‘Another Fine Mesh’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #160

Alice Cattaneo: ‘Untitled’, 2012

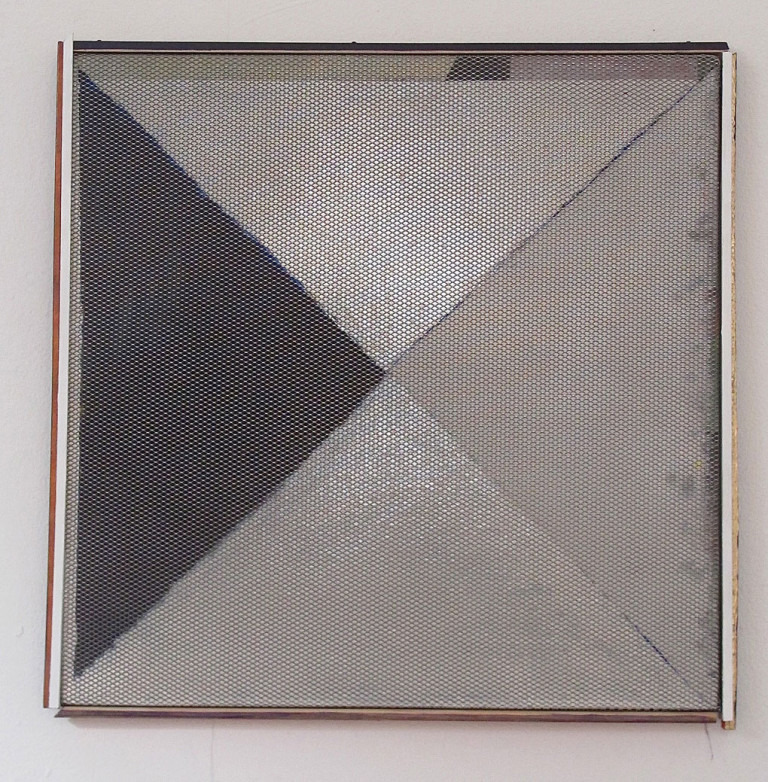

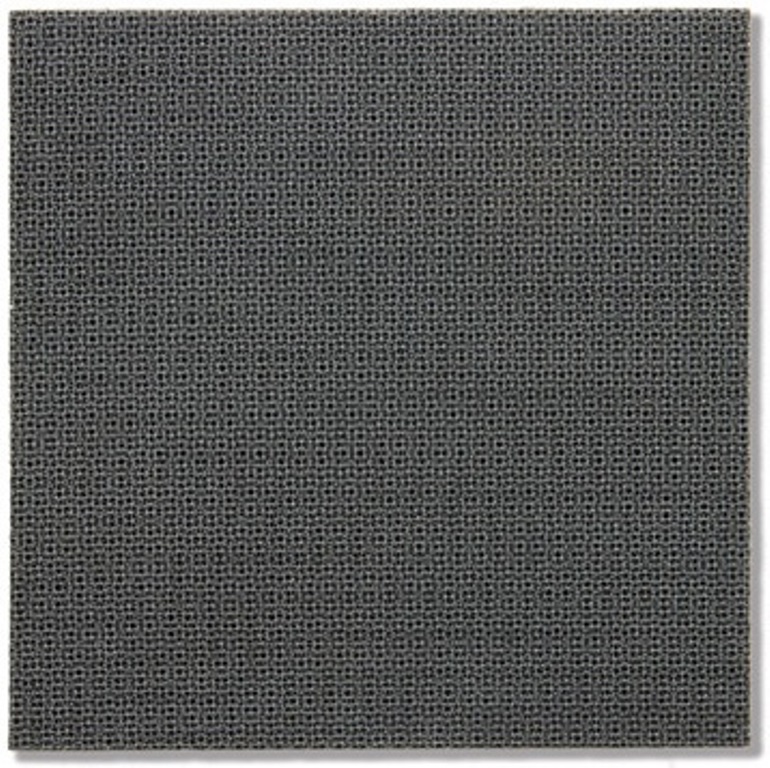

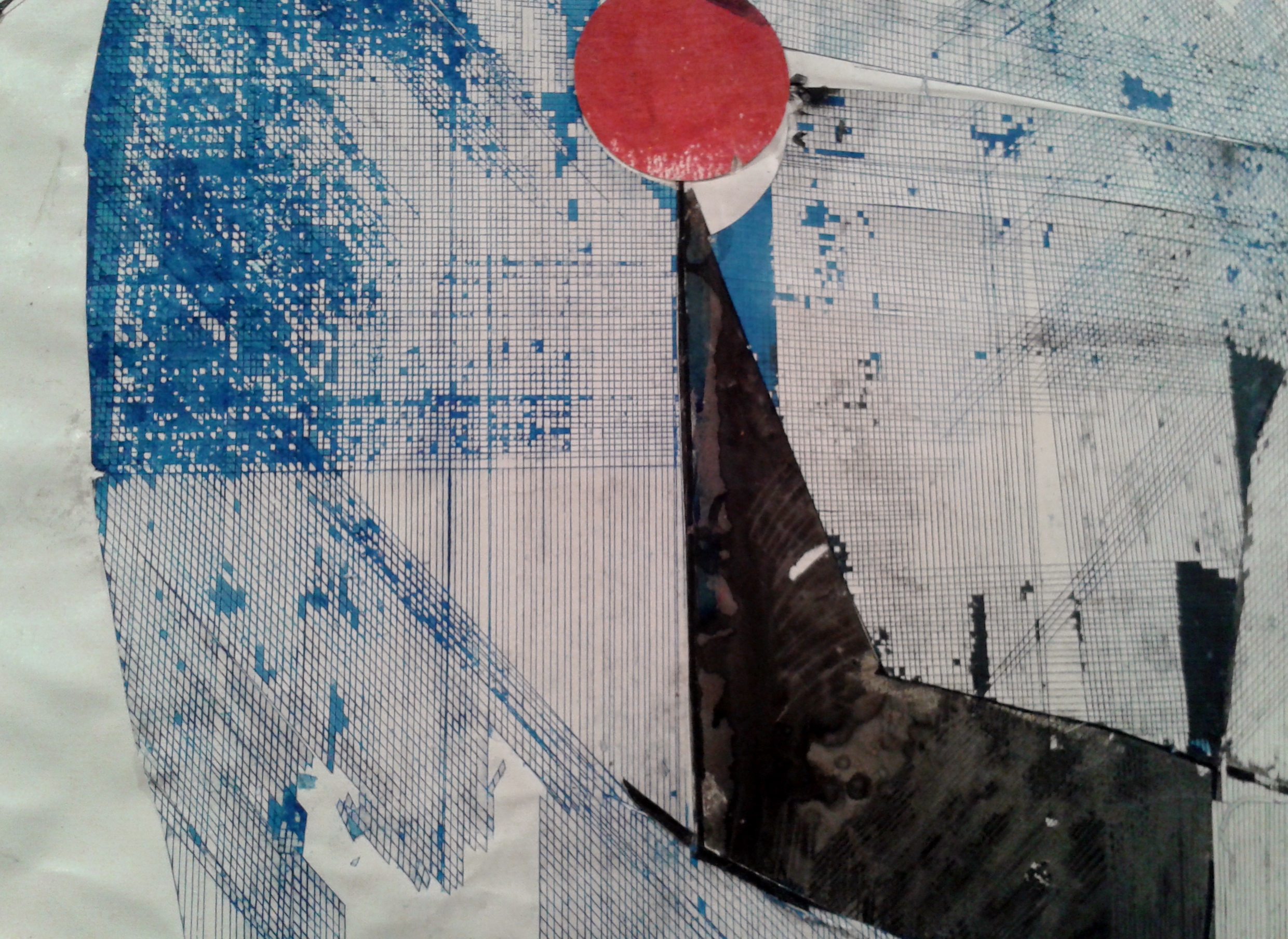

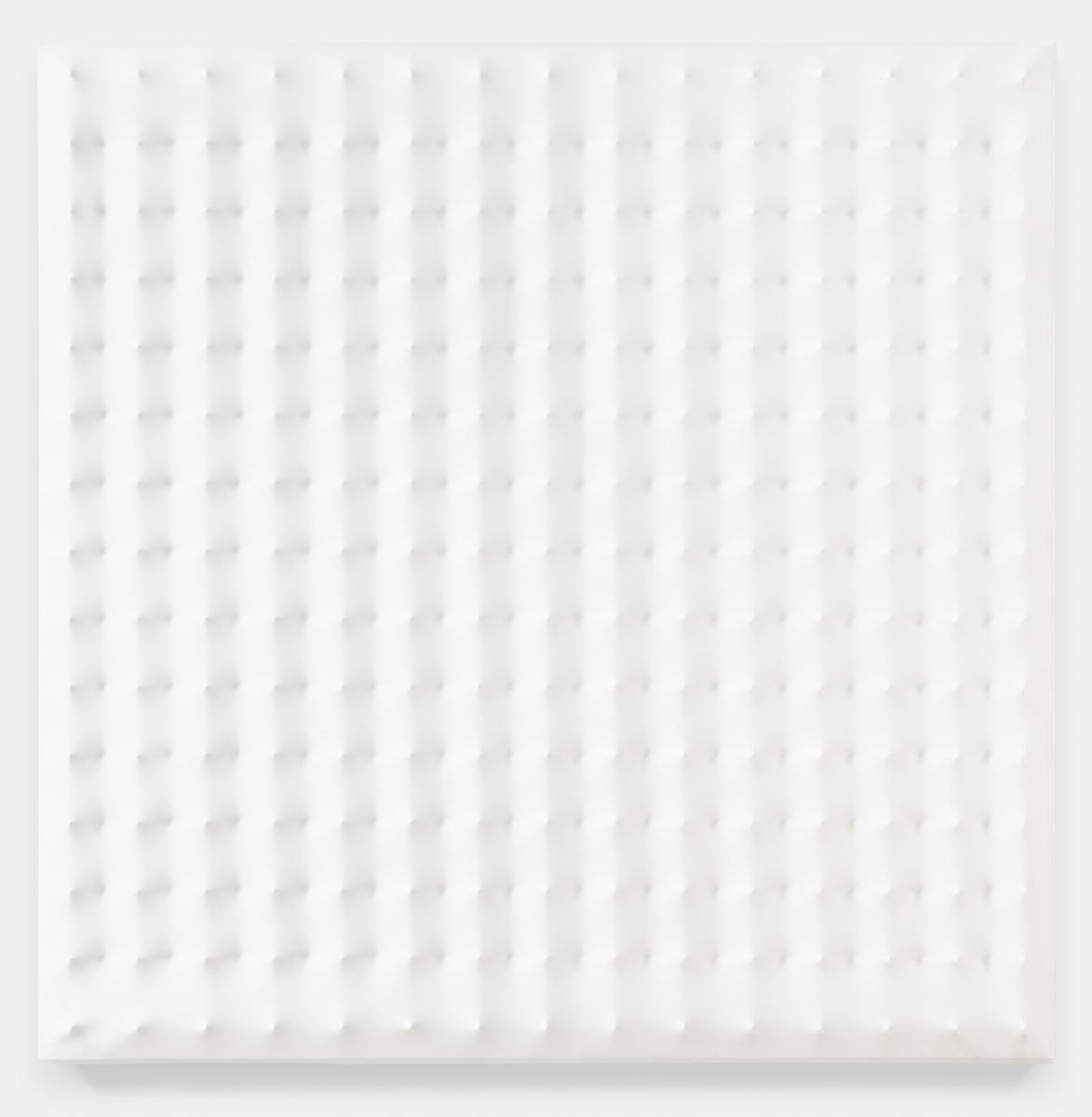

London has enough galleries to make it easy enough to find another show to relate to any given one. All the same, I was surprised to find not just two exhibitions within two hundred meters in which upcoming artists make effective yet contrasting uses of mesh – as form, and as screen; in sculpture and on paintings – but also the great precedent of François Morellet at the Mayor Gallery (the French 90 year old has fine shows there and at Annely Juda). Rosenfeld Porcini (‘lifting the veil’ to 27 May) step into the trendy zone of all-woman shows with 11 choices cohering around a fragile sense of the precious. Italian sculptor Alice Catteneo, who perhaps fits that least, pushes aspects of Anthony Caro and Philip King towards vulnerability: coiled acetate gets trapped under iron; wire mesh intercedes delicately. The combination of differently-weighted materials – which she describes as ‘in between found and looked-for’ – generates a poised tension. TJ Boulting’s new show (‘Encounters’ to 7 May) is solo, yet also rather varied: partly because London-based South African