The ING Discerning Eye Exhibition is an annual show of small-scale works chosen by a panel of six prominent art world figures – two artists, two collectors and two critics. This year’s edition presents some 400 works at the Mall Galleries from 11-21 November. I was given an early sight of what will be in the show in order to select ten works to talk about. My choices don’t pretend to be representative: I just went with what interests me, which tends to be slightly unusual work combining aesthetic and conceptual appeal. Five of my choices happened to have some sort of feminist perspective, and the first two filter that through the lens of art history. If that makes them sound similar, not so…

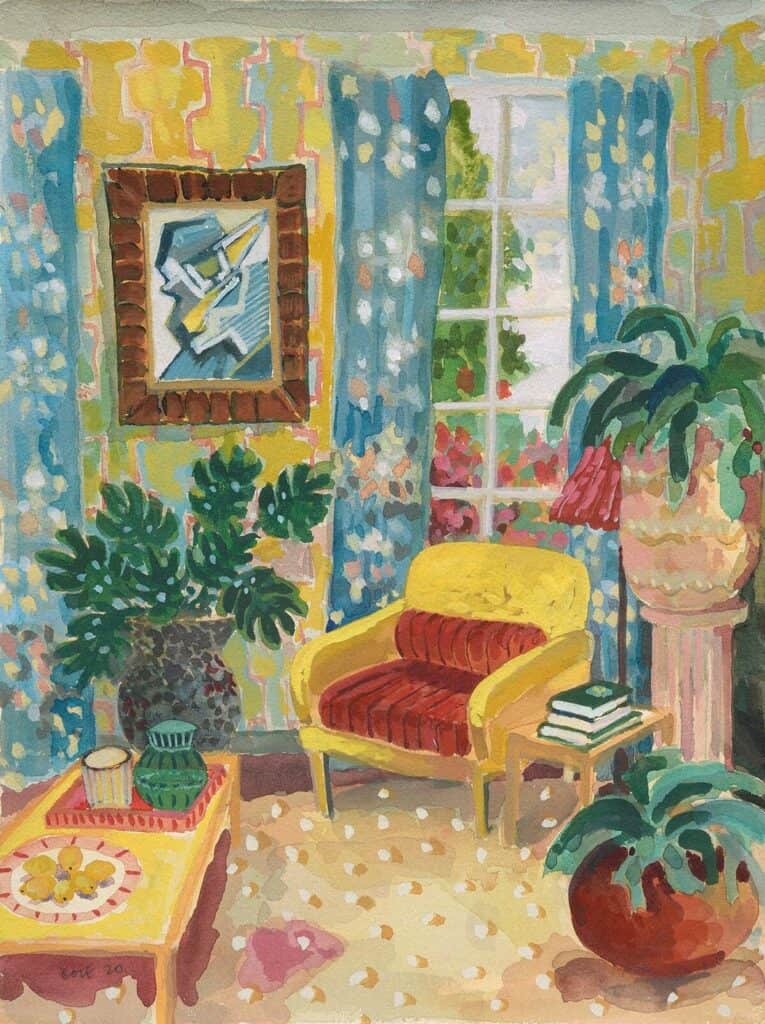

Lottie Cole: Interior with Helen Saunders, 2020 – watercolour and gouache, 50 x 40 cm (top)

A beautifully painted interior infers, slightly mournfully, the absence of an owner with a refined sense of chromatic coordination. But Lottie Cole is also framing the history of art. Go back to the time when the prominent ‘painting within the painting’ was made, and the woman’s place was commonly considered to be in the home. Yet the housewife in this case may be an exception, in the studio, making art unlikely to be taken seriously by the male-dominated establishment. That’s what Helen Saunders (1885-1963) was a doing in 1915 – the dynamic diagonals on the wall are those of the under-appreciated Vorticist’s ‘Abstract Composition in Blue and Yellow’ from that year (below). Actually, it’s in the Tate’s collection, though typically – as now – it’s not on display, even though the stock of Saunders and her sister Vorticist, Jessica Dismorr, has risen recently. As for Cole, you can typically find her work at Long & Ryle – just a couple of hundred yards from Tate Britain, but not quite in it.

