My 'Interview of the Month', starting June 2021 and linked to a current show by each artist, is published online at Artlyst. My aim, rather simply, is to discuss some of the work in in more depth than is achieved in the typical press release. Here they are, most recent first, uploaded the month after they appear.

March 2024: Shuvinai Ashoona

Feb 2024: Emma Cousin

Jan 2024: Roland Hicks

Dec 2023: Paulina Olowska

Nov 2023: Ghislaine Leung

Oct 2023: Shirin Neshat

Sept 2023: William Cobbing

Aug 2023: Nick Hornby

July 2023: Mark Godfrey on Alighiero Boetti

June 2023: Callum Innes

May 2023: Sabine Moritz

April 2023: Carey Young

March 2023: Haroon Mirza

Feb 2023: Jonathan Baldock

Jan 2023: Jonny Briggs

Dec 2022: Richard Schur

Nov 2022: Romuald Hazoumè

Oct 2022: No interview (would have been Bernar Venet but I was hospitalised)

Sept 2022: Wolfgang Laib

Aug 2022: Charmaine Watkiss

July 2022: Mali Morris

June 2022: Peter Buggenhout

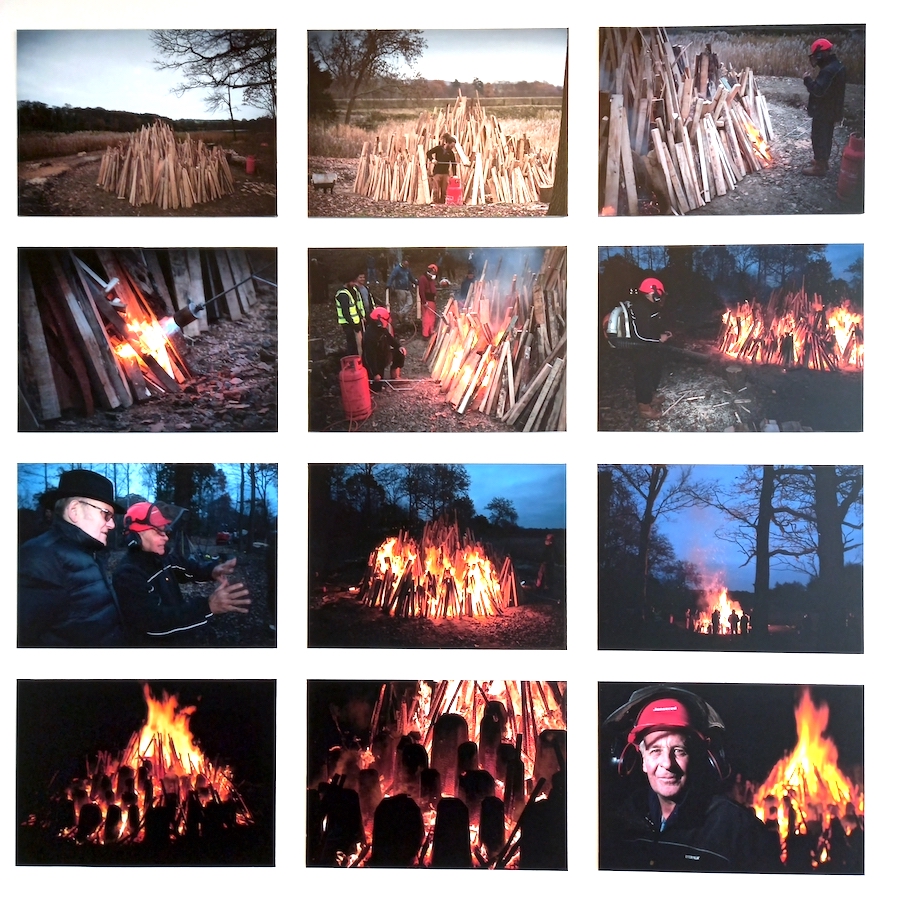

May 2022: Martin Parr

April 2022: David Nash

March 2022: Rana Begum

Feb 2022: Allison Katz

Jan 2022: Jyll Bradley

Dec 2021: Magnus Plessen

Nov 2021: Tania Kovats

Oct 2021: Ibrahim Mahama

Sept 2021: Alexandre da Cuhna

Aug 2021: Rosie Gibbens

July 2021: Spencer Finch

June 2021: Ena Swansea

Emma Cousin: Interview of the Month February 2024 – Paul Carey-Kent

Emma Cousin’s show ‘Tunnel Vision’ is the first in Niru Ratnam’s new space in Fitzrovia. The vibrant paintings were made either side of her giving birth in late 2022, and that experience is central to the figures who populate them. Not only do they perceive the world with the intensity of focus – or tunnel vision – that motherhood and art-making can both engender, they are revealed as incorporating interior tunnels in line with the enhanced awareness that Cousin found pregnancy bringing to her own interior structure. As ever, her work is fizzing with ideas…

What is ‘tunnel vision’?

Tunnel vision is the loss of peripheral perception with retention of central sight, resulting in a constricted, circular, tunnel-like field of vision. Goggles, glasses, and binoculars as well as medical illnesses are physical causes. For me, morning sickness felt like tunnel vision, everything apart from what I was directly looking at felt sickly. Painting through this lens was focusing and challenging. Psychologically, tunnel vision is when individuals focus on cues that are consistent with their opinion and filter out cues that are inconsistent with their viewpoint. In a political context, that can be negative. But this obsessive focus, where everything else falls away, is a mindset of funnelling that is useful in the studio.

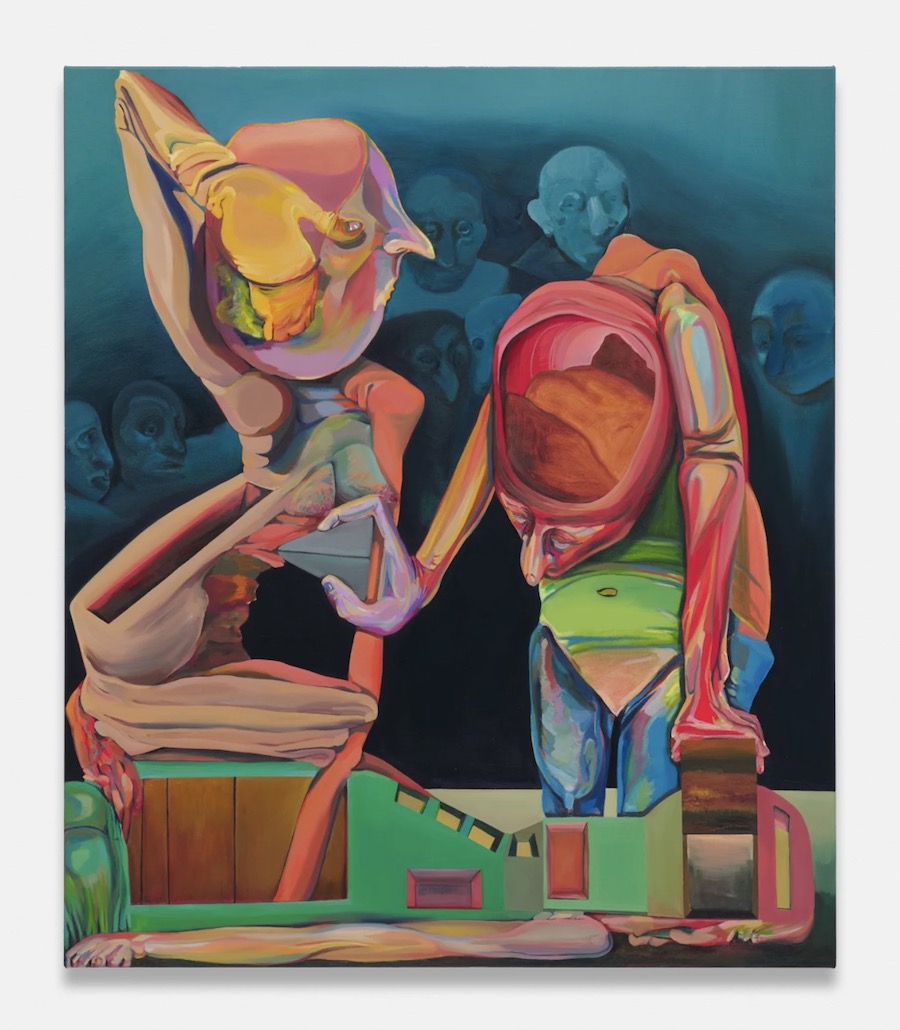

‘Tsog’, 2023 – Oil on canvas, 140 x 120 cm

All the figures seem to combine a ‘tunnel vision’ way of perceiving the world with an awareness of their inner structure of tunnels, but does ‘Tsog’ concentrate mainly on the internal aspect?

Perhaps… That’s about bringing the body back together, tunnelling inside, working out where how the tunnel would end – something comes out and you have to close the tunnel somehow. That’s the first time I’ve put figures in the background. They’re from Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson’, but they’re not watching the body being dissected, they’re watching how it’s put back together. It relates to my own body after birth: how to reassemble myself, how to deal with the void of the tunnel that had been filled. I imagined tunnelling to meet the baby, though of course you can’t – the baby tunnels towards you. But psychologically you do think like that, so it’s the union of inside and outside experiences. I was also thinking about tunnelling into yourself, to do with post-natal anxiety, when all the thoughts pile up like soil. Or how something was cut away, but to make something more beautiful. Beautiful and maybe gross at the same time. It’s like I’ve been inside-out for a bit! What would the flesh inside look like, and what would the flesh outside look like? It’s kind of amazing to have someone’s body inside you, and makes you aware of how much space there is inside you, and how you’re rejigged after having a baby. The way I’ve come back together is better than before in some ways – more efficient digestion!

What’s a tsog?

That’s a tool you use to cut peat. It looks like an extension of the body, fitting well within the hand. It works like a trowel, but also slices – that’s quite a brutal act but it creates these perfect bricks of geometry – an architecture of the land. That comes from remembering a holiday in the Outer Hebrides where I had watched peat cutters delve into the turf and hefting, turning, and laying out wedges of the inner soil in neat rows along the cleft they had cut into. They tunnelled into the earth and laid out its damp inner parts in tidy layers like sedimentary rock, each layer a slightly different tone of brown-black. After the birth, I saw an osteopath who described connecting me back together in slices, like a landscape that had become dislocated. So this painting is also about earth, sustenance, and pigment – thinking of how Rembrandt ground his own colours.

‘Den or Cornetto’, 2023 – Oil on Canvas, 120 X 100 cm

The tunnel as a constraint on viewing is prominent in ‘Den or Cornetto’. What’s going on there?