HelenA Pritchard has so many ideas; partly because of the contrast she builds between TJ Boulting’s two spaces. The bigger room is close to white cube, with a few works spaciously distributed: the smaller is packed with a lively interplay of far more paintings, light effects with colour filters, items refracted and several pot plants. The signature material of the many used in her painting-objects is mesh, which covers years-worth of largely unseen layers, evidenced by the still-visible edges of the older applications as the viewer is tempted voyeuristically in, only to be denied full access. Moreover, HelenA (she’s not a Helena, but a Google-disambiguated Helen) uses multiple meshes – black embroidery fabric, net curtain material, a fine steel grid – to divergent effects.

*and Carroll/Fletcher have a very forward-looking group show called ‘Dense Mesh’!

HelenA Pritchard: ‘Square Triangle’, 2006-15

François Morellet’s mesh work ‘3 trames 0º, -22º5, +22º5’, 1971

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘Posing Trumps Sliding’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #159

The intersection of yoga and art is new to me, but Hamburg-based Y8 specialise in the combination, and they’ve come to London to activate the late work of the American artist Channa Horwitz (Raven Row to May 1). While it’s worth visiting anyway to see how Horwitz (1932 – 2013) explored intricate number-driven permutations of geometry and colour which operate on the intoxicating edge of our understanding of their evident systems, there’s also the chance to take part in the activation of the room-sized installation Displacement (2011 / 2016). My wife and I among eight participants – eight being Horvitz’s key number - split into two groups of four. We alternated between adopting set yoga positions and moving around eight black building blocks ranging from 35 to 188 cm high. Both actions demand precision, as the cuboids must be aligned as carefully as possible with an orange grid on the floor. We were encouraged to pause in our shape-shifting to observe the changing scene as the mutating architecture of shapes interacted with the varying positions of the other people. That provided an external focus contrasting with the internal concentration of the yoga. Add the novelty – for me at least – of stretching into tricky positions or finding myself stood on my head, and an hour passed divertingly quickly. Post-performatively, moreover, the drawings which make up most of the show took on a different energy. It made zooming down a Holler seem rather superficial, however long (178m) the ArcelorMittal Orbit slide will be…Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #158: ‘Breasts or Eyes?’

