‘Plurality Please!’ Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #190

|

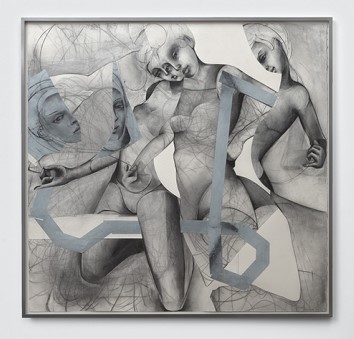

Juliette Mahieux Bartoli : installation with ’Erato Silver’ and 'Eurydice Purple', both 2016 |

Juliette Mahieux Bartoli with ‘Ananke Calliope Coral’, 2016

Perhaps things will change post-Brexit, but there’s a healthy internationalism in the London art scene at present. Franco-Italian Juliette Mahieux Bartoli says her paintings (‘Pax Romana’, shown by Norwegian gallerist Kristin Hjellegjerde in Wandsworth to 21 Dec) reflect the impossibility of cultural singularity in our hybridised world. She should know, having grown up in Washington DC, Paris, Geneva and Rome before studying in London. She arrives at fragmentation of the classical by applying Photoshop to images of herself in performance, which inspire pellucid oils which bring eras together. Mahieux Bartoli also has a rather cunning means of generating titles which – consistent with her internationalism – vary according to the country of display, but the main thing is they look stunning in the (grey) flesh. Evy Jokhova is a notably wide-ranging multi-media artist who also fits the mixed nation model: born in Switzerland to Russian parents, she splits her time between London, Vienna and Tallinn. Jokhova has just taken over the gothic revival Chapel in the distinctive House of St Barnabas in Soho with an installation of three sculptures constructed largely from materials made for their acoustic properties, and drawings of the building’s plans which form the scores to generate music (with James Metcalfe) so that the space can be said to create its own sound (‘Staccato’, presented by Marcelle Joseph Projects, to 4 Jan by appt). I say we want to keep these internationals welcome in London!

Installation shot – Evy Jokhova, ‘Staccato’, 2016 (photo Jan Krejci)

Evy Jokhova in ‘Staccato’ (photo Malcolm Mackenzie)

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘International Smooth’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #189