I was thinking about dens as in tunnels, and how they might be built. Cornetto could be some version of a cone as used in ice-creams – sharp end, open top; or the cornet instrument, that uses pistons to trap air; or the shape, like a possible puncturing tool. I was thinking about: where do you get your vision? I heard of a writer who eats as he writes so that his gut can play a role – activating an organ to feed his writing as if it were an engine. So maybe the tunnel of vision could be from the mouth, the mouth could be a portal to other realms. It’s a bit sci-fi: could you reverse the seeing process? The eyes are blinded but the mouth sees…

Is there something of a child’s playfulness in that?

As a kid I remember collecting empty toilet rolls to build things with. These redundant tubes, once heavily sellotaped and connected, could morph into limb augmentations, eye extenders and viewfinders, often becoming absurd glasses or rudimentary telescopes. Attaching them to eyes or mouth, sound could be carried further, and it seemed sight could be supplemented. I rehearsed this in the studio with two sawn-off tubular poles I had found. I felt like a horse wearing blinders in traffic, fixed and dangerous, externally oblivious.

Does your baby’s own ‘tunnel vision’ come into the show?

Yes! Early in the pregnancy, I read that the baby has tunnel vision in the womb, and reading about their sight development and understanding of object permanence in science and child psychology reference books is fascinating and very weird. After the birth I was reading ‘Diary Of A Baby: What Your Child Sees, Feels, And Experiences’ (Daniel Stern, 1990) which describes the development of a baby from the baby’s point of view.

Who’s that in the detail from ‘Dogger, Rockall and Malin’?

That’s me inside myself, painting myself with myself (my guts, thoughts, feelings etc). I put myself in a cave, embracing where I was with all these tunnels. It’s a literal depiction of the outside-inside. I did visit some caves and tunnels for real. Stalagmites and stalactites are always crazily lit, so they look toxic. And they look like gut systems…

Installation view with ‘hmeep hmeep’, 2024 Photo: Damian Griffiths (the title comes from how the film’s sound creator, Paul Julian, spelt Road Runner’s version of ‘beep beep’)

You’ve also made a mural that channels another tunnel inspiration from the violent comedy of the ‘Road Runner’ cartoons. Could you tell us about that?

The Looney Tunes cartoons feature the painted tunnel as one of Wile E. Coyote’s stunts to trick the Road Runner. In the episode ‘Fast and Furry-ous’ (1949), Coyote paints a tunnel onto a rock, instantly giving the optical illusion of an open tunnel, then lays in wait for the Runner. To Coyote’s chagrin, Road Runner ploughs on through the imaginary tunnel, confounding Coyote. He then takes a run-up to the painted tunnel and smacks hard into the rock face, bouncing off, dazed and comedically crumpled like an accordion. It’s shocking how quickly you can create an illusion like that, and there’s a slapstick pleasure to it. In March 2016, Yahoo News reported that a street artist had recreated Wile E. Coyote’s fake painted tunnel so successfully that a Fiat drove into the wall on which it was painted!

Recreating Coyote’s tunnel in the studio to better understand it, I appreciated that taking on ‘tunnel vision’ could be a way out of my stuckness, faced with an empty studio – the idea of tunnel vision could become an escape route for me, like Road Runner. The tunnel is based on a screenshot from the cartoon. I wanted the surrounding figures to be spontaneous, to be playing with where things could go, where they could tunnel, and what depth of the tunnelling metaphor I could get away with.

Top Photo: Emma Cousin demonstrating ‘tunnel vision’ © Courtesy of the Artist

‘Tunnel Vision’ runs 18 Jan – 24 Feb at Niru Ratnam, 71-73 Great Portland Street, London W1W 7LP. Cousin’s 2,000-word artist’s statement is available there, and I recommend it for a fuller exploration of all things tunnel vision.

Roland Hicks: Interview of the Month, January 2024 – Paul Carey-Kent

recent years Roland Hicks has used gouache, paper and coloured pencil to refashion and scrupulously reproduce the texture of plywood and Oriented Strand Board (OSB), so that first we are deceived, and then surprised by such an investment of time and effort in what look like discarded offcuts. He sees them as ‘trompe l’oeil still life paintings of fictional artworks’. It’s only at the level of finely graduated detail that we can tell what has been done. In 2021 he won the biennial Evelyn Williams Drawing Award, which sponsors the making of an exhibition at Hastings Contemporary. For that, Hicks has expanded his approach to make a site-specific installation. Two whole sea-facing walls are covered with a patchwork of apparently found materials – ‘The Fourth Wall I’ and ‘The Fourth Wall II’ – while the interstitial window with a sea view hosts two of three ‘Guardians of the Fourth Wall’, sculptures picking up on the materials used to construct the famous fishermen’s huts nearby.

Roland Hicks in the studio with previous works, photo by Laura Wright

How long did the show take to make?

I tried it all out on a wall in my studio beforehand, using the same sort of methods, so I knew the work in theory – but there were two walls in Hastings, both bigger. So most of it had to be done on site over five weeks. I had a couple of weeks before the opening to make one wall, pretty much according to my plans. Then after the show opened, I made the second wall in public, so visitors could watch me. For that, I was happy to let things happen. People engaged very actively, and most were delighted when they found out how the illusion worked. Several came back to track my progress or bring their friends. The Fourth Wall refers both to the literal description of the number of walls in each room, as well as the theatrical tradition of breaking the illusionary fourth wall between a stage and an audience, so I was both building and breaking the fourth wall simultaneously.

Do you think ‘The Fourth Wall’ looks like art – given that you wouldn’t normally expect to find such a mixture of objects?

I’d probably say my separate smaller works tend to look more like art because they’re presented in isolation on the wall in the usual way. I’m interested in at what point something starts to look like an artwork, and what is deliberate and what is accidental in that. Because it covers the whole wall, there’s a suggestion that ‘The Fourth Wall’ might not have another wall behind it, so it weakens the fabric of the building and makes it look shoddy. I started by imagining a fictional creator who wasn’t me – the potential non-art backstory is that these were things that had been found in skips, perhaps, and brought together by a collector here for reasons open to interpretation. There’s more than a hint of folly about both the real and imaginary versions of the wall’s creation.

How have you responded to the site?

There are connotations of sea defence because of the location – the sea could come in. One of the ‘doors’ is the same as one in the gallery itself, so the work refers directly to where it is, as do the ‘Guardians’.

Detail from ‘The Fourth Wall’

You’ve mixed the ‘real’ and the ‘illusionary’?

Yes, it’s the first time I have allowed myself to use real items. That sets up the question of what is real and what isn’t. There are, for example, real door handles. But all the tape and rust effects are illusionary. The rust was very much informed by spending time in Hastings, where the sea air makes any metal rust, and stains the buildings. I found a way to recreate that with chalk pastel. That’s an ageing effect, though, of course, it isn’t old. And the whole arrangement isn’t meant to look as if it’s been there very long, more as if it’s been made from elements which have been thrown out from elsewhere. There’s a suggestion it isn’t finished, as where there’s an unused reel of (unreal) gaffer tape…

Is that a moth towards the top?

I did that because a real moth landed on my studio mock-up, and at first, I thought ‘Hang on, what’s that?’ Then I thought: ‘I didn’t do that, but I really should’ – and so I did!

Is your main purpose to make us wonder what is real?

All illusionistic art involves some kind of deception, and I’m interested in how these walls are effectively built from misinformation and misdirection. But the guessing game of trompe l’oeil can fizzle out once you’ve got it. So I try to find a balance by keeping other questions open.

What are those other questions?

I like to play with the degree of spontaneity, to take something that looks as if it’s been put together quite quickly, then slow it down so it takes a long time to recreate it. I’m also interested in the point at which the art happens, in confusing that moment. In a way it messes around with time, so that a fast creative thing and a slow creative thing happen at the same time. Time becomes elastic – you’re not quite sure where the moment of creativity is located. That leads to the question of how much aesthetic decision-making is intentional – what if you make the considered look accidental? Interesting things happen when you roll those two things up against each other.

‘Guardians of the Fourth Wall’ (Detail)

Might we also read the work politically?

Certainly, building walls at a border location brings in possible issues around migration or climate change. Or it could be shoring up a cultural institution against hostile opinions. The apparent poverty of materials used and precarious, the makeshift appearance of the work could be read as a metaphor for other kinds of social fragility.

Do the whole walls also operate as abstract paintings?

I aim to find a balance between an abstract painting and an accidental cobbled-together thing, without settling too clearly on either side. If it starts to become too knowing a reference to a particular type of abstraction, I’ll try to pull it back a bit. There are hints of Piet Mondrian, or Victor Pasmore – whose 2020 retrospective was the first show I saw at Hastings Contemporary. That’s hard to avoid in presenting constructive geometric elements. The other echo is of how Kurt Schwitters incorporated what look like found bits of stuff into his Merzbau. In 2017 I curated a show in the Lake District at his Elterwater Merz Barn (1947-8).

Did your curation pick up themes present in your own work?

Yes, that was titled ‘Humble as Hell’, and included some work which you might think is just an insignificant thing with no artist behind it. Is such work a humble and Zen-like contemplation of everyday ephemera, negating the artist’s ego? Or does it take a rampant ego to think it can transform bits of rubbish into creative gold? My works are probably a bit of both in some ways.

Detail from ‘The Fourth Wall’

How do you relate to the notion of truth?

I’d say I have a committed but slippery relationship with the truth. I curated a show called ‘The Tiresome Truth’ (at ASC Gallery, London in 2019). That asked whether there is more honesty in allowing materials to just be themselves than in simulating them faithfully – does the deception in that rule out the truth? Picasso said that ‘art is a lie that makes us realise truth’.

But ‘truth versus fiction/realism versus deception’ is just one of several points of balance in your works.

Yes, you can also ask if they’re painting or sculpture, still life or abstraction, accidental or deliberate, fast or slow, playful or serious, ugly or beautiful, old or new…

Roland Hicks: ‘The Fourth Wall’ runs to 3 March at Hastings Contemporary. Hicks will be in conversation at the gallery with Graham Crowley, winner of the 2023 John Moores Painting Prize, on 2 Feb.

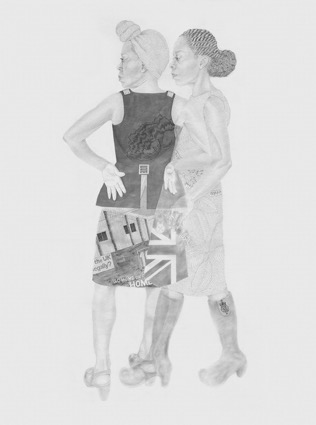

Paulina Olowska: Interview of the Month December 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

Multi-media artist Paulina Olowska has said that what fascinates her the most is ‘the non-linear history hidden beneath the surface’ and that growing up in the 1980’s ‘amid two opposing visions and mentalities in socialist Poland and the United States’ significantly shaped her artistic outlook. That has led her to engage with the political and social histories of Eastern Europe and America – most often in the context of female perspectives and narratives – and to investigate how they feel in the present by revisiting them through her work. Her new show ‘Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas’ recasts her interests in the context of natural landscapes and Slavic myths. It incorporates work developed for her major solo show ‘Her Hauntology’ at Kistefos Museum in Norway, and fills the whole of Pace’s extensive London gallery until January 6.

