Dan Holdsworth: Continuous Topography

26.10.18 - 06.01.19

Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art, Sunderland

As reviewed for the excellent free site Photomonitor

|

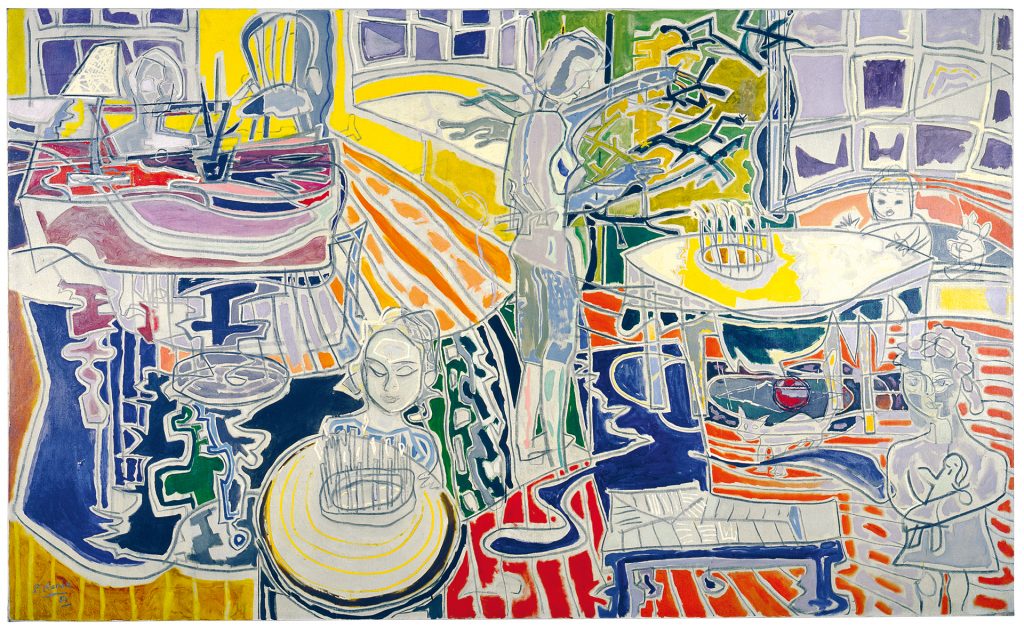

| Screen shot from Continuous Topography |

Dan

Holdsworth’s presentation in the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art

might be described as decidedly simple, yet highly academic.

It’s simple in that there are just two works, with a gallery space each, and they are easily described. Continuous Topography and Traverse

(both 2018, but the outcome of five years’ development) are the first

films made by Holdsworth, who is known for a twenty year photographic

career which has seen him travel widely to capture remote places in an

often sublime meditation on man’s relationship with the environment in

the Anthropocene. Both films present glacial landscapes. In Continuous Topography

we see 11 minutes of what looks like 3D modelling of ice on Mont Blanc,

seen from various angles as the camera tracks around above the scene.