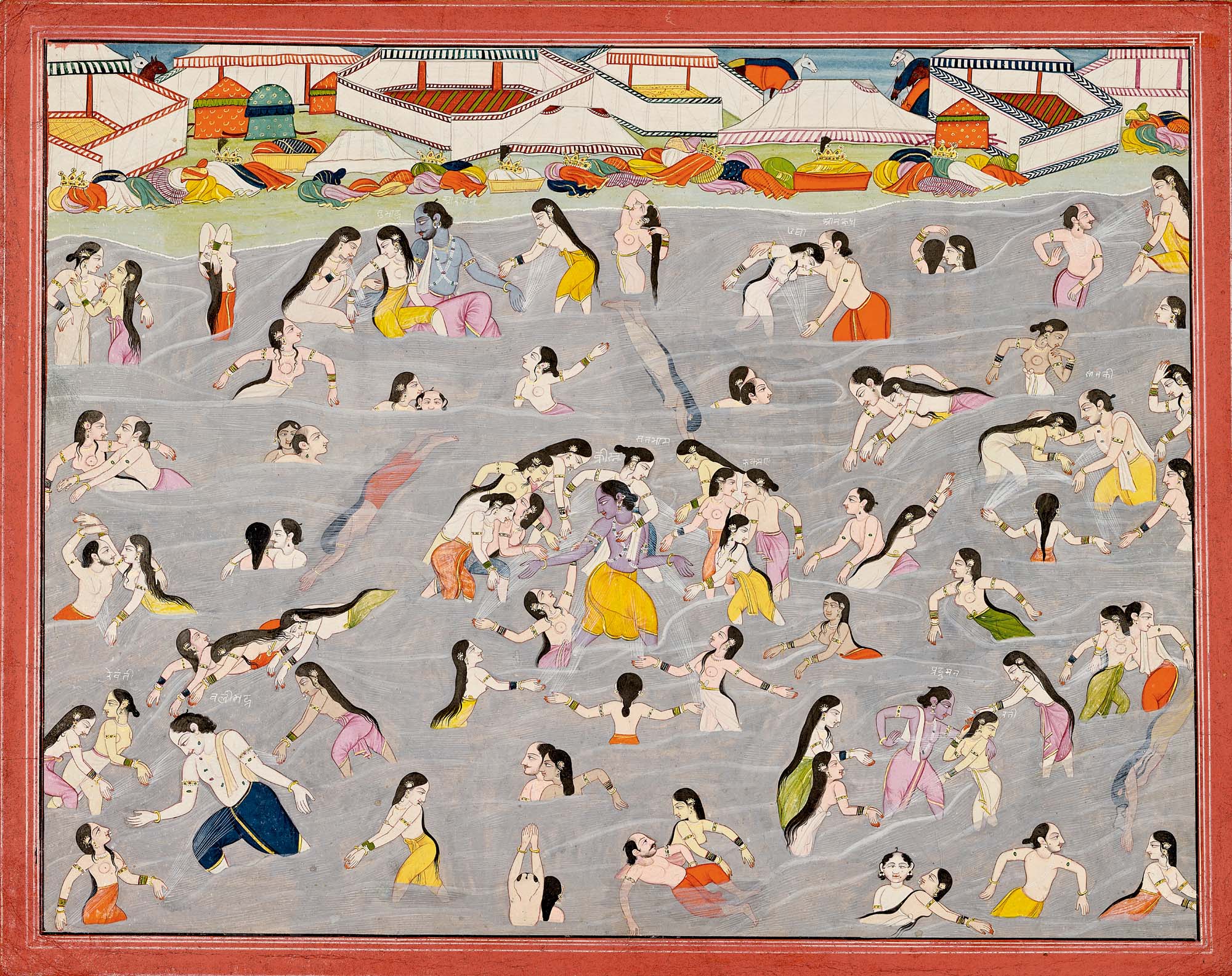

‘Krishna and his Kin dallying with their Wives and Courtesans by the Sea Shore at Pindaraka’, c. 1810-20

It shows the richness of London’s gallery scene that you can – as always, it seems – see easy as you like an impressive selection of late 20th century Italian art (at Cortesi, Thomas Dane, Luxembourg & Dayan, Mazzoleni, M&L, Partners & Mucciaccia, Robilant + Voena and Tornabuoni) and also, during this ‘Asian Art Week’, a wide-ranging survey of a different market sector. The exquisite selection of Indian miniatures at Francesca Galloway (to 11 Nov) includes ‘Krishna and his Kin dallying with their Wives and Courtesans by the Sea Shore at Pindaraka’ – which I definitely love for its intricately energetic organisation of shape and colour; lively sense of movement, including the underwater figures; and possibly also I suppose out of some fellow feeling for the life of the princes shown, who seem to have things pretty easy. The abstract-looking cloud paintings of Jiang Dahai at the Mayor Gallery (‘Diffusion’ to 17 Dec) aren’t such a contrast as might appear, as there are many colours (in up to 15 layers) applied by a spray-fine brush-speckling technique you can see at www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/2014-11/19/content_18943545.htm. He’s one of many Chinese artists who’ve settled in France after going there to train traditionally, only to turn their knowledge to other ends. Wang Keping is another, but I was unable to see his distinctive wood carvings at the Aktis Gallery as advertised due to a three hour closure to prepare what must have been a rather elaborate event. Ah well, we wouldn’t want it too easy…