You show five videos of ‘Mamunas’ and ‘Garden Mules’? What are they?

A mamuna, literally translated from Polish as strangewife, is a female swamp demon closely associated with rivers, streams, and thickets. They appear in various forms in folk stories across the Slavic region, and contrast interestingly with the mythologies of Christianity which we all know. The ‘Garden Mule’ is the white little boy with horns: that name came out of my discussions with curator Kate Smith when we were filming in Norway. After telling her what mamunas are, I said: ‘let’s make up some other names of deities from the forest’, and she suggested ‘garden mules’ – it sounded good and I like it that the mule lives between animals, being half-horse, half-donkey, so it’s a metaphorical title.

Paulina Olowska: detail from ‘Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas’, 2023 – five channel framed video installation, dimensions variable

So we have four mamunas and the garden mule. How have you presented them?

Making a show in the middle of the woods in Norway, was as inspiring as running a foundation (Artist House Kadenówka Foundation) in the middle of the countryside in Poland. Both are surprising and unexpected locations to present contemporary art. To amplify the spirit of the Museum in Norway, in what is called ‘The Twist’ – a twisted building over a river – I decided to add more fake trees inside and place the Mamunas videos in the hollows of them. At Pace they are on screens set in carved frames like woodland hollows. I love making amplifications of spaces, as in the performance The Mother in Tate Modern in 2015, where I created set of a Huculian hut with paintings by Pablo Picasso , Meredith Frampton and Henri Matisse.

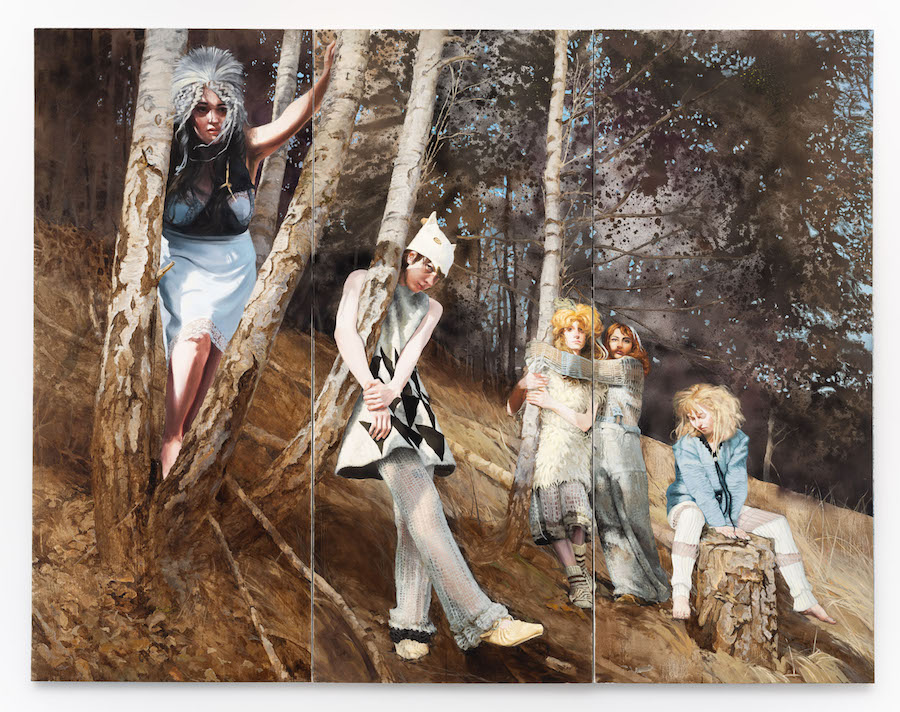

Paulina Olowska: ‘Dziewannas (After Branislav Šimončík)’, 2023 – oil on canvas, 310 x 209 cm

Several large paintings feature the same cast, but others – such as ‘Dziewannas (After Branislav Šimončík)’ don’t. Why is that?

Most of the works come from my photoshoot and films made in Norway, but I wanted to take this show beyond just those ideas. So others, like Cepelia, Dziewannas or Glisne are paintings based on found photography that I reappropriated with a more personal narratives. For example I found these amazing portraits of a young androgynist couple on an oak tree in recent Vogue Czech shoot by Bransilav Simoncik. I present them as Dziewannas, the wood demons, as archers guarding the forest – the arrows are my addition.

You show your studies for the costumes in which the mamunas performed, and also puppets wearing the costumes. I guess that fits in with your long-standing interest in fashion?

Yes, I love to connect art with fashion, and for two years I worked as artistic director of Polish Art Vogue: I did photoshoots, met models, saw the industry. A lot of my work comes with the belief that fashion is a metaphor for personal and social revolution. Pose and hair style become symbolic. And the parallels and differences from art were fascinating for me. Fashion deals with theatricality through colour, form, space, people… I started to look at fashion photographer’s portfolios and find the images which resonate with me. I often create outfits for my models, as in the downstairs space of Pace, where I include the outfits from the photo session in Norway.

Paulina Olowska: detail from ‘Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas’, 2023 – five channel framed video installation, dimensions variable

Who are the mamunas?

Mine are mystic creative professionals (laughs)… While at Vogue I met a lot of incredible people working in fashion. One of them was Lou, from ‘Let it go’ agency in Amsterdam. Lou was managing talents such as Amy Morgan, Rick Geene, Sayuri Chetty, Kamil Sznajder and Yasmin El Yassini…. They are my muses – my mamunas and mules. They’re all in their twenties, they do part time studying while modelling or being actors or musicians. Filming them was great fun.

They seem more mischievous than demonic?

One thing about demons is that we’re scared of them, and their power, so if they’re too friendly it’s not good! But what is true about Slavic goddesses – as well as Hindu goddesses – is that they have their yin / yang virtues, their either / or, the friendly side covering the more evil side.

Paulina Olowska: ‘Strzygla with Mamunas’, 2023 – oil on canvas, 260 x 333 cm

How were the paintings of the five characters – such as ‘Strzygla with Mamunas’ – made?

The idea was we met to make films in the tree hollows, but I grabbed Kacper Kasprzyk, the photographer, and Monika Kucel, who helped me make the outfits, and we had a photoshoot day outside. We did plein air photos, middle of the winter with Mamunas exploring the rivers and forests of Jevneker village in Norway. It was spontaneous – and I’ve found that spontaneity works well for me. I was looking at them throughout the year, left them on my studio wall, I thought ‘they are excellent, I want to make paintings from them’. Then I took the time to explore in my painterly head how to work with paint gesture and weave in the painting the expression of nature. And I liked the connection with how back in the day painters had an entourage – models, assistants, students – always this aspect of the artist being present with others – now I feel painters are more solo in the studio, so the idea of recreating images from my tableaus was special. And the mamunas have come to the openings…

Why not show the photographs?

Perhaps I will get there, I am interested in exploring the language of photography, but at the moment when I reflect on the photographs, I feel a desire to transform them into a deeper visual language, echoing the moment. Photography is a split second while painting is a duration, a constant re-entrance into the scene, a mind game, a kind of head projection combined with the alchemy of the process. A painting emerges from months of being with the image in the studio – I really like painting as a method of mediation. My aim is to achieve what Bernard Frize, one of my teachers, called the ‘economy of painting’ – how to represent an image with the most persuasion in the gesture. In this show, inspired by Norway and seeing the divine nature painting in its new National Museum, there is a new direction for me in the representation of nature. I like to have question in mind when I make a show, and here it was not so much Slavic folk art as ‘how do we represent the landscape as a painter?’ And so with every image I moved between different approaches and techniques.

Your previous work has often reinterpreted historic female muses for modern times, and you’ve spoken about how the past haunts the present. Could you say something about that and how it applies in this show?

Here I’m looking to research the missing links to modernity not through historic muses, but through folk art. That’s an alternative setting for the theory which dear Mark Fisher developed to apply to music, in which elements from the past persist in the manner of a ghost. His approach made sense of my take on feminism – can you make a new future for feminism through figures from history coming back to you, by re-envisaging them for what they can give us now? That’s why my book of the Norwegian show is called ‘Her Hauntology’ – as it’s my take on it.

Top Photo: Paulina Olowska: ‘Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas’ Costumes’, 2023 – costumes, wigs and mannequins – dimensions variable

Paulina Olowska: ‘Squelchy Garden Mules and Mamunas’ runs Nov 22, 2023 – Jan 6, 2024 at Pace Gallery, 5 Hanover Square, London

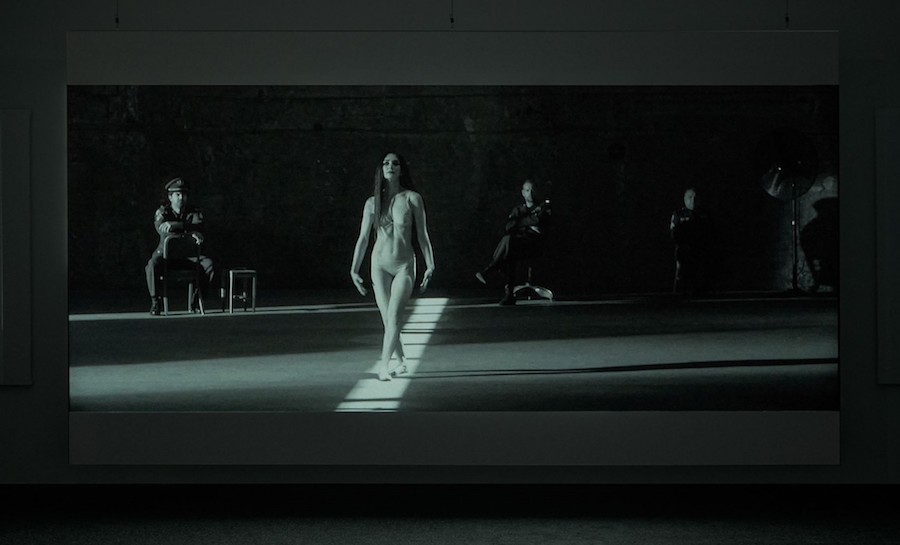

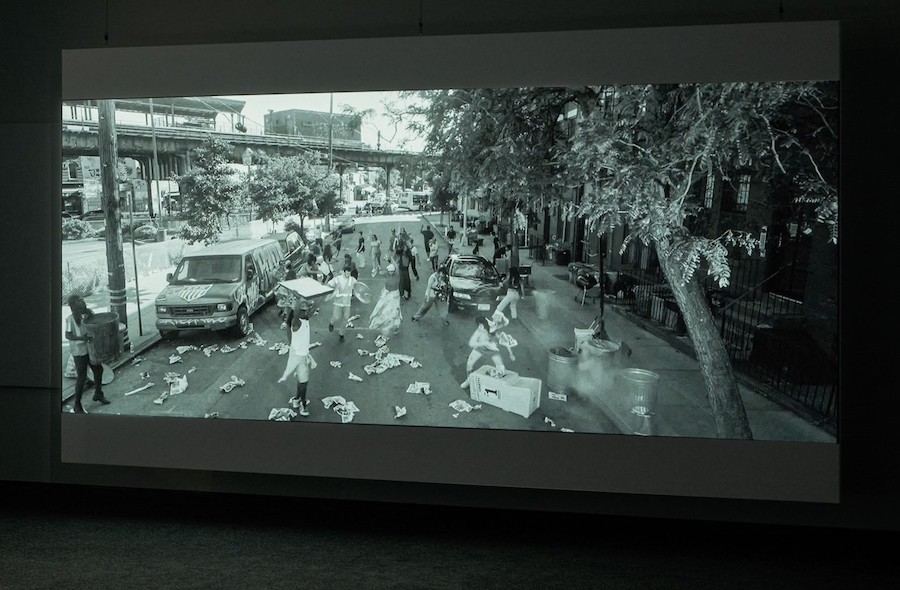

Shirin Neshat: Interview of the Month, Oct 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