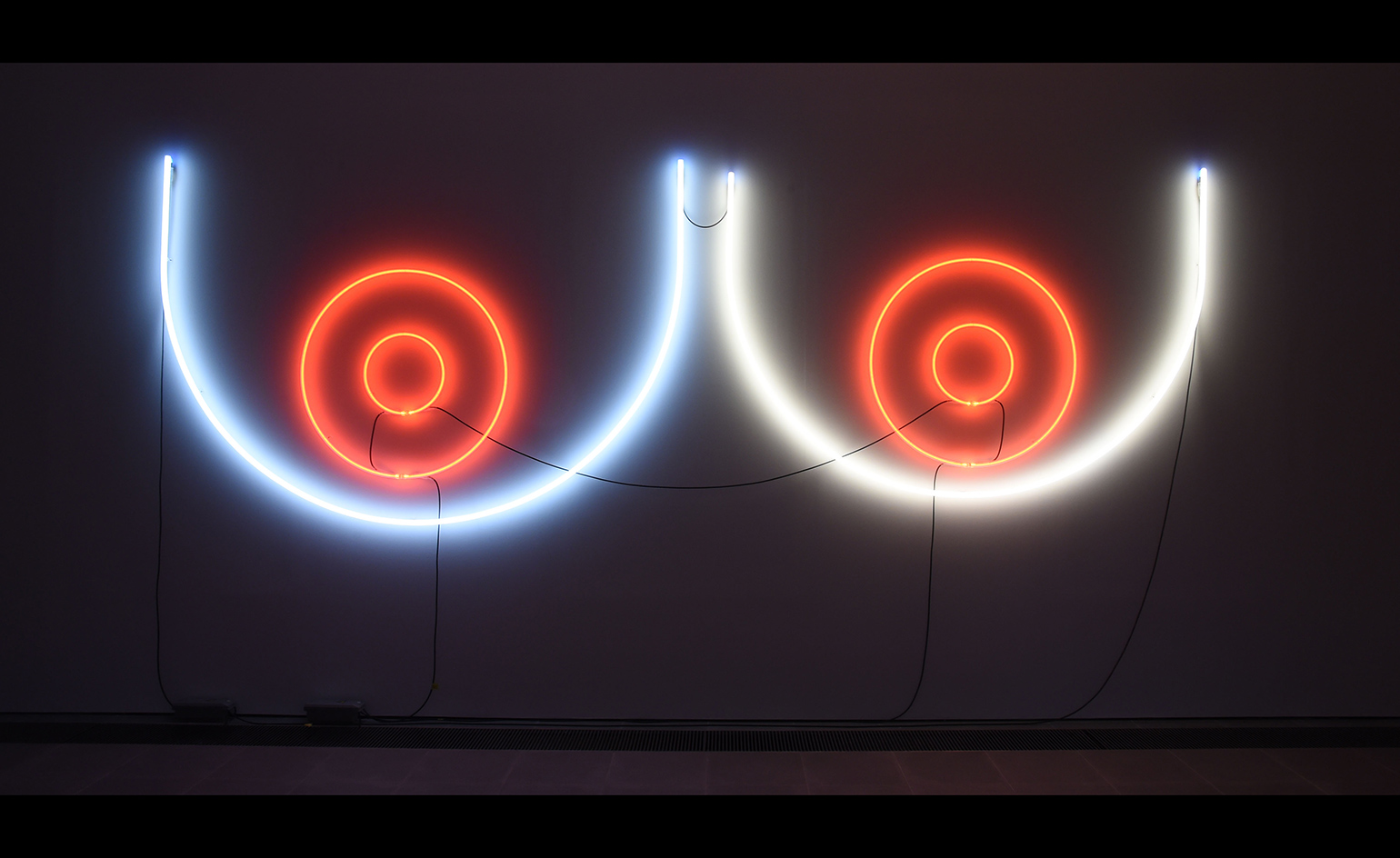

Das Institut installation at the Serpentine Gallery

YOKO, MICHELE, PAULINE, by Sarah Lucas, spread in front of George Jones’ painting ‘THE OPENING OF LONDON BRIDGE’ – photo Julian Simmons