Jiang Dahai: ‘Harmony’, 2016

One Work: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #188

Robert Therrien: No title (pitcher with yellow spout)’, 1990

Enough of exhibition reviews, I’ll look at just the one work this week *. LA artist Robert Therrien is best known for playing with fabricated scale so that, for example, saucepans tower above us, recharging our inner child’s sense of everyday wonder (and daftness: are the cooking utensils ‘awe-dinnery’!?). Parasol unit, though, concentrates (‘Robert Therrien: Works 1975-1995’, to 11 Dec) on earlier handmade works, which seek related effects by different means. Take this deep and shaped wall-mounted construction of enamel and wood. Is it a sculpture, or (punningly) a picture of a pitcher? Or even of a bird with a yellow beak, simplified a la Brancusi? Therrien likes to give solid form to the unstable or impermanent (snowmen, for example, or clouds, including one which is fitted with taps). That triggers our awareness of the pitcher’s function as predicated on instability, for it stands ready to be tipped, to pour like a cloud. All of which makes it sound somewhat comical, when actually my first impression was of a combination of triangles driven by abstract concerns, balancing large white against small yellow, playing off area and intensity. And later I fixed on it as an archetypal jug with some of Morandi’s reverence for such items, inscribed in how carefully approximate it is in the making. From gnomic to comic to platonic, a simple form proves hauntingly complex.

* hats off to the Afterall series of whole books which focus on one work

Robert Therrien: installation view showing ‘No Title (cloud with faucets)’, 1991

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘No Need to be Trendy’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #187

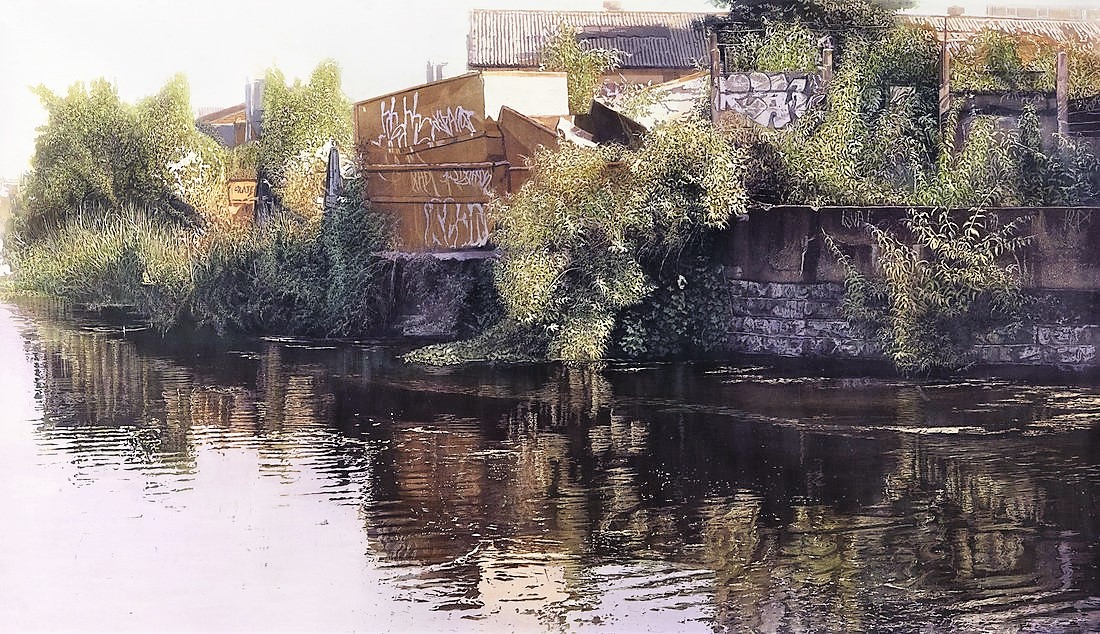

Juliette Losq: ‘Lethe’, 2016 – Watercolour & ink on paper, 100 x 174 cm

Not every interesting show is at a ‘hot’ gallery. The current shows at Waterhouse & Dodd, better known for their secondary market activity, and Long & Ryle, who have a somewhat conservative roster, are cases in point. The former has Juliette Losq’s technically impressive watercolours (‘Terra Infirma’ to 12 Nov). Losq finds a modern space for the picturesque in London’s zones of marginal nature, somewhere between the romantic sublime and its modern corruption. The latter is often represented by graffiti made painterly, though in the most radical piece it’s the patterns of pylons which appear on the side of a cabinet rendered function-free by plywood paintings cascading like tongued vegetation from the drawers.