I talked to New York based Iranian artist Shirin Neshat in her current show at Goodman Gallery, which presents an immersive video installation and a series of nude portraits considering the female body both as an object of desire and as an object of violence and shame. In the chilling 15-minute double-screen film work ‘The Fury’, Neshat’s protagonist dances seductively for a room of impassive soldiers. Then we see bruises on her body, indicating the abuse she has suffered, followed by her emergence onto the streets of Brooklyn. Physically displaced and mentally disturbed, she walks the streets reliving the horrors of her past. From the street’s vantage point, she is one among many in her cocoon, alienated and atomised. Yet, at the film’s conclusion, she sparks a mini-revolution as women throw trash into the air and dance wildly.

How did ‘The Fury’ come about?

For some reason, I got drawn into following the trial of the notorious prosecutor Hamid Nouri, who was captured by luck in Sweden by the international court. He was among those responsible for the massacre of nearly 3,000 young political prisoners in Iran. The victims’ families, who are now living outside, came to give testimonies. What struck me the most was how the regime would rape the young women before execution because, according to Islamic laws, virgins cannot be executed. I couldn’t stop thinking about these incredibly horrifying reports. I’ve also known several Iranian women who have spent time in prison and heard their stories about women who are sexually assaulted in prison and how they could never recover. They would often sit in a corner, wouldn’t speak, and many would commit suicide after they were freed. So, the concept of “The Fury” developed during 2021-2022, and I shot the video in June of 2022 before the Woman Life Freedom movement in Iran. In this highly fictionalised and stylised narrative, the female protagonist cannot disconnect from her haunted past and her psychological trauma, even in the state of freedom in a new country. I wanted to make a work which draws this boundary between the interior of her mind, the exterior of her mind, the interior of her apartment, the public space – and how everything was disconnected – like she wasn’t present till the end until she was most vulnerable and asked for help. So everything was created around the notions of sanity/insanity, illusion/reality, interior/exterior, Iran/USA.

And the setting is personal to you?

This video was shot where I live, in Bushwick, Brooklyn, a working-class, primarily Hispanic community. Most of the neighbourhood barely speaks English, yet these are the people I am closest to and see more than anyone else. They are my community in New York, even if we all come from different cultures and religions and speak other languages. I feel safe and at home here.

Is the woman based on an actual person?

No, she’s a fictionalised character I created and is not merely meant to represent a female political prisoner in Iran but to capture some of the trauma and dichotomies experienced universally under such conditions.

You use a double-channel video. What is the advantage of that?

This video wasn’t designed initially in two channels; I decided on that later. Everything became about creating two different points of view and putting the audience in an uncomfortable position. So, in a way, the audience becomes the editor, deciding where to look and how to put the story together. I wanted the audience to distinguish between the way she viewed the world and the way the street bystanders and the uniformed men viewed her.

She begins in a seductive manner. Why is that?

There is a development in this short narrative. First, the female protagonist appears as an object of desire through her erotic dance, and then slowly, we reveal the brutality of what has happened to her. She’s at first seductive because that’s often the story of women: we have the power to seduce and create temptation, yet due to the same reason, we can fall victim to violence. This subject is not exclusive to Iranian women, of course – I am a firm believer that most women around the globe have experienced some form of sexual assault or molestation at some point in their lives, but they don’t talk about it. We tend to internalise such experiences and even become ashamed of ourselves and our bodies.

And that’s picked up in the poems on the photographs in the show?

Yes, the poems I transcribed on the surface of the photographs are from ‘Another Birth’ by Forugh Farrokhzad, who died in 1967 at the age of 33. I have often used her poetry in my photographs. She was one of the most radical among Iranian women poets in how she expressed the problematics of the female body in relation to traditional and religious values – taboos. Her poems have often been considered blasphemous, and at some point, her books were banned in Iran. I remember one of her poems. I believe it was called ‘Face to Face with God’; she poses the question to God: if you are the creator, why am I supposed to feel so much shame about a body that you’ve given me?

Unusually for your work, both the film and the photographs feature women naked or near-naked. Why is that?

I couldn’t imagine the depiction of sexual exploitation without showing the naked flesh of a woman in “The Fury.” In the video, it was necessary for me to show both the seductive and yet brutalised body of a captured woman. In the photographs, I tried to take a similar approach. Some images resonated with notions of power, pride, dignity and beauty regardless of the women’s size and age – and in other images, we are faced with women in pain whose bodies have obviously been brutalised.

What led to how do you show the men?

The men’s gazes expressed everything: the sense of hate and violence. I didn’t need to show them doing anything to her; their bodies and uniforms represented their power and control over her. The interesting thing is that their blank expressions never changed from the time she dances seductively to when she finally fell to the floor bruised. They remained emotionless, which is so typical of men who are incapable of humanity-only atrocities. I hate to say it, but some people enjoy other people’s suffering. I’m an optimist and would like to think there is a good side to every person, but you just have to look at the last few days in the Middle East to see how hatred, violence and evil are so deeply ingrained in people. When she’s on the floor struggling, you see the men looking at her as if they enjoy it. Lastly, I was careful to make the uniforms generic and not specific to any culture.

Why is the whole show in black and white?

Initially, we shot the video in colour, but later, I changed my mind. I think there is a severity in black and white that felt right to my narrative. Also, we occasionally used Infrared with the camera, which turns everything into negative, and that was used each time we went to her point of view on the streets. Overall, I felt that the black-and-white look also helped with the melancholic mood of the story. I slowed down music – a Persian song with lyrics rewritten in Arabic – to make it more melancholic but also beautiful. That goes back to the mysticism in Iran – things are terribly sad and emotional but highly beautiful and affecting.

You made the film before Masa Amini was killed, yet there are echoes?

It’s almost uncanny how the story of “The Fury” is similar to what transpired in Iran a few months later. Here, we have a woman who becomes a victim. Her victimisation unleashes other people’s rage, which culminates in a protest, and that is exactly what happened in Iran: a revolution unravelled immediately after the murder of an innocent woman, Mahsa Amini, who became the victim of the Iranian government.

Dance is important in the film?

Yes, dance is central to the film, both as the female protagonist danced for the uniformed men and how, in the street, bystanders turned their protest into a strange ritual of dance and destruction. Oddly enough, during the Woman, Life, Freedom revolution in Iran, dance, which is forbidden in public, became an expression of protest as well.

Top Photo Shirin Neshat: The Fury – installation view, courtesy Goodman Gallery

Shirin Neshat’s ‘The Fury’ runs to 4 November at Goodman Gallery, 26 Cork Street, London W1S 3ND

Ghislaine Leung: Interview of the Month November 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

Ghislaine Leung is one of the four artists nominated for this year’s Turner Prize, the winner of which will be announced on 5 December.

Her show in Eastbourne consists of ‘score-based’ works: they repurpose found objects, but Leung’s parameters for how to show them leave plenty of scope for the hosting Towner Gallery to influence the outcome. That relinquishing of control allow the socio-political and spatial conditions of art production, its presentation and re-presentation, to come to the fore. That may sound worthy but potentially dry – yet Leung goes about things with an appealing wit, and the results are compelling in themselves.

As explained in detail in your recent book ‘Bosses’, your starting point is how to make work rather than what work to make?

Yes, I aim to work with what I have, rather than what I don’t have – it’s untenable trying to work with what you don’t have, which is the position faced by many artists who can’t access the resources they need – which, of course, also exacerbates existing class, gender and racial hierarchies in our industry. I was interested in finding a mode of production that made space for a different kind of work. And this came from something I probably initially conceived of as a problem, I always thought you can make an artwork and you can perfect it in some way yourself. And then the work goes into a context that you can’t control and it has a different read or it changes or it shifts, and this was something I wanted to control. It was the wish to control that seemed like a clear problem to me. I wondered how to embrace the contingency of works instead, to embrace their vulnerability. Rather than thinking ‘how can I fix and control this? How can I maintain its integrity in the way that I have conceived it?’ I shifted to thinking that the resilience of the work could come from its vulnerability, its total contingency, its complete dependency, my trust in a situation.

Is that in line with Sol LeWitt’s approach as set out in ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’, 1969, such as ‘Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist’s mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly’?

I’d see my work as more of a dialectical flip on LeWitt’s methodology. He starts with concepts which lead to the material form. For me, materials, inclusive of the sets of conditions and limitations I’m working with, are generative towards concepts. I don’t know the final form, and – given the highly contingent nature of the scores – I can’t and, in fact, don’t want to. This is why the works are scores rather than instructions, just as a musical performance isn’t quite the composer’s or the performer’s. In that sense, I am theoretically the composer, and the institution is the performer, and the work, in each iteration, comes from both. I like to be surprised by my work when I come into a show!

Ghislaine Leung: ‘Violets 2’, as installed at Simian, Copenhagen – GRAYSC Images, courtesy the artist & Simian

Can you say something about the largest work in your Turner Prize display?

The score for ‘Violets 2’ reads: ‘All parts of a ventilation system removed from Netwerk Aalst Bar during its 2017 refurbishment are reinstalled within the space of the exhibition and fixed on the floor. Using as much of the material as possible while keeping it all interconnecting. Spare pieces that do not fit this configuration are bracketed together in smaller formations. A welcome sign is installed.’

