THE HYPER-PAREDOLIAN DING YI

Ding Yi at Timothy Taylor, London

19 May – 24 June 2017

Ding Yi, now in his 50’s, is one

of the most established Chinese painters, but does not conform to the

expressionist or pop-inspired approaches

which often seems to dominate the category, at least at auction. Rather, he has

been painting abstracts using the cross – both ‘x’ and ‘+’ – as his sole

content since 1988. The crosses’ origins lie in the most basic marks in offset

printing (Ding’s student job was in the printing industry). That morphed into

an interest in textiles – much of Ding’s late 90’s work was painted onto

Paisley tartan, nodding to its import history in China. Over those three decades Ding has altered almost

everything – ground, medium, colour, scale, regularity, infection – but all his

works have been called Appearance of

Crosses. That title suggests a façade, a field of sense data, and site of

mutable interpretation: they may appear like crosses, but what are they really?

Ding likes to set himself constraints,

and the show at Timothy Taylor consists of seven new paintings which are

consistent enough to make clear the particular set he was working within in

2016. All seven are 240 cm square, and described not as ‘acrylic on wood’ but as

‘mixed media’, signalling that the basswood is an active material – not just a

passive ground. All use black, white,

grey and a chromatically close pair from what Ding says are ‘the six available

fluorescent colours’: four of the new paintings use green and yellow, three use

red and orange (the other fluorescent colours

– blue and pink – don’t feature here).

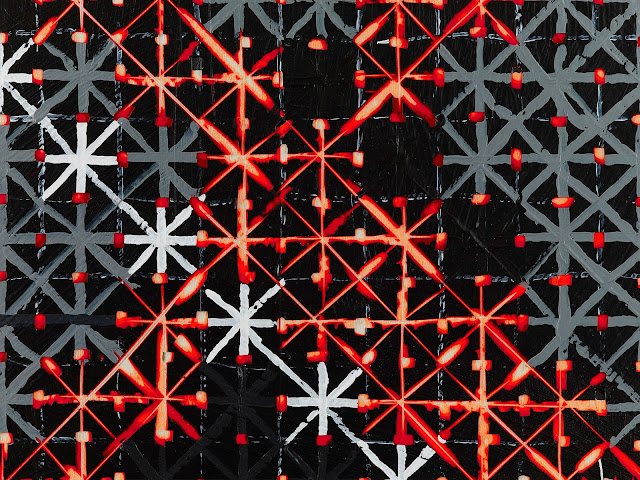

The paint is applied in pre-determined layers: in order of application

we see a background of hot fluorescence which erupts through extensive black, which

is applied second but then partly cut away, so evoking a woodcut. The top layer

is of crosses in greys and whites of varying intensity, which destabilises the super-position

of raked and diagonal grids.

|

Appearance of Crosses 2016 – 10 |

It is possible to read many subjects from the world into Ding’s abstractions: the graphic constituents of printing processes and the warp and weft of magnified cloth, yes, but also magnifications of atomic diagrams or cellular activity, computer screens full of coded information, illuminated advertising hoardings, scaffolding, a cityscape, the night sky… Moreover, the shapes made by the more prominent crosses operate at the macro level to suggest diamonds, TV static, or – in a neatly totipotent move – a cross or star (Appearance of Crosses 2016 – 7). It may be that little of this is deliberate, though Ding says that, despite being an abstract artist, in recent years he ‘has started to take note of the urban development of Shanghai’. That has seen its population grow by 10 million to 26 million just this century. That make it natural to assume an urban influence on his current work, especially as its fluorescent colours suggest the excitement and artificiality of city life.

|

Appearance of Crosses 2016 – 7 |

Ding’s work has its most obvious

western resonance in Mondrian’s also-square Broadway

Boogie Woogie, 1942-3. Ding acknowledges the influence, alongside Chinese

traditions. Yet it is interesting to consider other possible parallels. Ding

paints one work at a time in strict sequence and without assistants, which is a

test of stamina and persistence given the many thousands of crosses, the

accumulations of actions and time, inscribed on each, Not for nothing has his

approach been described as ‘excessive minimalism’: large works can take up to

two months to complete. Yet endurance isn’t a focus as it is in Roman Opulka’s number

paintings. Nor is Ding meditatively repeating a set intent, as does Peter

Dreher in his thousands of paintings of a water glass. And though the crosses

might be seen as meaningless writing, Ding’s marks remain more separately nuanced

than in work – such as Irma Blank’s or even some of Cy Twombly’s - which

accumulates writing into abstraction.

Ding’s method is closer, perhaps, to the sensitive exploration of grids and stripes in Agnes Martin or better, given the prominent brushwork and backlit glow his work shares with these Appearance of Crosses – of Sean Scully. The latter, also shown by Timothy Taylor, is indeed a friend of Ding’s. I was also reminded of Peter Halley, who has explored relations between cell-like structures for thirty years, often uses fluorescent paint, and is explicit about his apparently abstract paintings representing ‘a conversation between being connected and not being connected’.

|

| Appearance of Crosses 2016 (detail) |

Ding’s method is closer, perhaps, to the sensitive exploration of grids and stripes in Agnes Martin or better, given the prominent brushwork and backlit glow his work shares with these Appearance of Crosses – of Sean Scully. The latter, also shown by Timothy Taylor, is indeed a friend of Ding’s. I was also reminded of Peter Halley, who has explored relations between cell-like structures for thirty years, often uses fluorescent paint, and is explicit about his apparently abstract paintings representing ‘a conversation between being connected and not being connected’.

|

| Appearance of Crosses 2016 (detail) |

Ding’s crosses, then, may have

become simply the language he uses, but their accumulated units prove ambiguous

enough to allow both microscopic and macroscopic projections from the world,

and at the same time to trigger multiple echoes of other abstract painters. Given

that breadth of potential for suggestion, Ding’s work might be termed ‘hyper-pareidolian’.

|

| Appearance of Crosses 2016 – 8 |

The theoretical setting, full of

ambiguity between expression and meditation, is good. What about the paintings

themselves? They look, from a distance, as if they could be computer-generated,

but proximity shows how Ding dynamises his surfaces (he did have a ‘mechanical’

period in 1988-91, but told me he now likes to demonstrate his human engagement).

|

| Appearance of Crosses 1989 -7 |

Appearance

of Crosses, 2016 4-10 aren’t regularly patterned. Rather, Ding responds to his

initial marks in an ongoing call and response, typically working from both

sides of the panel inwards. He reveals his hand by varying both the thickness

of the underlying layers of paint, and the weight of his touch as crosses are

applied (so that the underlying gradients are differentially picked up). The

retinal effect draws the viewer in to the exploration of absorptively-scaled

fields. And that led me back to Shanghai: it’s easy to think abstractly of the sheer

numbers of people and buildings involved a doubling of the population, but if

each individual mark stands for a person, Ding’s coruscating visions of the

city, for all their plenitude, speak of individuals, too. That might, despite Ding’s distance from

‘political pop’ or ‘cynical realism’ be taken to reflect the tensions very

obviously present, in the sharp transitions of Chinese society, between control

and freedom.