Anne von Freyburg: Untitled (After Fragonard), 2021 – Mixed media painting: Acrylic ink, crystal-beads, various textiles, polyester wadding and hand-embroidery on canvas, 50x40x3 cm

Dutch artist Anne von Freyburg starts by distorting a historic painting on Photoshop – here Fragonard’s ‘Girl with a Dog’, c1770 (below), which has some of the famous cheek of ‘The Swing’ as the girl lies half-naked on a bed. She then paints that onto her ground, cutting out and arranging a wide variety of textiles to – mostly – cover the paint, and sewing those into place with wadding inserts to push even further into the rococo excesses of her sources. Why so? To challenge the historic dismissal of textile and decoration as more feminine and less intellectual than the serious art of oil painting by – effectively – ‘painting in materials’. Yet von Freyburg evidently enjoys fashion fabrics for their own seductive sake, even as she takes them to a place she describes as ‘wobbly, uncanny and grotesque’, contradicting the beauty-driven commercial intent behind their production. Last week von Freyburg won the The Walter Roberts UK New Artist of the Year 2021.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard: Girl with a Dog, c1770

Jean-Honoré Fragonard: Girl with a Dog, c1770

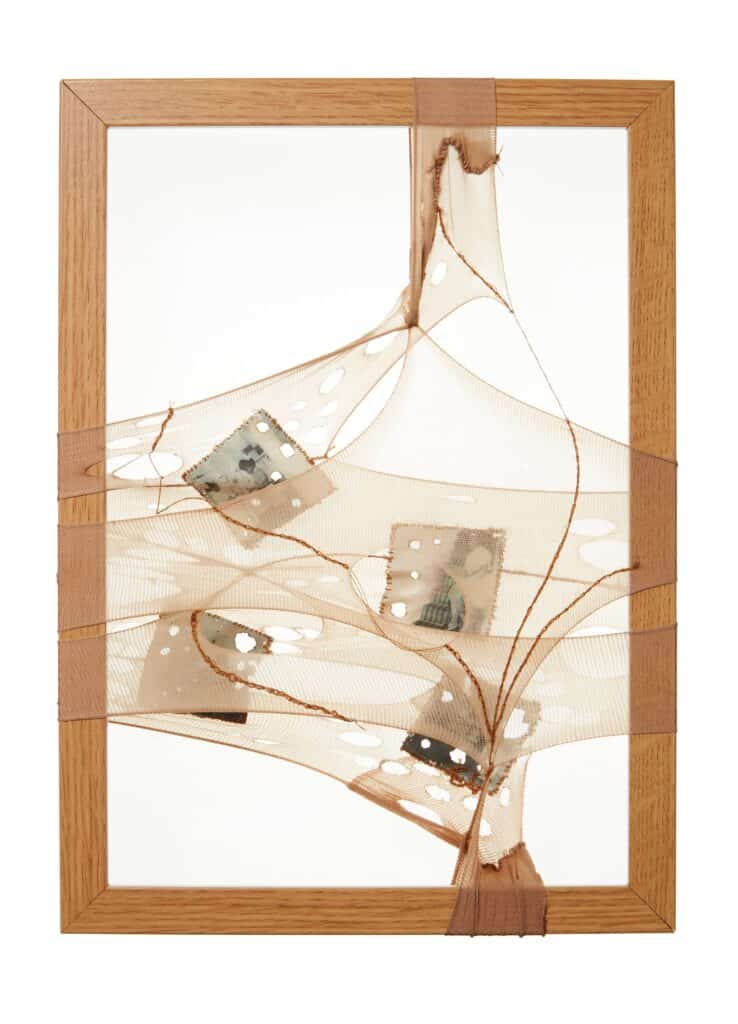

Enam Gbewonyo, Untitled II, 2019 – Burnout used nylon tights, vintage family photographs on tea stained recycled paper, cotton thread hand embroidery on photo frame, 24 x 33 cm

Enam Gbewonyo, Untitled II, 2019 – Burnout used nylon tights, vintage family photographs on tea stained recycled paper, cotton thread hand embroidery on photo frame, 24 x 33 cm

Enam Gbewonyo is by no means the first to use tights as her medium – she’s been in a group show of 21 artists with exactly that constraint (‘Gossamer’, Carl Freeman gallery, 2019). Gbewonyo, who combines Ghanaian descent with a background in the New York fashion world, addresses the politics of hosiery. She sets up background images in a critique of voyeurism, and references the many years in which the only ‘nude’ colour available was for white flesh, so women of colour tended to wear black tights – a symbol of their marginalisation. Gbewonyo embroiders lines on the nylon to represent the veins which are the same under all skins. Those lines, together with the holes in the tights, return us to the language of abstract painting. Compare, for example, Alberto Burri’s use of burnt plastic, in which the choice of matter was equally critical to the resulting aesthetic.