I was working there in Belgium from 2017-19, and we were thinking about who the institution was speaking to – about how often ‘the public’ is referred to like a separate and somewhat mysterious entity to be spoken to or placated. I was aiming to bridge this externality by thinking about the internality – the politics of the institution and my position in that – an immanent form of critique looking at the structures of power inside, rather than outside, the place. What about the people already in this room, the politics that are already here? So how the institution was organised in both social and physical structures. So many of the circuits of power, the things that allow for the functionality of the building, are rendered invisible. At the time, the institution was undergoing a renovation and discussing what was going to be removed and what was going to be inserted. The ventilation system that makes up ‘Violets 2’ was going to be removed as smoking was no longer allowed in the building, which made it surplus. And I was interested in what these forms of institutional waste were, who and what was considered valid or useful within these public-facing spaces. I took the ventilation system which had been on the ceiling of the bar, and mounted it on the floor of the gallery space above that bar, which had the same spatial footprint. And installed a welcome sign alongside it. I’m always interested in this institutional welcome, on who is being welcomed and why, especially in how ex-industrial spaces become art industrial spaces. Violets 2 has been on almost permanent tour since 2018, it flexes to fit into different spaces, and it shows something different about these spaces each time, as its parameters are shaped by these limits.

Ghislaine Leung: ‘Violets 2’, Towner Gallery, Eastbourne – Angus Mill Photography

You’re asking one institution to do something with another institution’s structures?

The way an institution performs a score says a lot about them, e.g. their Health and safety rules, what they want to achieve – that was my aim at that time, to acknowledge the systems of the institutions.

The sculpture we see reminded me somewhat of the 1960s ‘Square Tubes’ of Charlotte Poseneske – another artist who emphasised the cooperative aspects of her work.

Yes, and I think this is exactly what I mean about how materials can be generative. This becomes especially interesting in relation to historical artworks that refer or even enact forms of industrial production like Poseneske’s. What happens if you use existing industrial objects rather than fabricating them? What shifts what doesn’t? In a way, I’m trying to take something back into the use of art and to understand that as already an industrialised social structure, one that is often unacknowledged but shapes so much of what constitutes not only the art object but who can and can continue to, make art.

Why does the title refer to violets?

I had been thinking about how systemic prejudices are so often perpetuated by our own internalised ‘micro-violences’ that we do to each other and also ourselves. Ones that are fabricated into the internal structures of our institutions. And was struck by how close the pretty and flowery word ‘violets’ is to the loaded term ‘violence’.

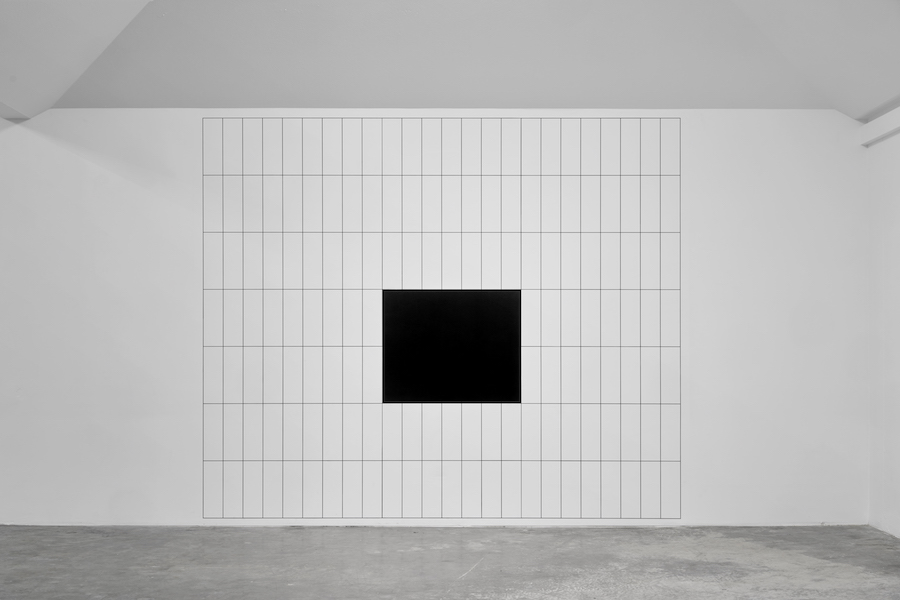

Ghislaine Leung: ‘Hours’, 2022 – photo Paul Carey-Kent

‘Monitors’ broadcasts a baby monitor from one room to another, and ‘Hours’ divides the week between your studio hours, indicated by a Malevich-like black square, and the rest. I note you spend only 8% of your time in the studio – presumably, you’re constrained by factors such as being a mother?

Yes, being a mother, and working, and in multiple jobs. I think the earlier works like ‘Violets 2’ and ‘Public Sculpture’ were very much about institutional systems, and how they constitute the work, what their labour conditions are, how they work. In the past few years, especially since having a child, I’ve become more and more interested in how I work, how I have internalised various expectations and ideas about labour and value; questions that are about how I institute, and taking a position of critique into a more reflexive and lived form of actionism. As such the more recent scores have become less about the interrelation between two institutions, and more about my form of instituting, how my labour, life, limits, collide, are in conflict or grow… about that intra-institutional aspect of bringing myself in. For many years I felt I couldn’t do that, felt that how I lived didn’t have enough value to speak about, but more and more I feel that speaking about that situation is a necessity. And if you’re trying to make work inclusive, then life is really important within the work.

Ghislaine Leung: ‘Public Sculpture’, 2018 – Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

‘Public Sculpture’ presents a group of toys from the collection of the public library in Reading. They struck me as unusual toys?

They are fascinating, yes. Toy libraries often have a lot of these kind of role play toys, leading to questions about what roles we play, or the roles played in the construction of such roles. And there are two companies – Theo Klein in Germany and Casdon in the UK – who specialise in miniatures of branded goods, so you’ll get a Theo Klein Miele washing machine or a Casdon Henry Hoover etc.… I was interested in that double identity – in that one object has two brands attached. And the toys have another double identity: as individual objects they are toys in the library; as a set of objects, they are a loanable artwork by me. Both exist in the library system, and you have to join the library to access them, either way. So I’m interested in how the work circulates as well as how it is actioned through the score. And this doubling – or troubling – of identity is important to me, as a mother and an artist, as someone with a father from Hong Kong and a mother from London. I’m asking what identity is if you think of it as not so much as the objectifying question of ‘what you are’, but ‘how you are’.

Work by the four artists shortlisted for the Turner Prize 2023 (Jesse Darling, Ghislaine Leung, Rory Pilgrim and Barbara Walker) is on show at the Towner Gallery, Eastbourne to 14 April 2024. The winner will be announced on 5 December. Ghislaine Leung was nominated for her solo exhibition ‘Fountains’ at Simian, Copenhagen.

Top Photo: © Artlyst 2023

William Cobbing: Interview of the Month, September 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

William Cobbing has three shows opening in September: he’s in the group shows ‘After the Performance’ (with the film ‘screensaver’ at Tension Fine Art, Penge 7-30 Sept) and ‘Full House’ (ceramics including ‘Float’, presented by Canopy Collections at Cromwell Place, South Kensington 14 Sept – 1 Oct) and has a solo show at Airspace Gallery as part of the British Ceramics Biennial in Stoke (23 Sept – 5 Nov), with a series of new videos, sculpture, and performance, exploring a playful and ambiguous interaction between people immersed in mounds of formless clay. ‘These earth-clad people, says the press release, ‘are caught in an ouroboros loop of transforming themselves’ and ‘individual identity is effaced, with the protagonists becoming hybrid forms somewhere between themselves and the material’. It seemed a good time to talk…

‘Will.ni.naiz’, 2022 – video stills

PCK: You might say that clay is foregrounded in your work performatively, in a more radical way than just using it to make ceramics. What’s the appeal?

WC: It’s the clayiness, the clagginess, the tactility, the squelchyness of clay I like to work with before it turns into beautifully honed pots. I’ve been reading Petra Lange-Berndt’s catalogue essay for the exhibition I was in: ‘Further Thoughts on Earthy Materials’ at Kunsthaus Hamburg. She examines creation myths, as in the bible, in which clay is a passive material that gets shaped and always with a gendered contract that man has autonomy over the material. She looks at the feminist critique of this, in terms of ‘material’ signifying ‘mother’, subverting Western ideas that material is passive and needs to be conquered, with clay having its own innate qualities, its own personality. That also made Lange-Berndt think of Kazuo Shiraga’s, ‘Challenging Mud’ (1955), in which he wrestled mud with the lovely takeaway line ‘and the earth won’. I’m also interested in the Jewish myth of the Golem, in which once the Golem is formed, a ‘shem’ is put under the tongue, and that gives life to the clay. It’s a mutable myth, but there’s a 1915 film ‘Der Golem’ in which the Golem, created from clay, rampages through the streets, out of control – the myth of decisive agency over material is countered.

Still from ‘screensaver’, 2022

Do you also associate your work with the environmental agenda? ‘screensaver’ might be seen that way?

Yes, ‘screensaver’ shows an expansive clay ground of which we are a part, as opposed to being separate from it. There are no digital interventions: it features four performers, directed by me with no special effects – what you see is what you get. And it suggests that the world can cope without us, in contrast to the humancentric idea that the world in some sense can’t exist beyond us. It can, which is humbling. I also think of how Georges Bataille, in ‘The Big Toe’ (1929) explains that ‘the function of the human foot consists in giving a firm foundation to the erection of which man is so proud (the big toe, ceasing to grasp branches, is applied to the ground on the same plane as the other toes).’ Yet even though the big toe is central to the human as vertical and separate from the earth and looking towards the heavens – we have our feet in the mud…

You could look at ‘screensaver’ as a dark work, as if for example an earthquake has just occurred. But the hands do also seem to be enjoying the clay. How do you see it?

I’m hoping there is ambiguity in all my videos. They elicit a variety of responses from attraction to repulsion – some people find them abject, revolting, nihilistic. Others find them funny. Here I do also see elements of sensuality with the material, and a reference to the process of making – but without the result. That’s a kind of artistic limbo, so ‘screensaver’ deals with the state of limbo.

The single head video works, made with the constraints of lockdown, have been widely viewed online. They strike me as quite painterly, as the colour bleeds out of, for example, ‘Will.ni.naiz’ (as above)

I did start out painting at school, but switched to sculpture soon after starting art college. I don’t paint now, but I loved Auerbach, Bacon and Guston– who use paint in a visceral way. That slicing away of layers isn’t quite destructive – people saw it as ‘peeling back into the self’.

‘Float XL’, 2023

The ceramic ‘Float XL’ relates to the solo videos?

Yes, it came out of modelling clay on my head, but has a kind of impossibility. I sometimes try to maximise the qualities of each medium, and you can’t separate head and body on film! It’s wanting to draw attention to this poor guy with a clay mass ball for a head. Materiality in sculpture is often about heaviness and gravity, and this is evading the normal physical constraints. The videos are referenced, playing jokily between the rough and smooth clay, by the more realistically sculpted arms. I made this on a residency at the European Ceramics Centre (EKWC) in Oisterwijk, The Netherlands, where I had the chance to work with top technicians. That enabled me to experiment with different effects on clay – the arms use a Chinese celadon glaze, a semi-translucent pale green; the rougher parts are sprayed with an underglaze.

