I reviewed two of the many exhibitions and events at the interesting Nour Festival of Arab culture as at www.rbkc.gov.uk/subsites/nour.aspx for the Festival Blog... The Festival (20 Oct - 8 Nov 2015) has finished, but both these shows run on to late November and are well worth visiting.

Marwan: Not Towards Home But The Horizon

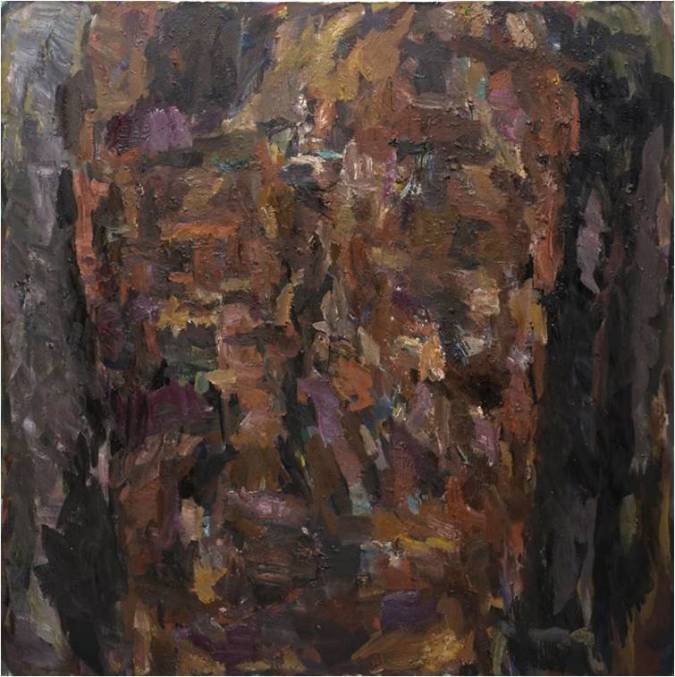

Marwan Kassab-Bachi, Untitled, 2014

The Mosaic Rooms, a well-appointed privately funded institution, makes an excellent showcase for the work of the Syrian painter Marwan Kassab-Bachi,

generally known just as Marwan. Based in Berlin since 1957, he settled

in Germany by chance but is now well integrated into German society.

In fact, fellow student Georg Baselitz

is a more obvious influence on his artistic development than any Arab

forebears. Marwan has children with his German wife, and became the

first Arab member of the prestigious Akademie der Künste

in 1994. That said, Marwan has kept in touch with his roots in

Damascus, and his paintings might be seen as applying western modernist

methods to Oriental concerns.

The exhibition is spread out over three rooms: the first contains

seven large oil paintings of semi-abstracted heads, the subject on which

Marwan has concentrated for the past forty years; the second is

dedicated to the series of etchings 99 Heads; while the third

gives fascinating background material through paintings from the 60s,

recent works on paper, and sketchbooks. The large untitled examples

shown are from 1977, 1987, 1992, 2001, 2019, 2010 and 2014. The

earliest has a more clearly delineated head, and established more volume

than the flattened planes of the later works – though, even they retain

a ghostly echo of the cubist language which sought decidedly opposite

ends. Longer-term, there is a move from the dark, dense, multi-layered

build-up of paint towards a more open, fluid, brighter and thinner

application, becoming gradually more lyrical as we move through to this

century’s work.

The faces aren’t hard to perceive, given the brain’s pareidolian

instincts, but they are abstracted enough to come in and out of focus,

so that image and surface take turns at the front of our perceptions.