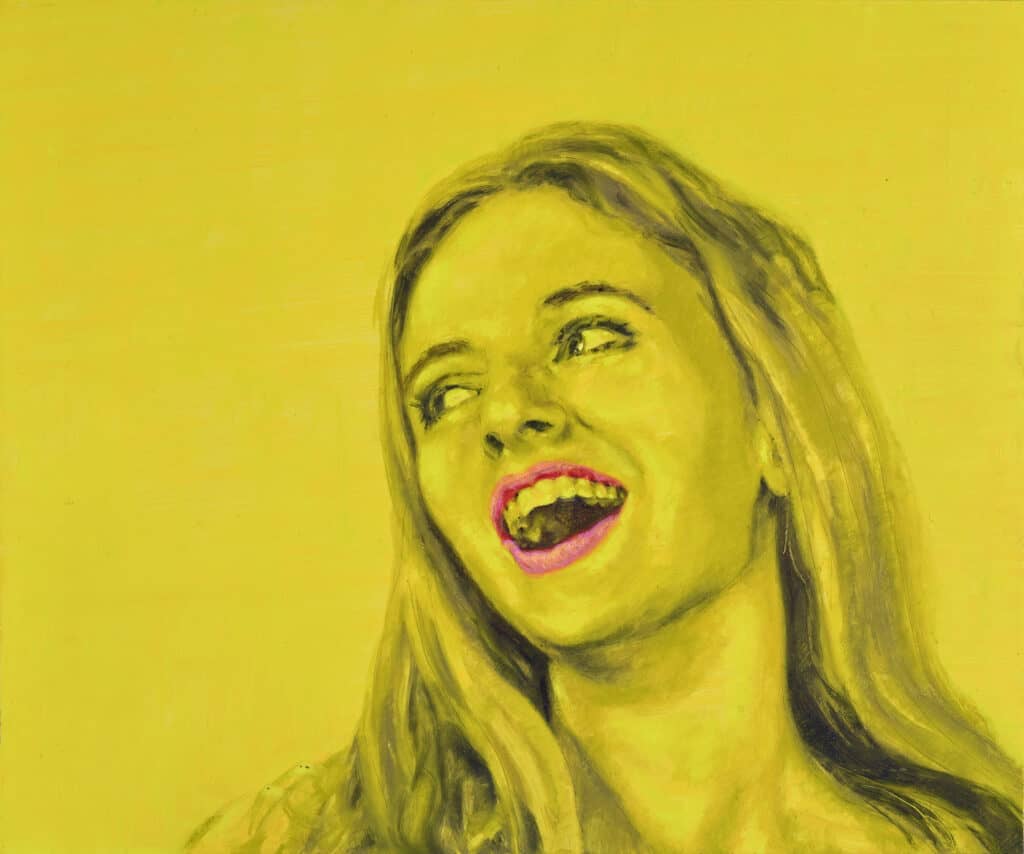

Roxana Halls: Laughing Head IV and (at top) Laughing Head V, 2021 – oil on aluminium, 25 x 30 cm

Roxana Halls smuggle a radical lesbian feminist agenda into the apparently conservative means of realist oil painting. Observing how often women subconsciously exercise self-surveillance, so deeply is female self-control embedded into cultural expectations, she likes to depict women enjoying behaving ‘badly’. That includes them laughing in situations where you wouldn’t expect it: eating salad, while smashing things up, after a plane crash… She cites Helene Cixous telling the story of the Chinese general Sun Tse, who decapitated a group of women he was trying to train as soldiers, so disconcerted was he by the persistent laughter with which they respond to his orders. Here the laughter is presented plain, but Halls is still co-opting the portrait – another establishment tradition – as a form of political resistance.

Miriam Austin: Gimmel: Laminariales (Tools), 2018 – aluminium, steel, thread, 44 x 9 cm

These elegantly simple forms take on multiple resonances in the context of Miriam Austin’s performative and sculptural practice, which often operates by imagining alternative societies. Consider the threefold title. The double loops suggest those of a medieval ‘gimmel ring’, comprising interlocking bands which were separated and worn by each partner prior to marriage, then joined and worn by the woman afterwards. So, intimacy is implied. As ‘tools’, says Austin, they are ‘suggestive of the forms of the human body and biomedical technologies, as well as implements used in the whaling and sealing industries – and hover ambiguously between a symbolic presence and a more threatening one’. That symbolism may be linguistic: perhaps linked to a community from an aquatic future suggested by the reference to ‘laminariales’, the kelp group of seaweeds; or to Austin’s particular interest in Laadan, the feminist language designed to liberate expression from the patriarchal forms of historic languages. The ‘tools’, she says, could operate similarly as ‘primarily symbolic forms that speak of embodied experience’.