‘Float XL’ might also suggest carrying a rock?

That fits with a view I have of the video heads as a whole as picking up on a possible interpretation of Camus’s ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’ (1942). Sisyphus, in ancient Greek myth, was condemned to repeat forever the same meaningless task of pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll down again. Yet Camus concludes: ‘the struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’ A daily repeated routine can give a sense of meaning, as opposed to seeing that only in the achievement of a final objective. Being engaged in a process can be engrossing.

Top Photo: Still from work-in-progress (2023)

You will be showing eight new films in an immersive installation in the appropriate location of Stoke, the historic home of the ceramics industry. Like ‘screensaver’, they feature more than one performer, as indicated by the exhibition title ‘Social Substance’. What are they about?

They return to my pre-lockdown consideration of inter-relationships, and what happen when communication – or miscommunication – occurs. I’m not one for dramatic renderings in my own performances or when directing others: I try to keep actions very rudimentary, almost underperformed, deadpan – with the idea of pulling back, allowing the clay to have more of a say. And almost like an animal movement, here perhaps a bear with big paws.

The performers’ senses are restricted. How does that play out?

I want to think of actions that put obstacles in the way, slow down the movements, and make us think about the restriction of senses, especially on sight. And there’s a difference between viewing the films and experiencing them as a performer. The performances are short enough not to be too claustrophobic, and it becomes quite meditative when you can’t see. The attention given to sight, which tends to be seen as primary, reduces and you then get an increased awareness of touch and hearing – the pecking order of the senses is changed. I’m happy that some people will think it looks horrendous and suffocating while others see it as meditative and sensuous as well as abject. And it’s physical, slapstick humour. People have a particular taste for humour, so not everyone will find them funny, but I see humour as a lubricant to help process more difficult emotions.

You can follow William Cobbing’s work via his Instagram @william.cobbing. His three shows are at Tension Fine Art, Canopy Collections at Cromwell Place , and Airspace Gallery.

Nick Hornby: Interview of the Month, August 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

You will soon be able to follow a London trail of three major public sculptures made by Nick Hornby. As he explains, ‘they have the guise of tradition but are, in fact, far from traditional: they unravel tropes of the monument, but in a way which is accessible and, I hope, not too didactic. I want the viewer to be in conversation with these forms, to feel they are in on the question.’ It seemed a good time to talk to Hornby in his London studio.

You’ll shortly have three permanent public sculptures in London as well as one in Harlow. How did that come about?

In the 2010’s I was shortlisted for several commissions, but lost out to more established artists. In 2019 I won my first public commission. My somewhat cheeky pitch was to say: you’ve just had proposals typical of the main options for a public sculpture – a man on a chair and a shiny blob. The first, a memorial, may be accessible to the public but is deeply problematic, stumbling on critical questions about who is being represented and by whom. The second, an abstraction, avoids those pitfalls, but at the cost of being ‘just another of those’ kinds of nonspecific abstract sculpture. So I suggested we present that dilemma as a question – by taking Michelangelo’s ‘David’, the apotheosis of human perfectibility, and intersecting that with an abstract line from Kandinsky, one of the first artists to set out “theory” behind abstraction. That intersection became ‘Twofold’, in Harlow, Essex. Completing that sculpture made a huge difference: once I had shown that I could be trusted to deliver a massive and structurally complicated public sculpture, I was quickly shortlisted for three other commissions – and won them all.

We can already see ‘Power over others is Weakness disguised as Strength’ opposite St James’s Park tube station and ‘Here and there’ close to the Albert Memorial. ‘Do It All’ will be unveiled in Kensington Gardens on 27 September. What do they address?

The first critiques the trope of the equestrian statue, the second deals with the monumental figure in the urban landscape, and the third combines the silhouette of the Albert Memorial with the profile of Nefertiti, perhaps the most powerful woman in ancient history. Collectively they pose the question: what does a monument mean in the 21st century? Each sculpture asks that question from a very particular site, and embodies my enduring interest in form, material and objectness.

How do they emerge from your long-running sculptural concerns?

From 2010 onwards, I devised a system for intersecting components from multiple trajectories. The method creates new, synthetic forms, but from certain vantage points you can still see the original elements. There is a strangeness to this relationship between the new object and the quotations.

How does ‘Power over others is weakness disguised as strength’ operate?

The artwork responds to its surroundings —Westminster, a national seat of power, where sculptures of men on horseback are numerous. But if those statues celebrate power, this sculpture challenges it through two visual quotations. The first references a statue located outside the Palace of Westminster. On that site there’s a nineteenth-century celebratory depiction of Richard I, unveiled during a period of Industrialisation and Imperialism. The second is a reference from Laurence Sterne’s experimental novel ‘Tristram Shandy’. In the book, a curling line suddenly interrupts the printed text. It describes a conversational gesture, where the speaker waves his stick in the air to describe the experience of freedom. The line escapes the confines of words and embodies the freedom it describes. The presence of that line in this sculpture invites us to think about storytelling, history and the fictions that support the figures we turn into statues. If this sculpture repeats the image of Richard I, it is to suggest the fragility of power and its monuments. After all, he is only visible from certain angles. From others, the image collapses: the figure of power is toppled within his own statue.

Nick Hornby: Power over others is Weakness disguised as Strength, 2023, © Nick Hornby Studios

And the title – a quote from Eckhart Tolle – points towards that meaning?

Yes—in the public realm, I really wanted to avoid misinterpretation: this is a critique of the equestrian statue format, rather than a celebration of Richard I. To shine a light on this subject, I had to incorporate an image of the very thing I’m trying to critique. This is a conundrum and I was sensitive to the fact that you do clearly see his image at a certain point – so I wanted to make it abundantly clear that I’m trying to propose an alternative, and not celebrating military men on horses.

So there is a collage of timelines?

My relationship to time is very flattening – things like love, betrayal and sex are timeless, and you can access just as much truth in something from 500 years ago as today. So here I combine several times into a sort of flat object: a 12th century king, a depiction of him from 1850, a line from Tristram Shandy (published in 1759), and a title from 1997, all in a 21st century sculpture.

Nick Hornby: Here and There, 2023, © Nick Hornby Studios

What comes together in ‘Here and There’?

The same line from Sterne – a thread between the sculptures – is combined with the 1818 figure of the Wanderer from Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting. The sculpture is very close to the Albert Memorial, which in turn connects it to ‘Do It All’. You see ‘Here and There’ first from far down the road, when it looks like a classic monument of man on a plinth, but as you get closer it unravels into Sterne’s line. The Wanderer in the painting is looking out from the top of a mountain, evoking that mixture of beauty, and wonder and fear of the unknown. The painting has become attached to the philosophical idea of the sublime. It’s also strange because we only see back of the man. It’s about presence and distance, and I want to reorient viewer to include the park. There’s also a personal connection: my father has late stage Alzheimer’s, and I am increasingly dwelling on memories. I have exquisitely precious childhood memories of sailing model boats on Hyde Park Pond, when model boats seemed huge and the pond oceanic, so I think that’s where the Lilliputian play with scale comes from.

Nick Hornby: Here and There, 2023, © Nick Hornby Studios

‘Tristram Shandy’ is clearly important to you?

I can trace my practice back to structuralists and the epiphany of reading Saussure, Barthes and Derrida at art school. Tristram Shandy fits with that: it’s non-linear, full of distractions and anecdotes, the first book to make the visual layout of words on the page a component – really the start of modernism. And I love that line for being neither text nor image – not a word, and yet not a drawing.

Nick Hornby: render for Do It All, to be unveiled Sept 2023, © Nick Hornby Studios

Does ‘Do It All’ refer to DIY?

Yes: in 1988 the post-modern architect Ian Pollard designed the extraordinary Egyptian revival Homebase on Warwick Road. It was perfect example of postmodernism – a basic rectangular warehouse with a theatrical cladding. I grew up close by and as a child would regularly buy timber and electronics there. Like tea-drinking, I feel DIY is a classic British institution. Sadly, the building was knocked down but is now the site for a new development and my sculpture. The brief for this commission asked the artists to refer to one of the ten historical figures the new buildings were named after. I was rather shocked to see they were all Victorian men. By chance, Howard Carter, who discovered King Tutankhamun, was one of them, which brought me right back to the mock-Egyptian Homebase that I loved so much. In opposition to Prince Albert, I juxtaposed the incredible and iconic head of Nefertiti. The sculpture’s other component is the Albert Memorial: as a neo-Gothic Victorian monument it has a post-modern quality to it in as much as one period is imitating another. And it is problematic too, with inappropriate depictions from the corners of the Commonwealth around the outside. My goal is to shine a light on contrasting architectural styles and what lies behind them.

Nick Hornby: render for Do It All, to be unveiled Sept 2023, © Nick Hornby Studios

Finally, how are these works made?

The process is incredibly exacting and intrinsically linked to conceptual backbone of the series. Where these sculptures are pitting two contrary images against one another, the mode of fabrication has two distinct steps. The objects are designed parametrically (scripted in code and text), and the resulting 3D object is then digitally flattened into distorted 2D pieces. These pieces are laser-cut from sheet metal (corten or bronze) and then, under huge mechanical force, manipulated from their distortions back into their correct forms, where they are wielded together by hand. The laser cutting is rapid, with pin-point accuracy whereas the manipulation is a slow exertion of huge force. The sculptures are collaborative effort between myself, my engineers (The Structure Workshop) and the fabricator (Benson Sedgewick).

….And the materials?

All three are metallic – two are bronze and one is corten. Bronze is the traditional material for historic monuments and is loaded with history and associations. The equestrian work is in corten – ostensibly a “rusty steel”—which sets up a clearer material distance from the monument being referenced. Corten protects itself by developing a rust-surface, which becomes a protective barrier, like a scab – which is stronger than the original material. What appears to be self destructive in fact creates resilience – perhaps like a self-toppling statue – the fragility is the strength of this sculpture.

Top Photo: Power over others is Weakness disguised as Strength, 2023 – Corten Steel, 5 x 3.5 x 1.3m. Commissioned for Northacre Curated by @nativeartsadvisory. Designed in collaboration with @structure.workshop and fabricated by @bensonsedgwick.@nickhornbyartist.

Here and there, 2023 – Bronze 3.3 x 1.2 x 1.2m. Commissioned by Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Council and the Victoria Road Area Residents’ Association with public art funding from One Kensington Road W8@nickhornbyartist. Designed in collaboration with @structure.workshop and cast by @bronzeagelondon. Curated and commissioned by Ann Elliott

Go to Nick Hornby’s website for more about his public sculptures and his work as a whole.