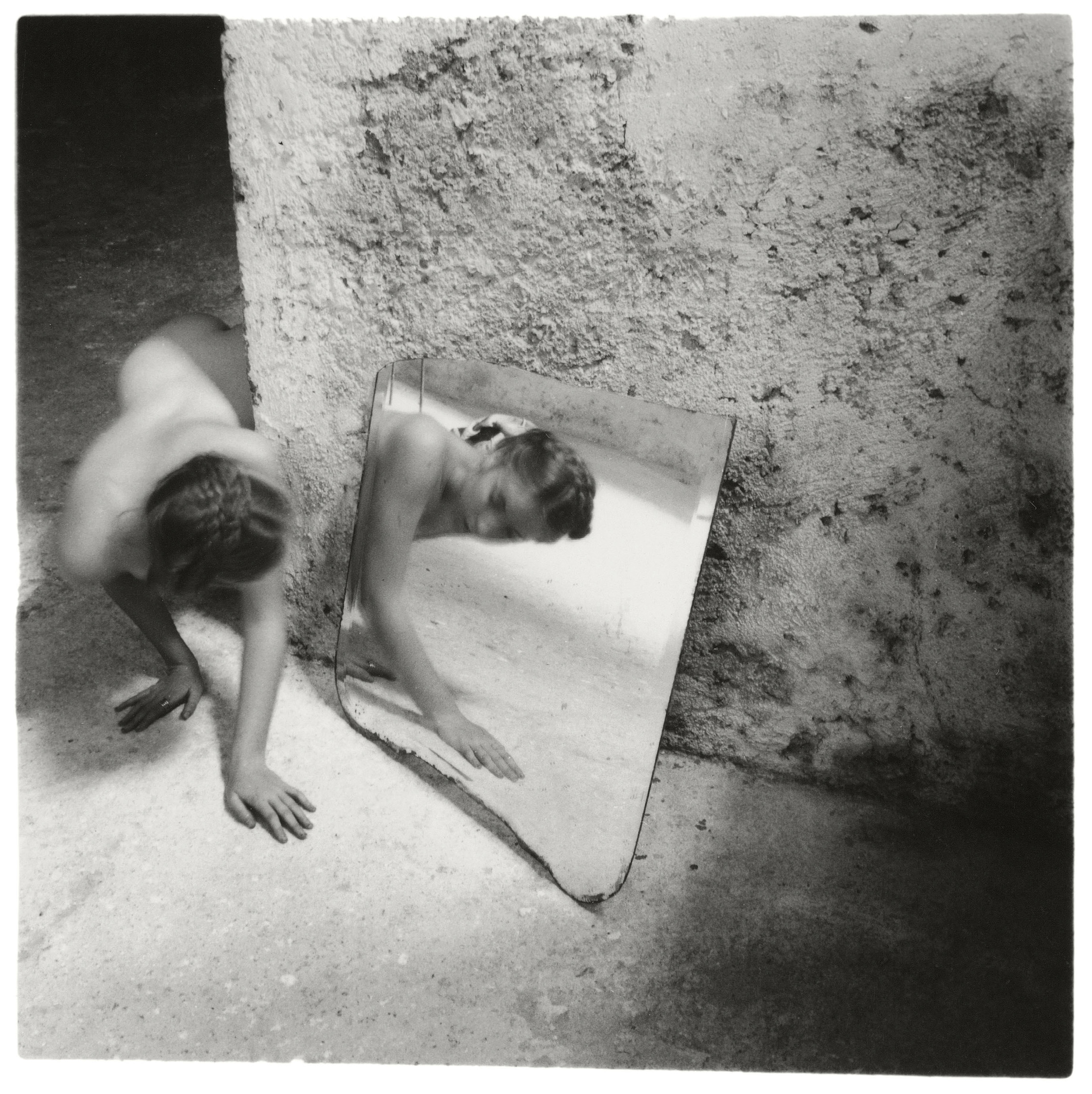

There seem to be a recent convocation on the subject of breasts for

eyes. In December I noted that Julian Simmons’ massive and detailed

graphite drawings of concentric circles (at Lychee One) ‘resemble eyes

and breasts by duck-rabbit turns’, so countering their meditative aspect

with a little bawdy comedy. Simmons attributed his use of the theme to

his partner, Sarah Lucas. ‘Eyes and breasts’, he told me ‘not so

dissimilar …aesthetically, though formally… one takes energy, the other

gives; not entirely, both ways since you enquire’. Lucas herself has

(‘Power in Woman’ to 21 May) brought three literally topless muses back

from their Venice Biennale presentation to the Soane Museum’s yellow

drawing room – the original inspiration for the custard colour scheme of

her British Pavilion. It features plaster casts of the bottom halves of

three women, so no peeping boobs, but Lucas mentions as context how

“Magritte’s painting, ‘Le Voil’, puts a woman’s naked body where her

face ought to be. That is, on the front of her head, tits for eyes.” So I

wasn’t too surprised, by now, to see the biggest work in the

Serpentine’s Das Institut installation (to 15 May) described in the

catalogue thus: ‘the neon breasts which greet the viewer at the entrance

flick on and off, converting the nipples into blinking eyes’. Either

way, both Lucas (rubbing up against Soane’s collection) and Das Institut

(paired with one of their inspirations, the impressively out of time

paintings of Hilma Af Klint) benefit from contexts which alter how we

see things – whether as breasts or as eyes.

Julian Simmons: Orbicular Drawings, 2015

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #157: ‘Lives of the Artists’

Betty Woodman's 'Theatre of the Domestic' at the ICA

It’s an old debate: does the biography of the artist get in the way of the art, or enhance it? Betty Woodman’s ceramic-driven exhibition at the ICA is full of wit and vim, especially when it pitches painting and crockery together to muddle the boundaries between fine art and decoration, and – should the paradox make sense – between real vases and their ceramic depictions. It’s hard not to be more struck by the biographical, though: that she had her first retrospective nine years ago at 76, whereas her photographer daughter Francesca killed herself in 1981 at 22 and is, of course, long since canonical. I drift back to seeing the tremendous ‘On Being an Angel’ at Foam, Amsterdam earlier this year and suspect myself of thinking the wrong thoughts. Maybe these things are better left in the implied biography of the work: the German artist Knop Ferro makes delicate drawings in space out of trembling rods which catch a space somewhere between Alexander Calder and Jesús Rafael Soto – and he seems a most affable man… But an early work in his show at Maddox Arts (‘Gravity’ to 14 May) is of paper slashed with a knife. Suddenly the way those rods slice through the air takes on new undertones, and I start to wonder if the young Ferro was an underground enforcer. Actually he spent the 80’s as a playwright and actor in a Zurich based performance theatre, which makes just as much sense.