At Long & Ryle David Wightman’s apparent subject (‘Empire’ to 11 Nov) is imagined mountains by lakes, which he collages out of shapes cut from textured wallpaper. The textures, which Wightman paints over in acrylic, can be read as geological strata or rippling waves. Are the paintings bland substitutes for the wallpaper they incorporate? Wightman sets up the possibility in order to refute it: his colours are intrusively improbable as decorative schemes and more suggestive of pollution than of nature. Celestine iv sets an ice cream mountain against a sulphurous pool and an ink-dense sky. Joseph Albers and Michael Craig Martin come to mind as we see how the same landscape template can be varied by changing both colour and textured pattern. It turns out that the paintings are, primarily, abstractly-motivated experiments with a language.

David Wightman: ‘Celestine iv’, 2016 – acrylic and collaged wallpaper on canvas, 70 x 105 cm

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘Where Are They Now?’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #186

Why must people get in the way when I’m photographing paintings? Ah, I see it is Alice Browne herself, I guess that’s OK

Why must people get in the way when I’m photographing paintings? Ah, I see it is Alice Browne herself, I guess that’s OK

You have to stay alert to find the galleries at this time of year: several reopened in new premises ahead of Frieze. Limoncello is onto its fourth permanent space – the biggest yet, and though the address – Unit 5, Huntingdon Industrial Estate – sounds forbiddingly off-track, the gallery’s is the first door you come to if you walk north from Shoreditch High Street Station. It has reopened with Alice Browne’s big Dante-inspired paintings (‘Forecast’ to 5 Nov – see also http://fadmagazine.com/2016/10/05/225376/), which features abstract-looking views of the never-finished chaos of hell alongside paintings of futurologists whose heads are turned back to front so that, in Dante’s account of their tortures, ‘tears coming from the eyes / Roll down into the crack of the buttocks’.

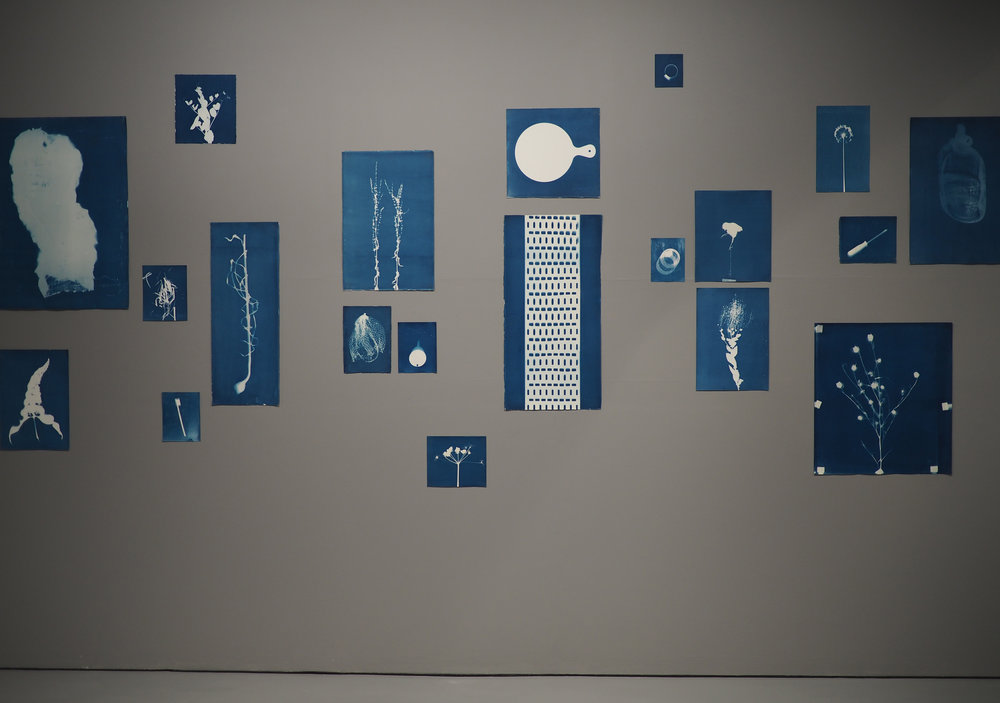

Dalla Rosa, formerly in Clerkenwell, is now in Chalk Farm, where Jessie Brennan’s socially engaged account of a community garden in Peterborough, told through testimony and cyanotypes (including a rather touching dead robin), also makes for a strong opening (‘If This Were To Be Lost’, 3 Leighton Place to 29 Oct).