This to and fro imparts a restless energy, which might suggest ‘inner

faces depicting mental conditions always in flux’, in Jőrn Merkert’s

words. This leads to the question: what conditions are being expressed

here? You might say that Marwan uses the face merely as a ground for

abstraction, were it not that the face is such a strong subject that it

almost automatically picks up an existential aspect. The titles of

Marwan’s shows have tended to play on this: ‘Topographies of the Soul’

preceded ‘Not Towards Home, But The Horizon’. Merkert is in no doubt:

‘Marwan is obsessed by faces because for him they are a means of

expressing the dramatic depth of life.’

|

| Installation shot |

Such readings are in tune with the fragmentary presentation of

figures, and the anonymity – and hence universal applicability – of the

faces. While the show’s catalogue states that: ‘though the nature of

his work calls attention to the surface, Marwan is in fact concerned in

revealing what lies beneath’, I’m not persuaded that this is in the

paintings themselves. One cannot read facial expressions or emotional

states into these landscapes of the mind – if that is what they are – so

any ascription of feeling must come from the viewer. I suspect the

existential aspect is a projection built from statements about the work,

and given additional weight by the fraught nature of German and Arab

history over Marwan’s lifetime (he is 81) and the current trauma of

Syria in particular.

The etching series 99 Heads, 1997-98, making its London

debut here, pushes the heads further towards the unrecognisable than do

any of the paintings. That’s largely a function of small scale and lack

of colour to guide the eye, assisted by the insertion of horizontally

aligned heads, and half-seen heads looking over tables, as well as the

usual frontal portrait formats. The series references Sufism and the 99 names of God, a place always being left to represent the 100th

name as a place of God’s light. Curiously, although there are 99

etchings arranged as a grid which covers a suitably sized room, some

contain more than one face. Consequently there are in total more like

105 heads, which left me scratching mine with regard to the match with

99 names.

Marwan Kassab-Bachi, Munif Al-Razzaz, 1965

The third room has early – graphically and directly expressive –

figures and marionettes, drawings, sketchbooks, large watercolours not

dissimilar in effect to the most fluid recent oils, and my favourite

part of the show: heads painted in rapid impasto directly onto the small

boxes in which the paints came. The sculptural projection, everyday

material and direct link to the studio process all feel appropriate. As

in the etchings, the severely reduced scale works naturally with the

lack of image resolution, leaving us with the spontaneous essence of

Marwan’s project.

The Guardians

Leighton House Museum to 29 November

The

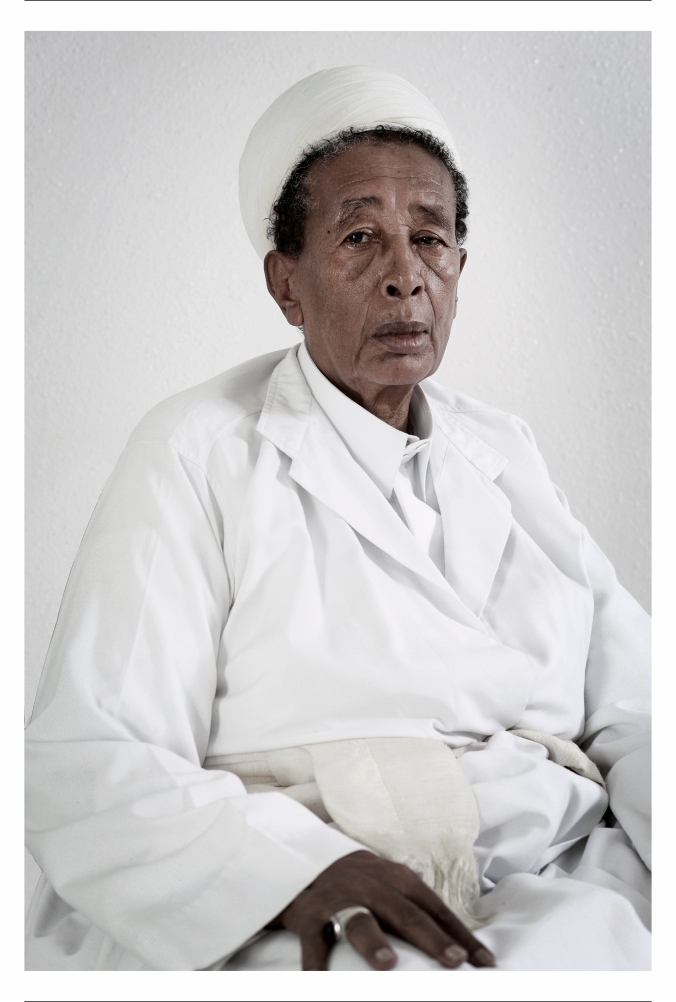

Guardians. Saeed Adam Omar (Late Sheikh of the Guardians) by Adel

Quraishi. Courtesy the artist & The Park Gallery, London

As his contribution to the Nour Festival, Saudi Arabian portrait photographer Adel Quraishi