In Traverse, we appear to be flying over an Icelandic glacier

for seven minutes at a steady speed and constant height and angle. That

said, the simplicity is partly brought about by this being just the

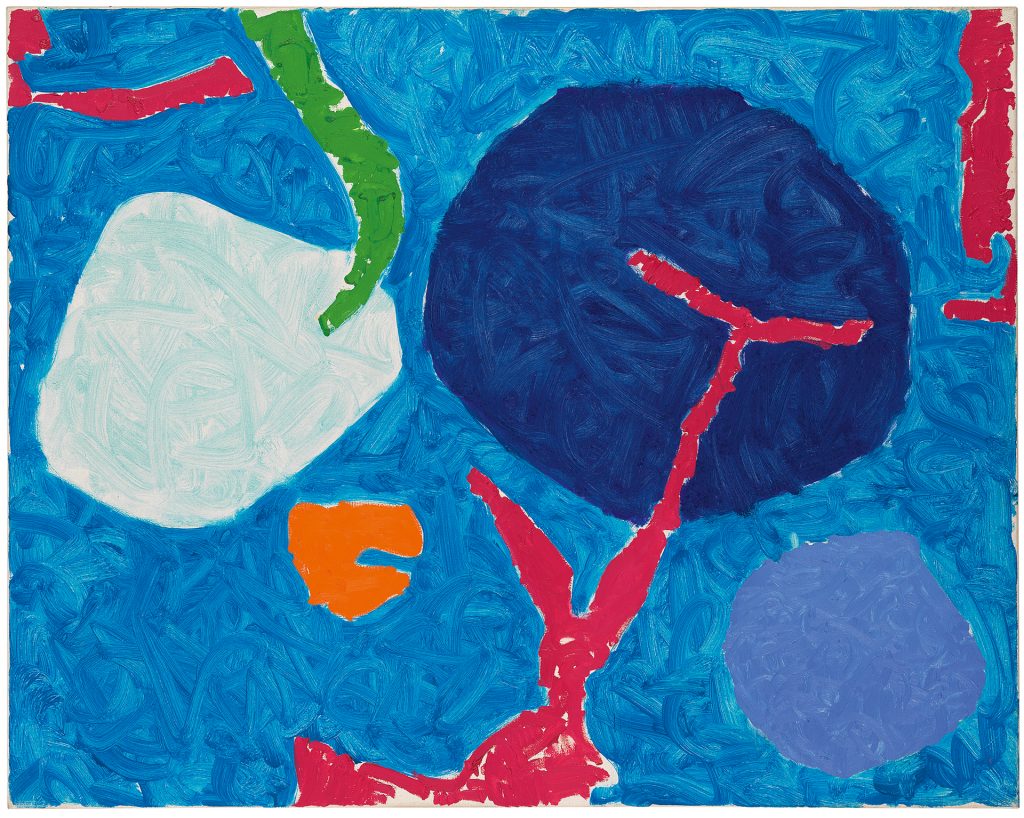

first of two linked solo shows: ‘Spatial Objects’ will run 18 January 17

March 2019 – with 16 sculptural representations of single pixels

marking unique points in space as the ultimate contrast to the grand

aerial views of Part One.

|

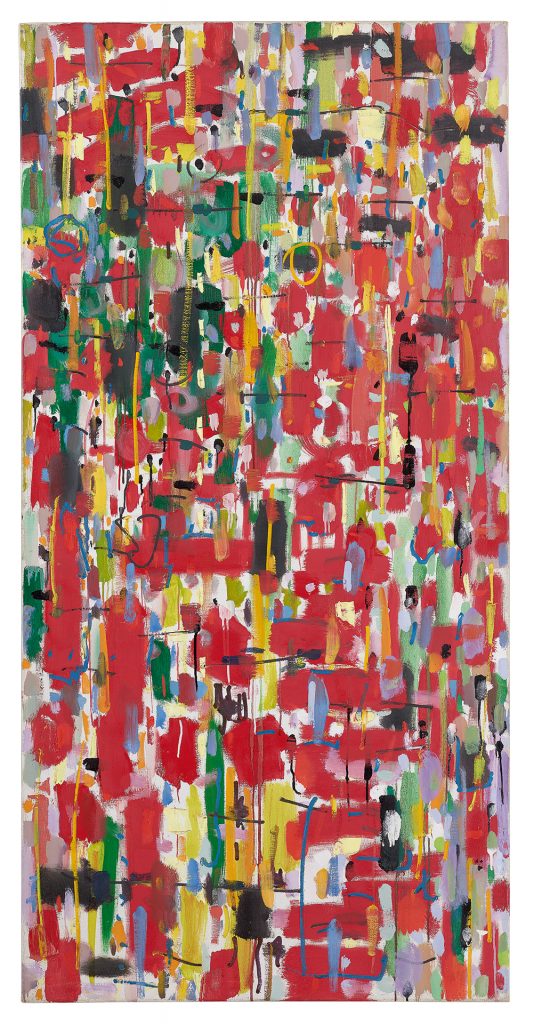

| Installation view: Continuous Topography (one of two screens) |

The background to the films is academic

because it turns out that a lot of research lies behind the techniques

used to capture their startling detail. That is appropriate to the

NGCA’s new home, alongside the National Glass Centre and attached to the

University of Sunderland (which has assisted in marking the show with a

spectacular and learned large format 300 page book which places it in

the context of a critical assessment of Holdsworth’s whole career).

Moreover, Holdsworth – in what is a first for an artist, so far as I

know – has sponsored a PhD student to assist in developing the

techniques used. Mark Allen is a geomorphologist, and the approach he

has helped develop is the latest in ‘photogrammetry’: intense ground

level fieldwork, using thousands of photographs, enables high-end

software to correlate the measurements of each patch of land and model

the site in virtual space. That virtual model is what we see animated in

Continuous Topography.