Skarstedt (8 Bennet St) is only 200 yards from its former location, but has more room for one of the best shows in London, pairing David Salle and Cindy Sherman as if that were always meant to be.

Cabinet, after what seems (and probably is) years of building, have migrated from Clerkenwell to Vauxhall; Andor from Hackney to London Fields; Purdy Hicks from Bankside to Kensington; and Project Native Informant from Mayfair to Holborn Viaduct. And I dare say there are others…

Jessie Brennan installation at dalla Rosa

‘Super-late-ive’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #185

Dorothea Tanning: ‘Victrola floribunda’, 1997

Proof, perhaps, that that being an artist isn’t a proper job is that you don’t normally get to retire. There’s plenty of evidence in London now. Georgia O’Keeffe (Tate Modern to 30 Oct) lived to 98, and lots of her best work was late. The show opposes the interpretation that her flower paintings are sexual – a line started by her husband Alfred Stieglitz, but denied by her. Fair enough, but it seemed to me that – whether O’Keefe meant it or not – the whole show had a sexual aspect,, what with fleshy mountains, views through pelvises, folds and openings everywhere… Flowers were the least of it… But in the case of Dorothea Tanning’s production from her late eighties (which was recently at Alison Jacques) flowers are all you get: big, lush, not unsexy, imaginary. They’re superlative, and enhanced by Tanning asking poets to name her invented blossoms and write a matching verse*. Come to that 76 year old Araki (Hamiltons to 27 Nov) is quite clear about his flower photos standing in for genitalia. But all those florists are trumped by the late-blooming Japanese-Brazilian Tomie Ohtake at White Rainbow (to 12 Nov): most of the show was made in her last year, ie after turning 100!

Nobuyoshi Araki: ‘Flowers’, 2007

* For example Victrola floribunda by John Ashbery

I am always shaking deliquescent bonbons

out of my hat. Is that a hat-trick?

I have never known what “hat-trick” means,

though I am sure there are many who do

and many more who do not.

‘250 heads are better than 1’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #184

Paloma Varga Weiz: ‘Dreigesichtfrau’, 2005

Frieze week is busy enough – see my choices at paulsartworld.blogspot.co.uk – to make me wonder whether a fulltime job is such a good idea. Maybe the answer would be the multiple self – think how many Rachel Macleans there are in her films, that would be handy. Certainly one head seems unduly restrictive, and as it happens Shezad Dawood’s show at Timothy Taylor (to 22 Oct) includes a double-sided head among its impressive virtual reality effects. Not so far away, though, in the Phillips auction exhibition, I came across a three-faced woman in glazed plaster by Paloma Varga Weiz (estimate £8-12,000 if you have your bidding head on). Then came five-heads at MDC. The highest impact figures in Matthew Monahan’s alluringly sinister 2 and 3D de- and re-constructions of the classical (‘Shut-ins and Shootouts’ to 12 Nov) are faces shot through from the back and sculptures half-hidden in dark mesh boxes. But I also liked the mysteriously titled drawing ‘Tera Flop Club’. Now, I thought, we’re getting somewhere. The Lisson Gallery felt like arrival. Tony Cragg’s extensive new show (to 5 Nov upstairs and down in both the Bell Street spaces, and outside!) includes the rather atypical ‘We’. This bronze cone incorporates, in whole or in part, around 250 cragg-heads. Ideal: that’s pretty much one self for each exhibition which can be visited in London this week.

