simpson liked the oddity in Diebenkorn’s colours, and how certain areas – for example, the purple in Urbana # 6, 1953 - took on the status of objects within the pictorial field. He also liked the variation between dry-looking and comparatively lush application of paint.

|

| Interior with View of Buildings, 1962 |

Diebenkorn never prepared the ground with sketches, to find a solution he was

happy with and could then implement: ‘a premeditated scheme or system is out of

the question’, he said. Rather, all the action can be seen in the paintings.

That means they are heavily layered – albeit the layers are thin, we’re not

talking Auerbach here. The artists agreed that many early works could be read

as aerial landscapes – or sometimes interiors – even though their primary

qualities are abstract. They also agreed that Diebenkorn appeared to operate by

addition only, with some scratching into the surface, but no scraping off of

layers. Indeed, one of Diebenkorn's own rules (from his list of ten Notes

to myself on beginning a painting) was that ‘Mistakes can’t be erased but

they move you from your present position’.

|

| Untitled, 1964 - ink on paper |

I rather liked a group of life drawings,

which Diebenkorn started to produce at mid-fifties Wednesday evening sessions

with his friends David Park and Elmer Bischoff, and which marked the beginning

of his move towards explicit representation. True, the debts to Matisse

are undeniable, but they have a relaxed intimacy, and integrate the figures

convincingly into their architectural settings in a way which links to the

frequent presence of windows in the figurative paintings, and to the

architectonic character of the abstracts to come. Yet the artists didn’t value

these, seeing them as routine implementation of commonly taught approaches –

including the treatment of backgrounds.

In fact, none of the painters rated the middle

period highly, but their reasons varied. There was something of a division

between the sexes – indeed, the men were generally more sympathetic towards

Diebenkorn. Stubbs – poking fun at Baselitz’s absurd views – jokingly suggested

that was because women didn’t understand painting. More relevantly, the

painters whose own practice is most abstract tended to be the most sympathetic.

Simpson and he thought that some of the paintings succeeded, but that they were

too imitative of Matisse, Bonnard, Hockney and Cezanne. Thompsett felt the

diaristic still lives did what they did less well than had William Nicholson.

The doubters complained that Diebenkorn failed to generate any psychological

charge, and that - whilst there were certainly strong abstract aspects present

- they weren’t interesting in this period. Thompsett provided a partial

exception: one of these mid-period paintings – the small landscape Seawall,

1957 – was the only one she really connected to in the whole survey. That

aside, she couldn’t grasp what

he wanted to communicate, what drove him to make work. But the underlying abstract qualities of Seawall did

generate ‘the equivalent of atmospheric movement, which is emphasised by the

airiness of a large green area, readable as grass’. Here, Thompsett felt,

‘Diebenkorn had generated the language of sensation’, whereas elsewhere, she

concluded, ‘he lacks a soul’.

Did Diebenkorn emerge as a strong colourist in the

late work? Carr and Thompsett thought not. Thompsett was unimpressed by their

pastel tendencies, finding them ‘chalky’ and too keen to be

pretty. Seeing Diebenkorn’s ‘structure of horizontals and

verticals with a relatively desaturated colour palette’, Carr said she

‘couldn’t help wanting them to have the kind of rigorousness and sensitivity

that Agnes Martin’s paintings do. She uses colour in a very optically

active way. His intention with colour seems to be entirely descriptive of

place or mood. The ‘mood’ in Martin’s paintings comes about through

a more alchemical process, whereby specific colours are pitched in relation to

each other so that their interaction releases a new energy and, in turn, new potential

emotional states in the viewer’. Blannin, on the other hand, loved the way

she could see that ‘saturated colours have been diluted by milky washes’.

She emerged as the great enthusiast for the late work, admiring Diebenkorn’s

ability to achieve his effects on the reduced scale of cigar box lids as well

as in the seven foot high canvases – with which she said she’d be keen to live,

perhaps the diagonal energies of Ocean Park #27, 1970 and the

aqueous calm of #116, 1979 .

Diebenkorn denied any representational element, but

the Ocean Park series do retain an aerial and window-like feel which reads

across from the earlier abstractions, consistent with their production in a

studio overlooking the sea from a high vantage point. Continuity or not, Stubbs

thought there was justice in the greater fame of the late work in which he felt

Diebenkorn was ‘more confident with the edges of forms and with variations

between soft and hard edges'. If so, this may be what Diebenkorn got out of the

move into and out of figuration: that gave him objects with which to establish

his approach to colour boundaries in a more natural way, which then carried

over into his later abstract work. I was reminded of Tom Wesselman explaining

his desire to paint figuratively against the background of Abstract

Expressionism as being an acceptance that he needed ‘definite elements to

manipulate in a very specific and literal framework’. That fits with the other

main reason Stubbs liked the Ocean Park series: the geometric elements gave something

for the gestural brushwork to play against. That allowed Diebenkorn to set calm

against tension. In contrast, Carr found ‘his divisions, edges and pauses

slack: they fail to generate the tension found in Martin, Newman or Mondrian’s compositions’.