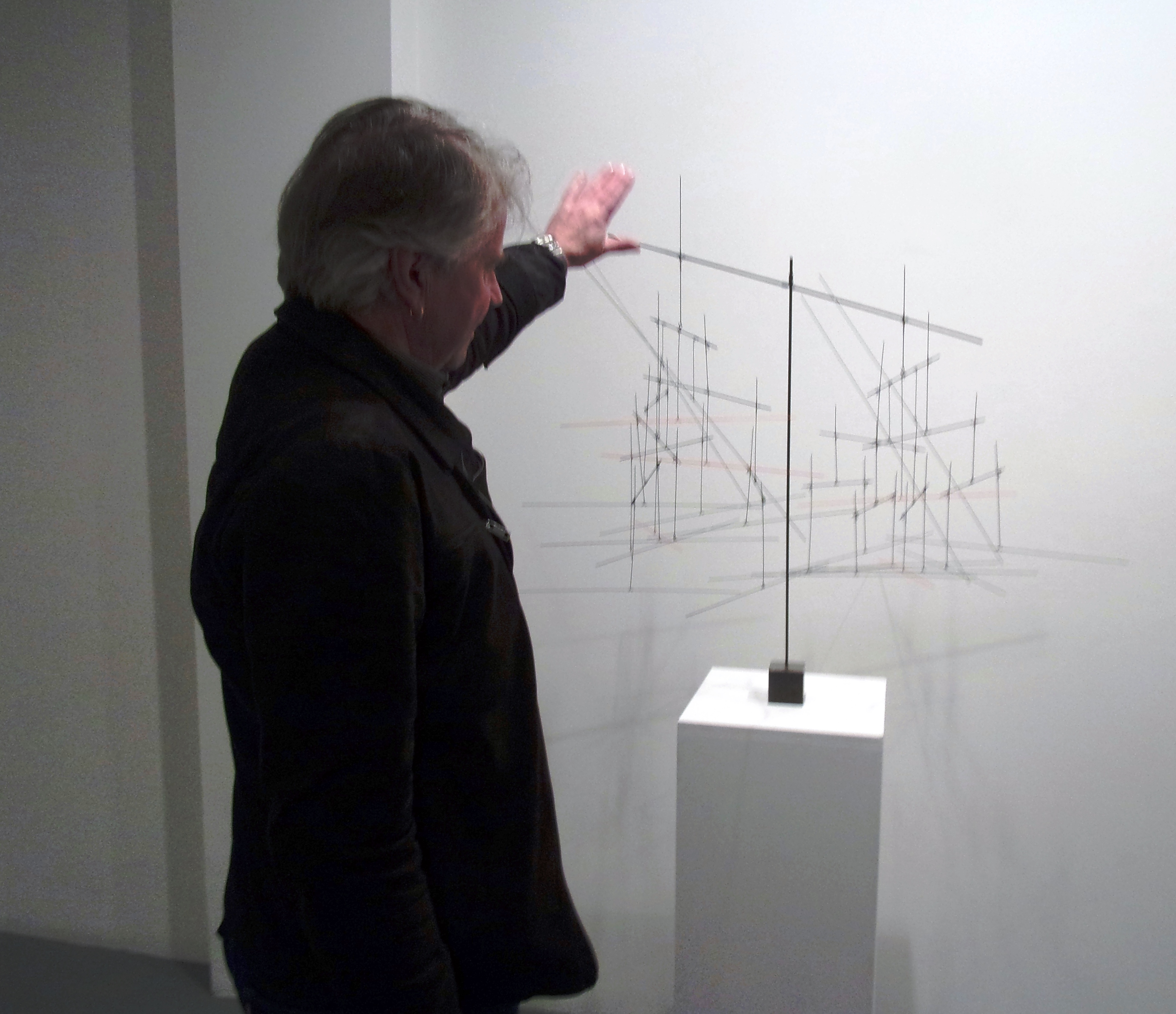

Knopp Ferro: ’20:28′, 2010 – iron

Knop Ferro sets a sculpture in gentle motion, a task he reserves to himself!

Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #156: ‘Education Continues’

It’s always nice when you learn things as a contingent effect of looking at interesting art, and that’s especially so the case of two shows running to 2 April. Steven Claydon’s premise in the brilliantly installed sculpture-and-soundscape ‘The Gilded Bough’ at Sadie Coles is that covering an object can make it more visible. It’s a theory I’ve heard applied to sexy underwear, but Claydon’s more elevated reference and metaphor is scanning electron microscopy, where samples are coated in ultra-thin layers of gold before going under the microscope as “the conductive material increases the quantity of ‘secondary electrons’ that can be detected from their surfaces”. Trend-setting New York collaborative DIS are due to curate this year’s Berlin Biennale and since 2010 have run all sorts of fashion, design, art and commercial collaborations under the general concept of what might be termed a virtual magazine. At Project Native Informant they show three parodies of stock images, such as of ‘the public apology’, ready for the next speech by a shamed politician; and two versions of a family snapshot – one still but moving, as it’s on a sliding screen which covers and uncovers the second: a film of the family which moves but remains in one place. The learning was in first time I’ve watched Winbots at work, ie automatic glass-cleaning devices, which scuttle around on front of the ‘stock’ images as if they can clean content; and in the family’s exaggerated use of contouring make-up, which turns out to have a huge on-line presence which had passed me by completely.

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘Poetry, Art and the Sucking of Cocks’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #155