Mark Godfrey on Alighiero Boetti: Interview of the Month, July 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

Anyone wanting to understand the innovative art of the Italian conceptualist Alighiero Boetti (1940-94) should head to Ben Brown Fine Arts / Claridge’s ArtSpace, where ‘Regola e Regolarsi’ gives them all they need. There are some 90 career-spanning works, informatively presented to demonstrate Boetti’s explorations of serial schemes and systems; his innovative approach to self-portraiture; his use of language; and his way of producing work with the assistance of unknown third parties. I spoke to Mark Godfrey, who curated the Tate’s seminal 2012 survey ‘Alighiero Boetti: Game Plan’ as well as this, the largest subsequent presentation of Boetti in London.

How have you put the show together?

The first room roughly coincides with the world Regola (‘Rules’), and considers the key concepts that Boetti worked with in the first eight years of his practice. It looks quite dry and conceptual, even though it contains a lot of his personal interests. The second part of the show has an explosion of colour and textures, so even though the rules still exist, there is an adjustment to them – Regolarsi means ‘adjustments’. The third space, viewable on request, contains a selection of drawings from his studio. Boetti is celebrated mostly for works operating through some sort of fabrication process. He was, though, the kind of artist who could never stop doing things with his own hands – but he felt that work was very much secret. He would make drawings by experimenting with such techniques as blowing ink, using stamps, or dipping elastic bands in paint and dropping them on sheets of paper. And had his own cosmology of animals which he drew – he liked animals with a great sense of energy and movement.

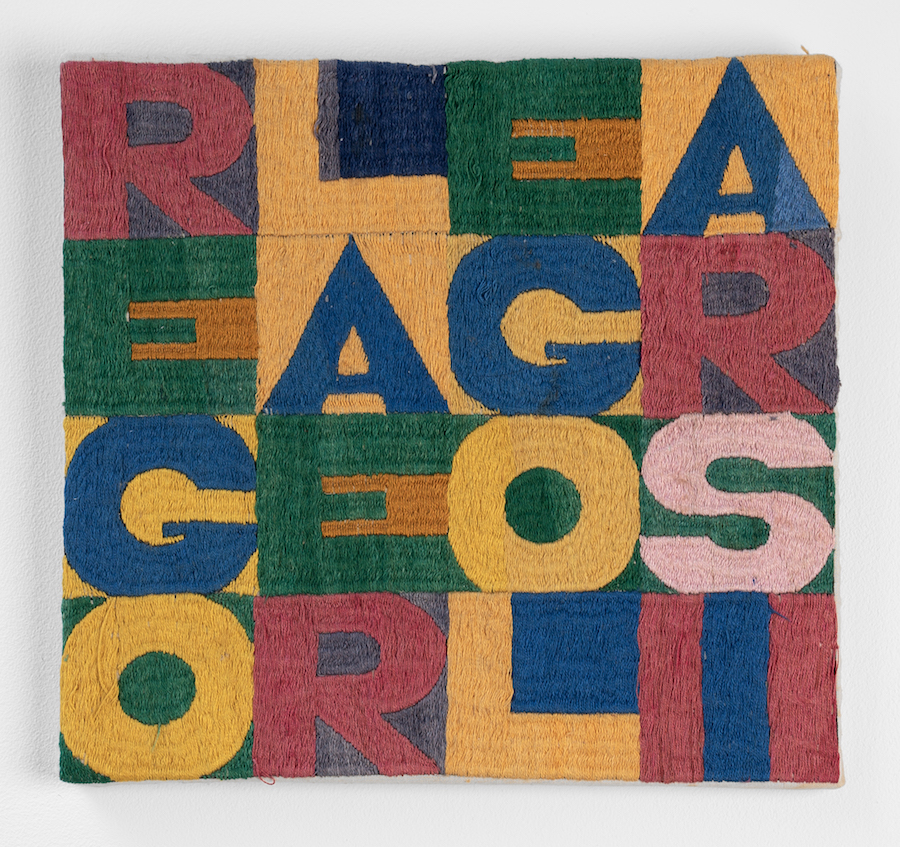

Alighiero Boetti: Regola e Regolarsi (Order and Disorder), 1978 – Embroidery, 23 x 24 cm

How does the word square ‘Regola e Regolarsi ’ illustrate Boetti’s approach?

When it came to embroidery he would write the phrases out and send the canvases off to the embroiderers, initially in Afghanistan, then in Peshawar, leaving the individual colour choices to the embroiderers. They were women commissioned by men, so there was an intermediary between Boetti and the embroiderers. That contrasts with most artists in the sixties: they would either have work fabricated by people that they visited a lot, or might have assistants in their studios – but Boetti set up a system of production whereby people unknown to him completed the work. He liked the idea that the final appearance of the work was as much down to their input as his. The union of order and disorder – Regola e Regolarsi – is something Boetti was obsessed by as a good way of making art. In the word square the order is in that it’s a 16 letter phrase that fits perfectly into a square, and in the fact that every letter gets the same amount of space. The disorder is in the way that the three words are run together, and also in the choice and combination of colours not being controlled by him.

There are several biro works. How do they operate?

Boetti’s biro drawings would be made by students – he worked with a woman in Rome who would commission someone to fill in the biro sheets, so they are anonymous. But they are also eponymous, because they give a sense of the individual draughtsperson’s sensibility. He made up the word ‘ononimo’ – combining the Italian for ‘anonymous’ and ‘eponymous’ – to capture this idea that something was both anonymous and individual. Boetti didn’t know – and didn’t want to know – the people who finished the work for him, and therefore something is left to chance. The show includes an eleven panel biro work using the word ‘ononimo’, which is very lush in its blue. It was made by eleven different people who each took their own approach to the task of filling out the paper. In some drawings, the vertical lines are compact, the horizontal bands are tidy and even and there is little overlap, so there is a consistency of colour. In other drawings, the lines are more dispersed and the bands wavy, or there is more overlap – and consequent darkening. Boetti was able to achieve a real beauty with blue biro which is quite remarkable, given it’s an office tool, really.

Was the number 11 important to Boetti?

Yes, very important: he was interested in pairs and twins – he actually photographed himself as a twin – and 11 was like a twin but with internal difference, as one of the ones has a value of one, and the other has a value of ten. That’s why there’s an eleven-part Ononimo work.

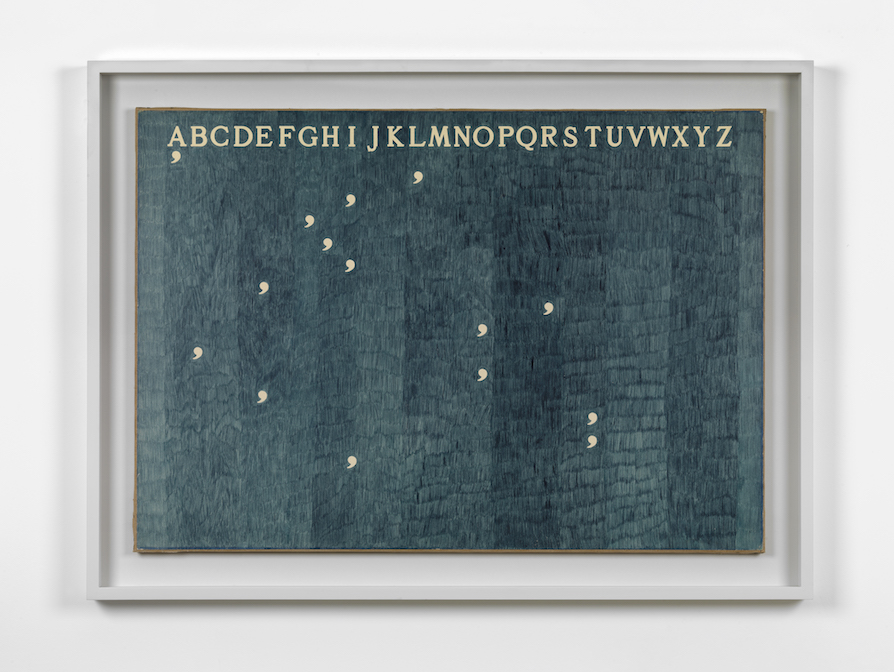

The biro works often feature commas. What role do they play?

What would be handed to the people making the biros was a blank sheet with stencilled letters and commas in Boetti’s specified font – their job was to fill in the paper but not go over those parts. He liked commas because they suggested movement rather than the stasis of a full stop, a place of pause but where something continues. They indicate the letters to be read from the alphabet above. You go back and forth between the alphabet and the commas, and that spells it out. It’s pretty simple, but the commas seem to float in space, so it’s more difficult than one would think to figure out the phrase. In ‘Mettere al Mondo il Mondo’ they spell out another rule of his that I like to translate as ‘putting the world into the world’ – that the artist takes things that are already in the world, and puts them back into the world. Where Yves Klein invented a particular kind of blue, Boetti just takes the available four colours of biros – he often uses readymade colours. Or he takes phrases, number sequences or office calendars and puts them back in the world.

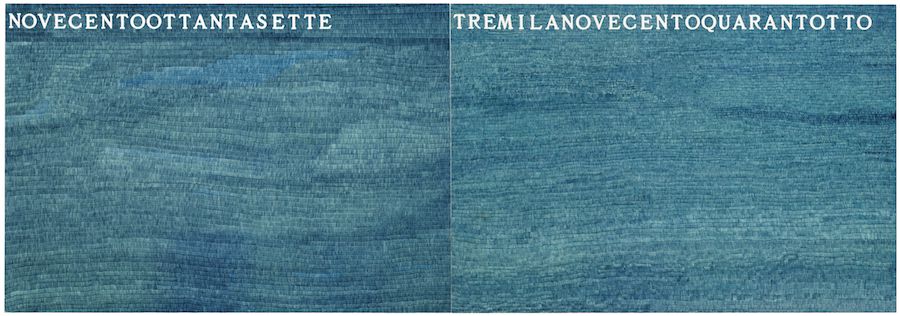

Alighiero Boetti: La Metà e il Doppio, (Half and Double) 1974 – Ballpoint pen on paper in two parts, 70×200 cm

Here he took the number 1974 and divided it in half, so one side reads 987 in Italian. On the other side he doubled it, so that reads 3948. The numbers look random but in the middle of them is the date of the work, so it’s a way of taking something that exists at that point – the year it was made – and putting it back in the world.

Alighiero Boetti: Alternando da Uno a Cento e Vice versa (Alternating from One to a Hundred and Vice Versa), 1993 – Woven fabric 300 x 290 cm.

What’s the logic of these black and white patterns?

There’s an embroidery and a rug which come out of a kind of number game he invented, which is called ‘alternating from one to a hundred and vice versa’. It sounds dry but is actually very playful. He created a grid of 100 squares, with each square itself divided into 100 squares. In the top square you have one black and 99 white squares. In the next square that alternates to two white and 98 black, then three black and 97 white and so on… Once he’d invented this schema, he got other people to plot out the squares, and would make embroideries or rugs from their designs. Of all his schemas, this is probably the most expansive, as there are billions of ways to do it – as for example there are 100 options for where to put the first black square – and so the realisation becomes incredibly open. The chromatic and numeric schema provides an order, and the disorder lies in not knowing how it will be fulfilled.

