LOVE LIFE: ACT 3

Jonathan Baldock and Emma Hart

Wind back a year, and Art Monthly carried my review of Love Life: Act 1, for which long-time collaborators Emma Hart and Jonathan Baldock turned London’s PEER gallery into a satirical version of a domestic space in which to reimagine the traditional seaside entertainment of Punch and Judy. This was not a fixed installation, as Act 2 was to follow – with extra work added – in the much bigger venue of the Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool, before the concluding Act 3 washed up, as it now has, in a single large and very tall space in the De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill. So what’s the same and what has changed?

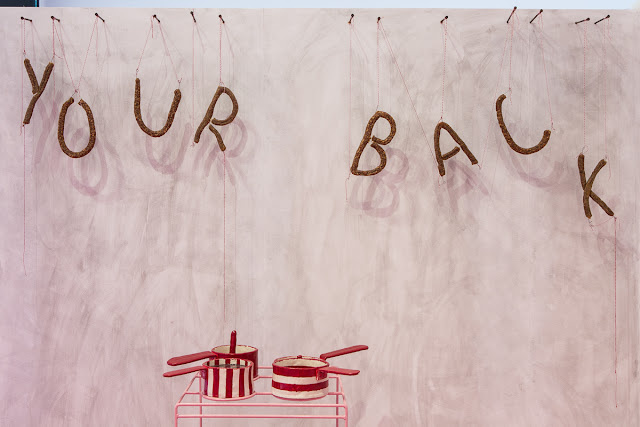

The atmosphere proves a constant: a domestic environment is crowded with gags which are funny but also dark, as underscored by the backdrop of innate violence, and the presence of multiple eyes which suggest surveillance. Visitors find themselves in the middle of a disputatious mise-en-scène, populated by objects which are nicely made but remain approximate, more like props than real things, though Hart does spell out one wall text in genuine sausages, slowly dripping fat, to keep us on our toes. The phrase ‘Your Back’ – and the work’s title I’ve Got Your Back suggest in equal parts protective cover in a military action, that we are backstage, and that one character has annoyed the other.

The show’s sound is

still the 45 rpm record Jon and Emma

in which Baldock and Hart call out each other's names. Their tones vary from

pleading to pained to provocative, in a routine which derives, appropriately,

from a 1950’s puppeteer. Both artists have practices which tend naturally

towards the humour and grotesquery of Punch and Judy, both focus on the body

and the handmade, both use various materials but especially ceramic, both like

excess and dislike control. That makes it tricky to tell who made what – and I

don’t think they much care about that. The broad distinction is that Baldock

creates the scene and Hart populates it with sculptures which – somewhat

paradoxically – portray events.

Here We Go Again summons chase and flight through ceramic feet wearing glove puppet socks, the ends of which form potentially nagging mouths; Bang cuts the shape of a comic explosion from a door which was evidently slammed; and three ceramic speech bubbles jut into the space so that they can be read from both sides. That, and their resemblance to beak-nosed profiles, explains their title You two-faced lying motherfucker.

Here We Go Again summons chase and flight through ceramic feet wearing glove puppet socks, the ends of which form potentially nagging mouths; Bang cuts the shape of a comic explosion from a door which was evidently slammed; and three ceramic speech bubbles jut into the space so that they can be read from both sides. That, and their resemblance to beak-nosed profiles, explains their title You two-faced lying motherfucker.

The principal differences between Acts 1 and 3 are location, layout, new works made during the Blackpool run, and the passage of a year. The De La Warr overlooks the sea, the backdrop of which connects more naturally to the tradition of Punch and Judy shows than an East London streetscape. The single space allows Hart and Baldock to subdivide it with screens which suggest both that we are backstage of Punch and Judy (as indicated by a wall painted to mimic the traditional red and white striped awning of a puppeteer’s tent) and in the house – or stage set of the house - of the couple, as played by the artists in a film which is one of two main new works. Love Life, 2017, sees them don comedy noses to engage in bickering and slapstick (a word which derives from Punch’s weapon of choice). Baldock makes a wimp’s job of attempting to turn over frying sausages with his fingers. Hart bashes dough into shape with a force which looks cathartic. We watch on a flat screen TV from a comfortable sofa, but overlooked by Baldock’s The Giant Hand, a monstrously sized child in a baby-walker with its single eye a film of Baldock’s own on a small screen. Probably not what your love life needs.

That figure isn’t

new, but the biggest piece at Bexhill is. In a further distortion of scale – which

adds to the confusion of adult with child perspectives, of everyday with

fantastical worlds – a ten foot high thumb. Under

the Thumb, 2017, made by Blackpool’s Illuminations Department, is mounted

high and seems to press down on the whole installation, so much so that the

carpet spreads out in an ooze of pink. When we see film-Hart hitting film-Baldock

with a stick, we might think of what is sometimes said to be the original ‘rule

of thumb’ – that a man could beat his wife provided only that the stick was no

wider than a thumb. And if it’s more likely that the phrase actually came from

carpenters using their thumbs as a handy measuring tool, the first joint an

adult thumb measuring roughly one inch, then that fits in with the

approximating tendencies of the stage

set.

The extra space suits the installations of domestic machinery, which can be given separate partitioned ‘rooms’. They appear to have the household’s conflicts built in: in Baldock’s Out Damn’d Spot!, a tide of blood-red clothes tumble out of a washing machine. On the hob, ceramic eyes and other organs are cooked alongside turd/livers in saucepans with tongues for handles (Baldock’s It’s Not Burnt, It’s Caramelised). The record player, absurdly sexualised by the addition of breasts, has its own rather cell-like space.

The extra space suits the installations of domestic machinery, which can be given separate partitioned ‘rooms’. They appear to have the household’s conflicts built in: in Baldock’s Out Damn’d Spot!, a tide of blood-red clothes tumble out of a washing machine. On the hob, ceramic eyes and other organs are cooked alongside turd/livers in saucepans with tongues for handles (Baldock’s It’s Not Burnt, It’s Caramelised). The record player, absurdly sexualised by the addition of breasts, has its own rather cell-like space.

Times have changed, too. Love Life I opened on the day of Trump’s election, which made it a little harder to love life. The impact of that has hardly diminished, but post-Weinstein the domestic violence to which the installation calls attention is now likely to trigger thoughts of the raised public profile of sexual harassment.

To quote myself, Love Life: Act 1 was sufficient fun that it was ‘hard to take the fighting implied too seriously. Perhaps that’s consistent with Punch and Judy’s arguments being predicated on underlying harmony. But is that the way to do it? How would it be if the artists fell out bigtime and their enmity was enacted in the gallery?’. Unsurprisingly, that hasn’t happened. Act 3 is Act 1 rearranged and expanded, its tenor and impact enhanced but not fundamentally altered. And it remains enjoyable enough for me to regret not seeing it in Blackpool as well. It might have been most at home there, alongside a real Punch and Judy professor’s tent from the local history museum, and in a brasher seaside resort than retirement-oriented Bexhill.

While touring shows do change due to availability

of particular works and the interaction of art and venue, the strategy of

developing an exhibition during its run is more often seen within a venue (as

in Wade Guyton’s ongoing four month engagement at the Serpentine). Love

Life dips a toe – or perhaps a giant thumb – into what could be an

interesting strategy of accruing new works and wider geographical frames of

reference around a consistent core as a show moves around the country.

Act 1: PEER, London, 9 November 2016 – 28 January 2017

Act 2: Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, 17 June – 12 August 2017

Act 3: De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-On-Sea, 21 October – December 2017

(all works 2016 unless stated)

All images are installation shots from Act 3.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.