Matthew Monahan: ‘Tara Flop Club’, 2016

Tony Cragg, Installation view at Lisson Gallery (27 Bell Street), London, 1 October – 5 November 2016

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘After the Binge’: Paul’s Art Stuff on a Train #183

I was surprised to hear from Professor Anita Taylor, Director of the Jerwood Drawing Prize, how the three strong panel of judges* chose the 61 drawings included in the 22nd prize exhibition (Jerwood Space London to 23 Oct**, then touring to Bath, Leigh and Poole). All 2,537 entries were gathered for physical inspection of the original in a two day binge, no pre-sifting, no jpegs. Then, not only were the judges not told the names of the artists, they weren’t given titles, nor any statements about the work – so the focus was very purely on the drawing. They did well, then, to light on quite a few interesting processes and subjects which I’m not sure I’d have worked out without the helpful summaries written subsequently for the catalogue. Would I have deduced that my favourite work here – Nathan Antony’s video ‘Black Friday’ – was made by applying a hair dryer to the thermally sensitive surface of a till receipt, then letting it unroll naturally? That Julia Hutton’s subtle lines were made by burning as the sun streamed through her studio window? Would I have guessed that the figures-come totems in Michael Hancock’s ‘Allotment 3’ are decayed Brussels sprout roots? The £8,000 first prize was awarded to another filmed process, Solveig Settemsdal’s ‘Singularity’, nine minutes following white ink suspended in cubes of gelatine.

* Artist Glenn Brown and museum directors Paul Hobson and Stephanie Buck

** The London venue has the bonus of Jasmine Johnson’s installation bringing African wildlife into the café courtesy of the world’s largest collection of game shot by one man, which turns out to be at the Powell-Cotton Museum in Kent.

Most days art Critic Paul Carey-Kent spends hours on the train, traveling between his home in Southampton and his day job in London. Could he, we asked, jot down whatever came into his head?

‘Near-Death Experience’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #182

Gretchen Faust: Installation view of ‘Aint Wet Paint’

Corvi-Mora and Greengrassi are unusual – possibly even unique – in sharing a building and swapping, from show to show. between its large lower and smaller upper spaces. The current pairing works well. Upstairs is Gretchen Faust (Greengrassi to 8 Oct), possibly the only German-sounding American artist who teaches yoga in Devon. An introductory joke – unopened puzzles posited as art unless the purchaser unseals them, when they revert to puzzle status – leads in to a wall of 5,000 hyper-delicate doilies. Cut from gold-sprayed tissue paper, they flutter under breath. It was meditatively therapeutic work, said Faust. They’re all different but ‘if anyone mentions snowflakes’ she went on devilishly, just after I’d mentioned snowflakes, ‘I have to kill them’. Diverting Fuast by asking where her text’s words come from – St Francis of Assisi – I lived to tell the tale. Downstairs is Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s set of paintings ‘Sorrow for a Cipher’, an array of eight men, seven lolling on large linen grounds, and just the smallest standing more assertively on canvas. Yiadom-Boakye’s explained that although she’s known for completing pantings on a single fresh day, that applies only to work on canvas. Linen’s more absorptive properties suit the process spreading out longer. So she seems to be moving in a slower direction here, except that the quickness of a canary perched on a hand on linen was the highlight. Greengrassi / Corvi-Mora supply rather good soup at their openings: add the stimulating art, and my visit was more sustaining than fatal in the end.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye installation view