To call the show ‘academic’,

however, is not to say the experience of watching is dry and

uninvolving. The glaciers of the French Alps prove surprisingly jagged

and dramatic, and though millions of data points are involved in

defining their geography, something of a see-through effect remains, so

that the ice’s shapes look in turn, like moss mottled onto rocks, the

clouds which they literally are (of data) or even smoke. The appearance

is, appropriately, of impermanence. Traverse, too, fits in with

the tradition of the natural sublime. Just as awe-inspiring sights

shown in a way which – even in our image-saturated age – makes us see

afresh, these are striking films.

|

| Screen shot from Continuous Topography |

Nor is the show so simple once probed. The number of issues raised make Part One alone deceptively complex.

It

is easy to assume we are looking at films of landscapes. That would be

the natural result of seeing Holdsworth as pushing forward the tradition

of indexical lens-based representation – a history with which all his

work explicitly engages. In fact, neither film fits. Continuous Topography’s

virtual model isn’t driven by photography as indexical representation

so much as its newer GPS-driven character as a means of mapping exact

times and places. It is, in that way, a highly accurate representation

of reality, but this landscape-as-object doesn’t look as we would

expect. In Holdsworth’s words: ‘I suggest structures through the process

of making the picture, rather than representing them’.

|

| Installation view, Traverse |

Traverse

is also a simulation: a monumental panorama made by digitally stitching

together a huge number of images captured by drone. What we see isn’t

an aerial film, but a film tracking over the digital combination of many

drone-shot photographs. Technically, such a construction might be

compared with Penelope Umbrico’s accumulation of internet-sourced

photographs or Idris Khan’s multiple layering of images rather than

Ansel Adams’ more straightforward engagement with nature.

|

| Detail view, Traverse |

The two

digital journeys across ice are smooth and silent, which also removes us

from the actual experience on the ground. According to Holdsworth, who

has spent days hiking across Alpine and Icelandic glaciers, it is hard

to navigate, given the treacherous surface and the possibility of

treading in hidden crevices, and often noisy due to the ice creaking and

occasionally collapsing explosively. There are also occasional

glitches: Holdsworth points to an interesting difference between

scientists and artists in how they deal with errors: scientists want to

suppress them or explain them away, artists are more likely to welcome

them as a means of exposing the process of construction and place of

making. Both films might be said to visualise what we sense exists, but

could not previously experience visually. They are photography as a type

of scientific investigation. As Holdsworth says: ‘I want to bring a new

world into being, using new means of becoming’. What we have is a 21st century means applied to what – prior to the 21st century – had been widely assumed to be a timeless landscape.

Colour,

light and scale prove hard to pin down. These are colour processes

applied to an essentially monochrome landscapes; Holdsworth very rarely

shoots in daylight, making it hard to assess what kind of light we have

here; and it is difficult to be sure of the magnitude of what we see. Continuous Topography is projected on screens which fill a large room, yet one can imagine that the models could be of microscopic elements. Traverse

is shown on comparatively small TV monitors, reinforcing the

possibility that these scenes might be reduced in scale, but in fact the

strip continually traversed is several hundred metres across.

That

question of scale has resonance. It is impossible to forget, looking at

these landscapes, that they are disappearing rapidly due to global

warming – that the primordial planetary processes they model are now

affected by human activity. Both landscapes are much flatter and less

extensive than they would have been a century back. Holdsworth sees

human history spelt out in that change: ‘The industrial revolution is in

the glaciers’. NGCA director Alistair Robinson sets it out clearly in

his catalogue essay: Holdsworth’s work speaks to the shifting contours

of ice, the vast vistas of pre- and post-historic time and our own

transience, and the fragility of our ecological niche ‘made more

poignant by the state of knowledge we now have about where our

destructive behaviour may be leading’.

Both films are shown twice

on separate screens: starting simultaneously, but running in opposite

directions. That takes some puzzling out, as they seem quite different

until you come to the point at which they match. That double

presentation suggests a cyclical process, taking the viewer into

geological time and putting me in mind of how the Big Bang led to an

expansion which, one theory posits, is set to be reversed in the

enormously long run through the Big Crunch – in which the average

density of the universe is sufficient to halt its expansion and initiate

a contraction back towards its originating state. That would be the end

of the world, were it not that other threats – climate change,

asteroids, the explosion of the sun – are so likely to get there first.

What if you ran the cosmology backwards, I wondered, noticing how this

is a show which takes you to unexpected places…

__________

For further viewing:

|

| Spatial Objects |

Dan Holdsworth’s solo exhibition ‘Continuous Topography’

at the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art continues until 6 January

2019 (to be followed by a second show 18 Jan – 17 March 2019 of

Holdsworth’s ‘Spatial Objects’)