Benjamin Deakin: Riser, 2021 – oil on panel, 30 x 45 cm

Benjamin Deakin has travelled the world widely – including cycling through the Andes and undertaking residencies in Lisbon, Iceland, Canada and Nepal – and channels that experience into depicting imaginary places. A retro sci-fi feeling emerges from combinations of the real. ‘Riser’ is from a series that uses an architectural template of common shapes, but oriented differently to match the various functions and characteristics implied by the titles: this structure spreads out upwards, whereas similar components in ‘Congregator’ look set to facilitate meetings, while ‘Slider’ adds a downward-sloping chute for swift egress. That may serve to emphasise the empiricist point, already evident in Deakin’s work, that all imagination can necessarily be traced back to contact with the real. Formally, the approach enables Deakin to make the most of the license it gives him to allow abstract considerations to lead decisions about colour and form.

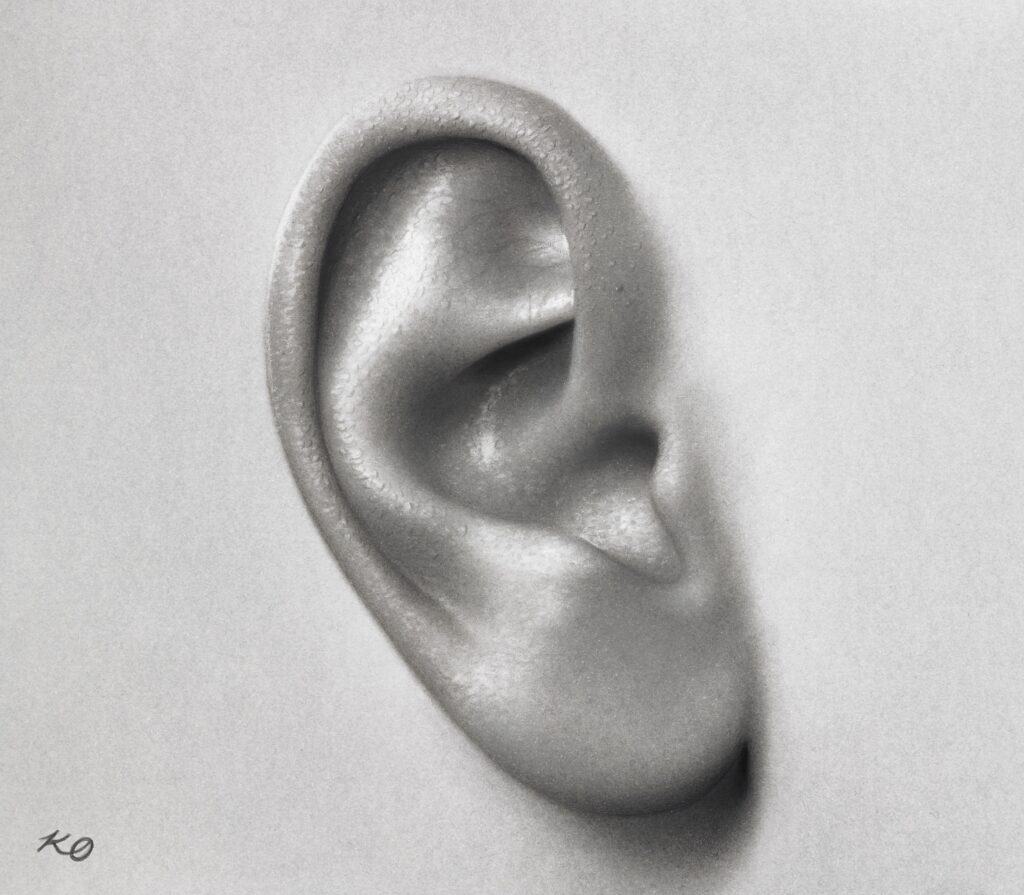

Kelvin Okafor: Untitled, 2020 – charcoal and graphite on paper, 8 x 9 cm

One of the smallest works in the show depicts – life size, I suppose – an ear. It’s beautifully and hyper-realistically realised, but in splendid isolation: there are no signs, such as nearby hair, of the head to which it should be attached. That could place it in the tradition of the life class sketch, but it looks too finished for that, leading me in two other directions. On the one hand the purity of focus draws attention to the abstract sculptural merits of the form: I thought of the sculptures of Hans Arp. On the other hand, it could signal a traumatic detachment: I thought of the opening scene of David Lynch’s ‘Blue Velvet’, which zooms in on just such an ear in the grass. Moreover – to declare a bias – I like the slight paradox of concentrating visually on the site of hearing, and have even curated a show on the theme (‘Ears for the Eyes’, Transition Gallery, 2017).

Selma Parlour, Smack Dab XV, 2020, oil on linen, 41×31 cm

Selma Parlour layers her colours semi-translucently over a white ground, which provides a hint of backlighting and accounts for a fair chunk of the distinctive allure of this, one of the few abstract works to be shortlisted. Although you don’t have to look at it that way. Like many of Parlour’s works, this can be read as a painting of a room: an eccentrically-shaped abstract painting hangs – Smack Dab! – on a wall, with a second form which might be a sculpture if the lower section is a floor rather than a transition in wall colour. That ambiguates the space nicely, and teases us with the question: which is the referent and which the art? The game of decoding can also be tied into art history: Parlour’s 180 page PhD thesis referencing her work is called ‘Depicting Limits: Syntax, Abstraction and Space in Contemporary Painting’.