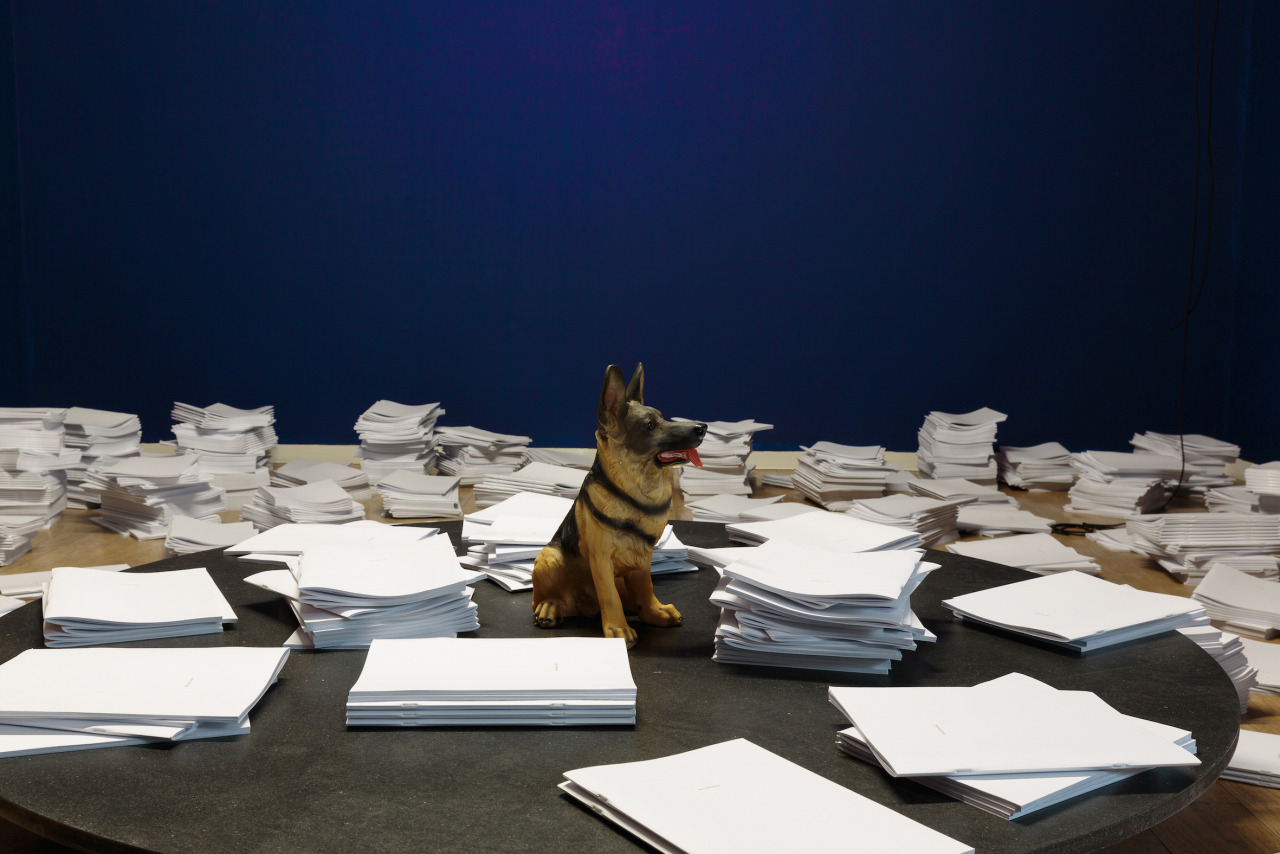

Installation view of Heather Phillipson at the Whitechapel

Visual artists often work with text, but at the moment two are going further by incorporating full blown poetry collections into their shows. For Heather Phillipson at the Whitechapel, it’s her own poetry: she’s been the Whitechapel’s writer in residence, and ‘more flinching’ (to 17 April) is mainly a way to present her new book, a tale of dog love which covers the gallery as its main sculptural element and is free to pick up. I’d recommend you do so, as Phillipson is that rare breed: a visual artist who is also a substantial poet[1]. At Modern Art, sculptor Oscar Tuazon and poet Ariana Reines are very much equal partners in ‘Pubic Space’, a fascinating show (to 9 April) themed around Greek herms[2]. It has three components: a soundtrack of renaissance viol music; tower-like modern herms, mainly of wood and concrete but also incorporating water, candles, and inaccessible books; and the contents of that book, a copy of which you cannot remove but can read at the gallery. It contains not just thirty-odd new poems by Reines, but an assortment of images and appropriated texts which the two Americans have put together, ranging from images of Greek herms to the contemporary priapic. Speaking of which Reines is unconstrained enough to have been asked at one reading[3] ‘Why all the cocksucking?’, her answer being that ‘the abjection and absurdity of relating to a penis that does not belong to one seems like it needs to be taken out of the sphere of the pornographic and reinstated into the kind of hilarity it deserves’.

Installation view of Oscar Tuazon and Ariana Reines at Modern Art

[1] See for example ‘A Is to D What E Is to H’ at

Heather Phillipson – A Is to D What E Is to H from The Wire Magazine on Vimeo.

[2] Herms originate as apotropaic tributes to Hermes, god of transitions and boundaries, and took the form of head, torso and phallus

[3]

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

The Workers: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #154

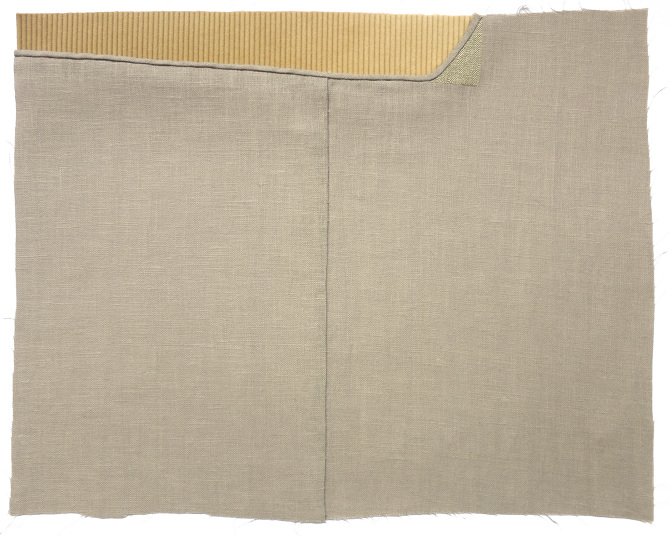

Tamsin Casswell: ‘Plains’ 2015 – linen, cord & hand embroidery 33 x 42 cm

I must have seen over 10,0000 exhibitions, so it wouldn’t be surprising if they’ve covered all the basis categories – and yet this is the first time I’ve come across the seemingly obvious idea of presenting the work of an artist together with that of her team of assistants (Standpoint to 2nd April).