Alighiero Boetti: installation view. Including two Mappa

The Mappa might well be Boetti’s most famous works…

The idea of the world maps was to fill in the border of each country with the design of its flag. The difficulty was what to do when there was a civil war, and so a dispute about what the flag should be. In those instances – a beautiful idea – he kept the map as a blank, showing that there is a dispute, but undecided. Boetti saw the maps as particularly good examples of his principle of non-intervention. As he put it in 1974: ‘For me the embroidered Map couldn’t be more beautiful. I did nothing for this work, chose nothing myself, in the sense that: the world is shaped as it is, I did not draw it; the flags are what they are, I did not design them. In short, I created absolutely nothing.’

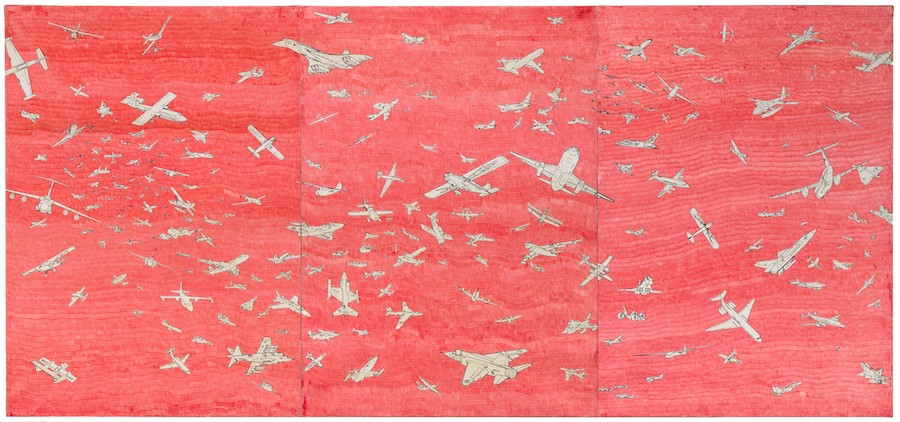

Alighiero Boetti Aerei (Planes), c. 1987 – Ballpoint pen on paper laid down on canvas 3 parts, 139 x 100 cm each

Why was he interested in planes?

Boetti had collected images of aeroplanes whenever they appeared in newspapers and magazines, and had made transfer drawings of them. In 1977 he teamed up with an illustrator called Guido Fuga, who made the composition – a triptych of the sky filled with aeroplanes, all flying in different directions and of various sizes. A lot were to do with the Cold War – they’re mostly American and Russian planes – so you could see it as a romantic image of concord instead of violence. Working with Fuga he made this arrangement – an example of order and disorder because the planes are in complete disorder, but there’s an order in that there are no crashes. Boetti liked Fuga’s drawing so much he photographed it and printed it at different scales, allowing him to make many aeroplane works from small to very large, some with watercolour, some with biro.

Alighiero e Boetti: Regola e Regolarsi is at Ben Brown Fine Arts, 12 & 52 Brook’s Mews London W1K 4DG, and Claridge’s ArtSpace, Brook’s Mews – to 31 August. Images courtesy of Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Callum Innes: Interview of the Month June 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

Over the past four decades, Callum Innes has worked in series, creating luminous abstractions which expose the fundamentals of painting: pigment, surface and space. His tenth show at Frith Street Gallery is the first to include new circular paintings alongside rectangular canvases. The two streams of work are made in the two studios between which Innes divides his time: Tondos on birch ply in his home city of Edinburgh, rectangular canvases in Oslo.

You’re known for the play between addition and removal in your work, in particular for using turpentine to ‘unpaint’ the canvas, leaving only vestigial traces of colour. How does that operate in, for example, ‘Exposed Painting Delft Blue / Violet Red Oxide’, 2019?

I’m reducing and adding repeatedly. What people don’t see is that there been a blue put down first, then a violet, then a red, then a green, then a blue again, and a black over it all, and it’s been gone into several times. The history of all that is there. For example, the black line you see running across horizontally halfway up on one side actually runs all the way across. This is the biggest size I’ve ever worked on – I can still just about go across in one stroke on a platform. If I couldn’t do that, it would be too big. And this work achieves a ‘watercolour effect’, which I’d always found difficult on canvas before. This is also the oldest painting in the show, and one I didn’t see for two years as it was in Edinburgh while I was in Oslo when Covid shut the borders.

‘Exposed Painting Delft Blue / Violet Red Oxide’, 2019 – oil on canvas, 250 x 242 cm Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

You have consistently used black?

Yes, but in the early exposed paintings I would mix all the colours into the black and then reveal the colour. With these recent works I’ve been into the painting maybe five or six times, putting different colours on, exposing that side, drying off, evaporating. There’s much more addition than there used to be.

And the white of the canvas is equally important?

It is. When I have studio guests who are seeing my work for the first time, and they ask ‘how do you paint the white bit at the bottom there?’, then I know it’s working, that there’s spatial ambiguity. I like when the painting spirals from something very simple to something very complex. You don’t know what’s behind what, where’s the foreground. I like that idea of ‘where is space in the painting?’, and how you physically react to it.

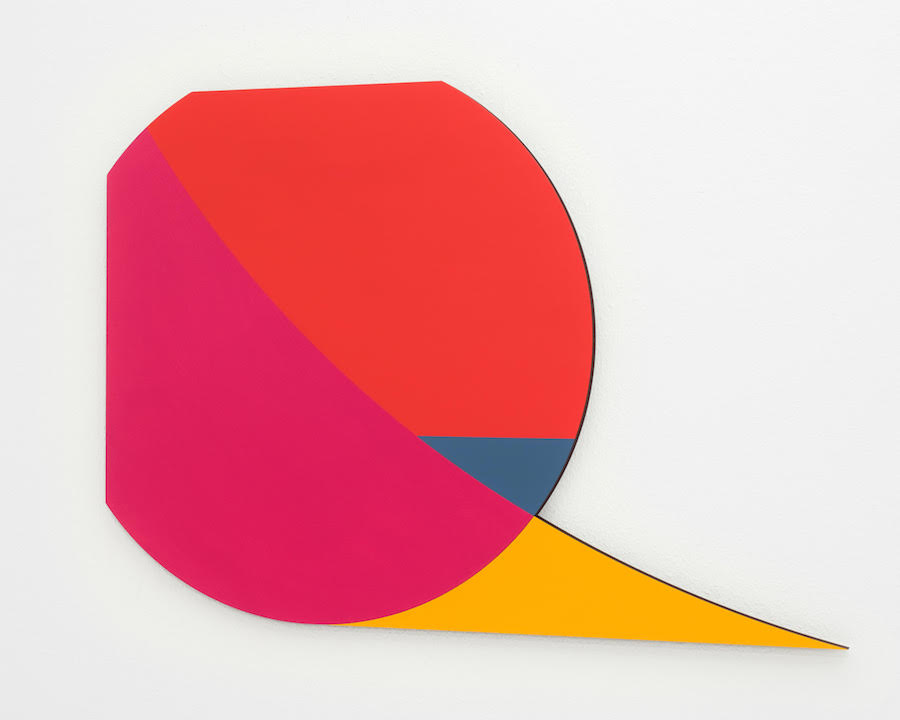

‘Untitled Lamp Black / Deep Purple Dioxazine’, 2023 – Oil on Birch Ply, 180 cm. Photo: Paul Carey-Kent

What led you to the circular format?

The round form originally emerged when painting the end of a whiskey barrel for charity. I really enjoyed working on the hard surface of oak, later birch, and the fact it was wood, so I could see the grain and leave it coming through. After that I thought it would be quite nice to extend it, and to push the work forward through the Tondo.

Why do you make the Tondos in Edinburgh?

Because they’re quite heavy – about 70 kilos each, they’re backed with aluminium to prevent warping – and I have assistants there. I’ve been working on them for about two years, on and off, as I travel back and forward to and from Oslo. There I have a smaller studio and no one really to help me lift things around – so I carry on with the rectangular format on canvas. For me it works really well having two studios. I’ve discovered that it’s very helpful to make something in Edinburgh, not see it for three or four weeks, then come back and see it afresh. My paintings are all about landscape and light, and the studios have very different light: Edinburgh has a very beautiful north top light, Oslo has a hard sidelight – sometimes I have to cover the window to kill the light.

What difference is made by the change of surface?

It changes the physicality of my painting. It’s tough on wood. I knackered my wrist the first few weeks. And it has a very different grip. Canvas sits very comfortably, the birch ply has more physical presence. And they’re heavier metaphorically, as well as physically. I keep the bevel facing out, which expands the painting, so – depending on where you stand – one side can look larger than the other. I found it surprising, the first time I showed one, how physical they are.

‘Exposed Painting Imperial Blue’, 2023 – Oil on Birch Ply, 180 cm. Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Do you hope to generate a spiritual dimension?

That’s for someone else to say. They are about light and landscape, how you look up and see that sky. The research for my practice is actually being outside and walking down the coast or through the countryside. But I won’t title them like that because that shuts it down a wee bit. They’re moments in time.

Do you draw on your walks?

If I’m out I’ll sit down and sketch the landscape, but I haven’t shown them. It something that’s always there. I think by sketching I am absorbing. I’m happiest walking – that’s my pleasure – and the colours are all there in the landscape. Also, every day in Oslo I take these beautiful fold-out books and try to make ten or more abstract drawings before I start, like a musician playing scales, and that’s really helped me. I have over 300 books now, but I’m not sure what I’ll do with them.

Do you have a skill you enjoy other than painting?

I’m an OK cook. I enjoy it, and it’s the same process as mixing paints: a bit of this, a bit of that, you don’t know what you’ll end up with.

Top Photo: Installation view, Callum Innes, Frith Street Gallery,Golden Square. Photo: Ben Westoby, Courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London

Callum Innes is at Frith Street Gallery, 17-18 Golden Square, London to 1 July. You can also see him on the gallery website, talking in his Edinburgh studio.

Sabine Moritz: Interview of the Month May 2023 – Paul Carey-Kent

Sabine Moritz was born in East Germany in 1969: her family managed to move west in 1985, but her early work often took its subjects from recollections of the Soviet era, and she remains engaged in exploring memory and its interpretations. Now she is presenting a series of new paintings across both Pilar Corrias’ London spaces. The gallery state that ‘Under the Skin’ (at Savile Row) and ‘Heart of Drought’ (at Eastcastle Street) focuses on ‘the juxtaposition of the external and internal world, setting the works within a larger continuum of an ever-immediate present… Moritz confronts the viewer with uncertainty, questioning whether memory can ever be an unmediated representation of the past’.

How did you arrive at your abstract style?