Callum Eaton: Cucumber, 2021 – Oil on Canvas, 30 x 30 cm

Callum Eaton lavishes considerable time and technical expertise on photo-realistic depictions of mundane items from everyday life. That’s an established way of elevating the commonplace for revaluation, but Eaton’s choices are surely a tongue in cheek deconstruction of that tradition. In the show, a cluster of plugs and a calculator showing a number that appears to spell ‘BOOBIES’ complement this cucumber. All three could be seen as smuttily sexual, the cucumber ramping up the phallic symbolism by the condom-like retention of its shrink-wrapping. That also makes for a comical – yet realistic – updating of the still life tradition. Moreover, the tricky matter of transparency is expertly handled. Could it even, to be more serious, be taken as a critique of the prevalence of plastic wrapping, a problem that supermarkets have only recently started to address?

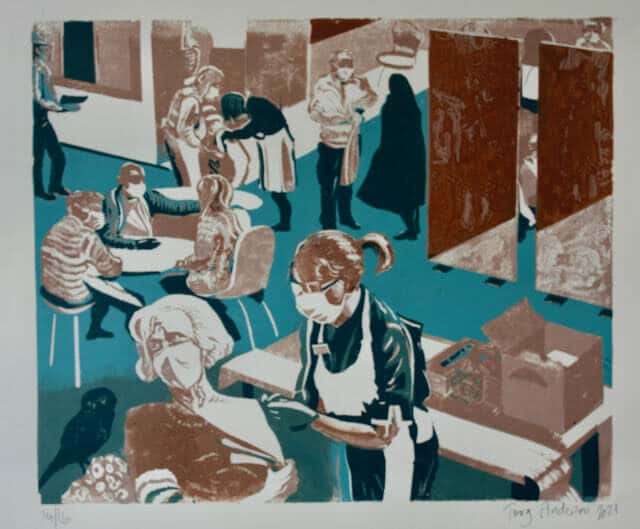

Tony Anderson, Vaccination Centre, 2021 – linocut, 37 x 40 cm

This is obviously topical, but Tony Anderson’s medium and aesthetic take us back to the interwar years, when Claude Flight and his famous students Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews developed the colour linocut as a means to explore the energy of the then-modern age. That led to World War II, and I think Anderson is making a comparison with the war time spirit and our response to the pandemic, as well as pointing to the limitations of progress. How far should be push the comparison? It’s sobering to think that, though 5m have died from Covid-19, there were 75m victims in the war. That aside, Anderson varies the degree of detail tellingly across the image, and unexpectedly includes an owl, perhaps alluding to the increased visibility of wildlife during lockdown as well as the symbolic strigiform connection with not just wisdom but also transition and time.

If I’d had another ten, incidentally, they might have been by Simone Brewster, Nicole Farhi, Marguerite Horner, Florence Hutchings, Debbie Lee, Hywel Livingstone, James Lloyd, Enzo Marra, Lee Maelzer, Simon Neville and John Walmsley.