She liked Berkeley #57, 1955, for its ‘honesty and humility’, but

was less attracted to the ‘confidence’ which Stubbs had identified in the later

work. Niederberger was unenthusiastic about all phases, even though as a

student she said she'd been impressed by Diebenkorn and felt that was what

painting was about. Now she condemned the work as merely 'nice to look at'. She

admitted Diebenkorn operated well at the aesthetic level, but said he engaged

only the eye, not the brain. The essence of painting, she felt, should be ‘to

walk the tightrope of engaging both brain and eye so that there are both ideas

and aesthetics, but neither dominates the other’. If Diebenkorn does

engage the brain, it’s probably through the way he demonstrates the active

process of solving the formal problems which allow his work to appeal to the

eye: we can follow him thinking his way through a composition, and see how he

applies such Notes to myself as ‘attempt what is not certain’

or ‘be careful only in a perverse way’.

|

| Untitled (Ocean Park), 1971 |

That seemed to be at the core of Stubbs’

appreciation. He felt that the vehicle of the grid gave the later Diebenkorn ‘a

way to contain his expressive gestures and the interesting and radical

awkwardness of his colours successfully’. Blannin thought this 'sophisticated',

even though you can see the signs of struggle. Simpson agreed, suggesting that

Diebenkorn had found an approach which was quiet, not because he lacked energy

or desire, but because he was ‘unegotistical’. ‘The coolness is not

impersonal’, he opined, ‘even though it avoids big heavy self-aggrandising

gestures’. Stubbs agreed that Diebenkorn had desire, ‘even if it was

very cool’, though he conceded that he was ‘more impressed than moved’ by the

results. Maybe that absence of emotional impact relates to Diebenkorn’s

contented and straightforward personal life, which provided him with none

of dark materials of such predecessors as Gorky, Rothko and Pollock. I

liked a drawing from 1971, in which the strategic pentimenti and the dialogue

between ruled and freehand lines works well. Moreover, drawing directly onto

the canvas with paint is fundamental to the Ocean Park series, and John

Elderfield has suggested that Diebenkorn’s drawing remains ‘the mortar between

bricks, hardly noticeable at times of what holds a structure together and keeps

its firm’.

|

| Cigar Box Lid #4, 1976 |

A gap emerged, then, between enthusiasts of the

late work and those who thought it merely safe and tasteful, even if it

embraced an artful messiness – ‘abstract art’, it has been said, ‘for people

who don't like abstract art’. Thompsett felt that Mondrian - an obvious

influence behind the Ocean Park series - succeeded better because his approach

was much tighter. Yet it was precisely the tension between tight and loose

which appealed to the Ocean Park advocates. Moreover, as Blannin pointed out,

Mondrian himself developed his frameworks instinctively, and the paintings

themselves (as opposed to reproductions) are alive with far from neutral

brushwork.

|

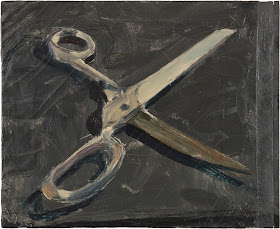

| Scissors, 1959 |

Do Diebenkorn’s paintings have ‘personality’? Perhaps

of places rather than of people, was the view, even when he is depicting

people, as they tend not to be individuated as characters. Indeed, one could

argue that a small depiction of scissors is more of a portrait than the

mid-period works featuring people, who seem present mainly for their abstract

qualities. All the same, it was agreed by all, the personality of the painter

comes through in a painting, even if it is through choice of colour and

structure, not through gesture. The late work, I felt, is monumental

yet intimate.

Overall, then, the mixed verdict showed at least

that there’s enough variety and interest in Diebenkorn’s work to generate

differing opinions. That itself suggests the work has virtues, even if they are

hard to pin down given the somewhat subjective nature of the judgements

involved – and all six artists said they’d enjoyed their visit, even if the

substance beyond that enjoyment could be called into question.

|

| Katrina Blannin, Diamond Light 50, 2014, (Tonal Rotation with Pink/Green: Blue/Black Demarcation) 2014, acrylic on linen, 50 x 50cm |

| ||||||

| Dolly Thompsett: The Secret Life of Mrs Andrews, 2014, Ink and mixed media on patterned upholstery fabric, 90x67cm |

|

| Christina Neiderberger: Chinese Whispers (after Brice Marden), 2013 - acrylic on canvas, 150x130cm |

|

Michael Stubbs, Digiflesh #8, 2013 - household paint, tinted floor varnish, spray paint on MDF, 153x122cms |

| ||

Claudia Carr: E's rocks and blue, 2013 oil on canvas on board, 35.5x22.5cm

|

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.