It reminds us that few artists can make ends meet without additional income, often from part-time jobs in the art world such as teacher, technician – or assistant. Add that the artist – Susan Collis – is one of my favourites, and that I knew some of the assistants as interesting artists without realising they have also worked for Collis for several years, and ‘The Workers’ is an attractive proposition. The show generates a shared aesthetic – muted, playing off craft traditions, somewhat inwardly focused. New drawings from Collis – and none of her assisted production – are shown alongside work by Tamsin Casswell, Lucy Clout (whose own show is now at Limoncello), Aileen Harvey, Caitlin Hinshelwood and Kate Morrell – it seems male assistants have never stayed the course. Casswell has the most work – there are seven of her intimately repaired landscape embroideries made out of discarded scraps. Morell’s Warp Set, 2016, arises very directly from her presence in the studio: the photocopy-originated versions of weights from a loom were her elegant counter-proposal to Collis’s tendency to keep drawings flat using any old thing which happened to be around.

Kate Morrell: ‘Warp Set’, 2016

‘The Point of Obsession’ Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #152

Lee Edwards, ‘Opening’ pencil on A4 paper, 30 × 21cm

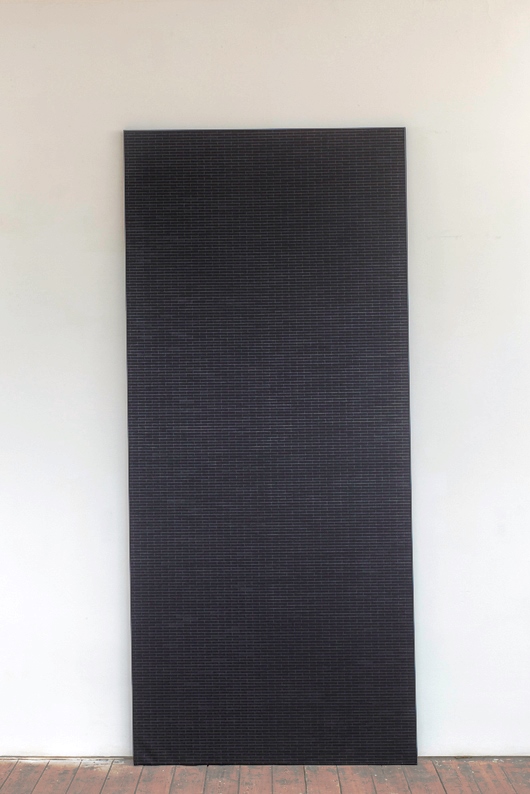

‘I could have done that – and in ten minutes!’, go two popular criticsms of contemporary art. That rather overlooks how easily a famous poet’s work can be copied out, but anyway there’s still plenty of skilled and obsessively labour-intensive art being made. Maria Taniguchi at Ibid (to 2 April) paints the white outline of bricks on a dark grey ground – maybe 3,000 bricks on a typical canvas – then shades most of the bricks black. The eight big paintings at Ibid look the same at first, but the point is how the unblacked patterns provide differing dynamics. She’s building abstraction. Gareth Nyandoro at Tiwani (to 19th March) has an elaborate technique of pasting posters on paper, razoring in hundreds of parallel lines, inking in his image and then ripping off the top surface to reveal only what bled into the slits. The violence makes sense in his geographical context: Zimbabwe. More traditionally, Lee Edwards makes minutely detailed small drawings (‘Fibre of Being’ at Domobaal to 12 March). The subjects are perplexing – used tissues, balled tights, torn knickers – until we realise that they were left behind by his somewhat messy girlfriend when she left him: all that time spent so intensely turns out to be a bravely vulnerable display of pain. Skill and patience in all three cases, yes – but the point in all three cases is – that isn’t the point.

Maria Taniguchi: ‘Untitled’, 2016 – acrylic, canvas, wood support, 274 x 122 cm

Detail of Gareth Nyandoro’s razor technique

‘The Back of Italians’ Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #151:

The back of a Castellani

Will we ever see the back* of Italian art from the 1960’s in London? There’s no sign of it yet, but I can show you the rear of a typical work by Enrico Castellani: the nails, which produce such precise undulations on the front of his paintings, are applied to diagonal cross-planks. Castellani starts from the outside and works in to produce varying rhythms which he says follow unrevealed mathematical principles, but can look dynamically intuitive. Tornabuoni showed a range of less usually coloured canvasses at the last Frieze Masters, but Dominique Lévy’s show sticks to white and silver – favoured by Castellani as the colours (or non-colours?) which make the most of their surroundings. The Superficie bianche include some of the biggest and most complex examples, and are complemented by a paper stack sculpture and more recent, more assertively sculptural, works from the Biangolari and corner-nestling Angolari series. All of which shows more variation than might be expected in how Castellani pushes painting into three dimensions to play off architecture, light and viewer.

*Not that I want to… The latest clutch includes fine displays of Manzoni (at Mazzoleni to 9 April) and Castellani (at Dominique Lévy to 9 April), which opened on the same night, 56 years after they famously formed the gallery Azimut together in Milan; also Alighiero Boetti at Ben Brown, Arnaldo Pomodoro at Tornabuoni, Giacomo Manzù at the Estorick, Angelo Savelli at M&L Fine Art, and Agostino Bonalumi due soon at Cortesi. Phew!

Enrico Castellani: ‘Superficie’, 1974

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.