‘Beauty Beyond the Name’: Paul’s ART STUFF ON A TRAIN #181

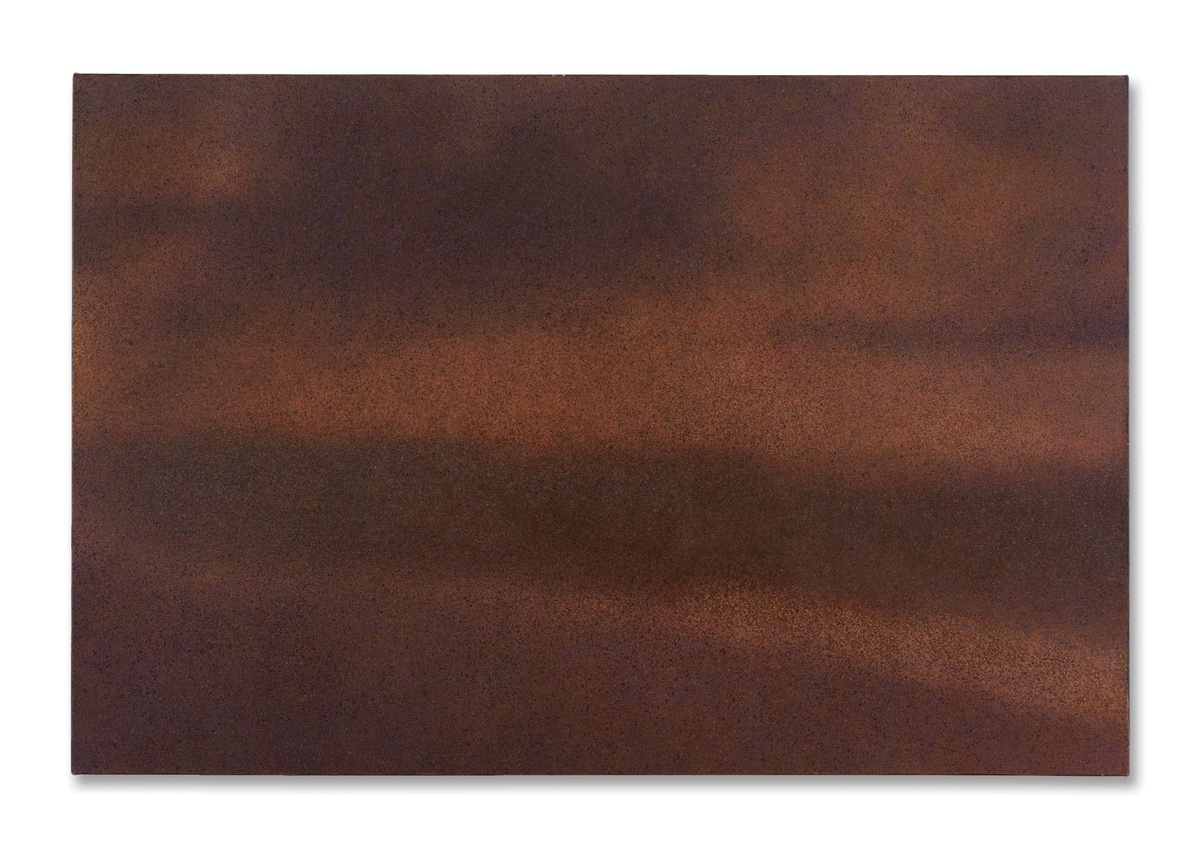

Yun Hyong-keun: ‘Burnt Umber & Ultramarine Blue’, 1992

Are you a namist? I only ask because I’m pretty sure I can be. Dash Snow, Zipora Fried, Jack Strange – I immediately want to know what lies behind such names. David Smith, Sarah Jones, Ralph Brown – the urge, quite unfairly, diminishes. And for Anglophones the problem increases with foreign names. Koreans, for example, can all sound confusingly similar to the western ear. Cho Yong-ik, Chung Chang-Sup, Chung Sang-Hwa, Kwon Young-woo, Lee Dong Youb and Yun Hyong-keun are luminaries of the Korean school of Dansaekhwa, but if you’d asked me to name Korean abstractionists a month ago I might only have come up with Lee Ufan and Park Seobo. That partly because Ufan (who’s represented by Pace and Lisson and better known for his connections to the Japanese Mono-ha group) and Seobo (recently featured at White Cube) have shown the most widely. Whether or not that reflects the comparative merits of their works, I suspect their relatively memorable names play a role too. Anyway, even if slowed by namism, Dansaekhwa (literally, ‘monochrome painting’) has been picking up interest lately, and Yun Hyong-keun now has his first London solo show at Simon Lee. His mature style is narrow but intense: water and dirt are invoked through washes of ultramarine blue and burnt umber which combine to form a glowering near-black and bleed out at the edge of geometric forms, generating a trembling beauty due to the differential absorption of the various layers of thinned paint.

Yun Hyong-keun installation view at Simon Lee

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.