has focused on what must be one of the most affecting groups available:

the handful of surviving Guardians of the Prophet’s burial chamber

at Medina. Prophet Mohammed lived, died and is buried there, and every

Muslim aims to visit the site at least once. Since the Ottoman Empire,

the keys to this holy site have been kept by eunuchs – originally from

Abyssinia, later wider in origin. They are eunuchs who entered the

role long ago, and are now at least 80 years old – one is said to be

110, which would fit with research suggesting that reduced testosterone

gives eunuchs increased life expectancy. Nonetheless, three of the eight

pictured in 2014 have died since the photographs – the only ones ever

permitted – were taken, and only three remain fit to carry out their

full duties. The Guardians are eunuchs, not because they have access to

women’s accommodation, but for the spiritual aspect of a faith that is

undistracted by sexual desire and uninfected by ritual impurity. They

are revered as mediators who cross boundaries, and there’s also a sense

in which time is suspended for them, as they have never gone through the

changes of adolescence. That state matches the suspension of time said

to occur in the well-preserved state of the Prophet’s body.

No new Guardians are being taken on, so where once there were

hundreds responsible for all aspects of running the mosque complex, the

remaining few spend their days in a small room connected to the burial

chamber itself. They pray, clean the floor with rosewater and look after

the set of keys which must be used in a closely-guarded sequence to

access the chamber. Even Quraishi was not allowed to photograph the

keys, but he was able to take an image of the chamber through which a

constant stream of pilgrims pass: we see the architectural and

decorative detail, but a long exposure time converts the worshippers to

abstract marks passing through. Quraishi’s project, then, makes the most

of the photograph as record: to look at the eight faces ranged – life

sized or somewhat larger – around the ideally suited dimensions of

Leighton House’s contemporary exhibition gallery is to look at the only

pictures ever taken of an 800 year tradition which is set to disappear.

So how do the eight portraits operate as images? The late Sheikh (or

Chief) among them, Saad Adam Omar, and his successor, Nouri Mohammed

Ahmed Ali, look to have a more assertive presence than the other six,

among whom there is less sense of personality. These are pious and

self-effacing men, who have spent at least the past 60 years in

ritualised routine. Quraishi describes them as humble and balanced men

who put him at ease. They come across as dignified, but subordinate to

their roles. Quraishi could have emphasised this by employing a serial,

standardised set-up in the manner of the Bechers. However, though the

octet are all shown against a plain white background (as photographed in

their small and little-used office) and though all prints are an

imposing 191 x 135cm (commensurate with important subjects), there is

considerable variation. The scale at which the Guardians are shown, the

degrees of crop, and their poses all vary. So do their clothes: they

wear state dress, but have no uniform as such, nor is there any

indication of rank: they are given a new robe each year, and choose

which one to wear and with what. All wear a green belt, visible in

several photographs and characteristic of Medina (whereas their

equivalents in Mecca wear red belts). Otherwise, the colours are

restrained: browns, golds, whites.

The portraits, then, are more varied than might be expected, but only

to set you wondering: is that an indicator of the men’s underlying

variation, or the extent of it? The effect might be contrasted with Thomas Ruff’s passport-style photographs, which pretend to impose uniformity on a patently disparate group; or with August Sander’s People of the 20th Century, which revolves around the range of jobs performed. Overall, The Guardians is a compelling representation of the totality of a rare group, and Leighton House Museum,

with its Arab Hall lined with an extensive collection of Islamic tiles,

is an appropriate and atmospheric location for it. That the portraits

were taken at all made that impact likely; and though Quraishi could

undoubtedly have carried the project out differently, the way he has

done enhances the effect.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.